A conversation with painter Linda Alice Dewey and poet Anne-Marie Oomen about their collaborative project On The Precipice, a small exhibition of four paintings and four companion poems on display in the Glen Arbor Arts Center’s Lobby Gallery [April 29 – August 11, 2022]. The GAAC’s exhibition, and this conversation, is an exploration of how artists collaborate, and the tradition of ekphrasis – the practice of creating a literary description of a work of art.

Category: Creativity Q+A

Creativity Q+A with Michelle Tock York

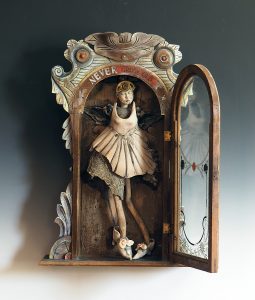

Michelle Tock York, 60, is a sculptor working in clay, and with a wide range of intriguing found objects — from organic finds [e.g. driftwood gleaned from the beach] to trinkets and forgotten objects scavenged from antique stores and other treasure troves. Her goal? To turn all these disparate materials into “cohesive” works that tell the stories this Traverse City artists wants to tell. This interview took place in March 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity.

You work with clay in a sculptural way.

I do have a potter’s wheel … but I’m definitely not a potter. I love hand building. I had to know [wheel] pottery well enough to teach it at the high school level [1]. I taught the [college level placement] classes.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

I love the push and pull of the clay. I was a print maker in college. I loved manipulating the [printing] plates; but it’s the actual touching the clay that’s exciting to me. I love creating something out of a blob of dirt. As a child, my parents loved antiques. They would drag me to every antique store, and I began to love the found objects, the cool old toys that I’d find in there, wood that had a patina and a history … That where the found objects come it. It’s so cool to be walking down the road and find rusty metal or a broken part of a muffler. I always see something in it, and what I can do with it. In fact, the old men in the village I lived in [Goodrich, Michigan] before moving to Traverse City used to leave boxes of old relics at my door.

Did you attend art school or receive any formal training in visual art?

I went to the Center For Creative Studies in Detroit. I have a BFA in printmaking. I went back to Wayne State to get my art ed degree [graduating in 1986 [2]]. My first job in Bloomfield Hills was to teach clay … I also took classes at the Flint Institute of Arts for years just to be able to do something for myself, and to become a better ceramics teacher.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I learned to work and play obsessively. It taught me the value of a good work ethic, and the freedom to learn through play and exploration. Working in a shared studio created opportunities for critiques and camaraderie amongst my peers. It also helped me as a teacher. The importance of keeping a studio organized so that many different students can work in a community without too much strife is important. Developing a work ethic was the biggest thing that I learned, and I’ve been stuck with it ever since.

Describe your studio/work space.

This is my third studio [approximately 250 square feet]. The one I had in Goodrich was above the garage. I had windows that looked out on a beautiful backyard with trees. Everything was in one room — all my found object inventory, my clay, everything. This studio in Traverse City is in the basement. It takes up the majority of the basement — I share a little bit of space with my husband …The main portion of studio has a station for working in clay, a wall to photograph work, a sink that collects all the clay sludge, a shop area with work bench and drill press, a 2D area with my father’s old drafting table, and lots of storage for my littles [3] in cabinets. I have a slab roller that’s portable … I have two easels for when I work on relief pieces — when I’m embellishing them I like to work the easels. And then, I have an entire other area that’s just for my inventory, which I didn’t have before. It’s good, and sometimes frustrating, because I have to go back and forth trying to find the perfect piece or the perfect base; but it’s not far away. It’s very organized.

Is this high level of organization intrinsic to you? Or, the result of years of having many studios?

Years of having many studios, and years of learning from my mistakes. When I’m working in too much chaos, I get lost, and it takes more time. Someone who’s very organized would say, She’s a hoarder; but it’s organized chaos. I know where the majority of things are … When you work with clay — can you hear the raspiness in my voice? — and after 30 years in a classroom with no ventilation, it’s vital that I keep it clean. The sink is big deal to me. We put a ventilation area in here, a fan that will take the dust outside. I keep a Shop Vac in here with a HEPA filter. If I don’t keep it organized in here, it’s bad for my lungs.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

I’m inspired by a sense of place, by nature, by environmental issues, stories, people, figures and an otherness or spirituality that is felt in the natural world. Sometimes I’m just inspired by a piece of junk I find on the side of the road. Some of my work is silly; some people would say “whimsical.” I hate when they say it’s “cute.” People might think “cute” because I love fairy tales. There’s also a dark side to them, and I love the illustrations [of classic fairy tales] … I grew up with a George Roualt print in our house. That print’s illustrative quality influenced me.

Your work is sculptural and figurative. Describe it for someone who may never have seen it.

I’m working with a figure, whether it be an animal or a person. It’s not always in proportion. I like to exaggerate different features to hone in on a feeling. Often the hands are small in proportion to the head, and the feet are large. Faces, many of them have closed eyes in contemplation of what’s going on. If I’m working with driftwood, the driftwood has this beautiful texture to it, a softness from the water. Maybe insects have created lines throughout it; but if I use it for legs or arms in a sculpture, they’re not going to be in proportion. They’re going to be gnarly, like an old person’s arthritic hands. Like my hands. I like that. It adds more to the story for me. It’s not about perfection.

What is it about your work that would prompt someone to describe it as “cute”?

Sometimes people lack the vocabulary to describe it any other way. For instance. I just did a whole series of rabbits. They have expressions on their faces, and their ears have a beautiful suggestion of line to them that takes them beyond “cute.” They’re smaller pieces; but because they’re bunnies or rabbits, people would automatically say the subject matter is “cute.”

Your work is also reflects what you’re thinking about, here and now.

These are the things I’m thinking about here and now: escapism, to be able to go outside. Through this pandemic, and when I was child in difficult times, I would escape to the woods or the fields. It’s my sense of heaven. My sense of peace. That’s been my escape, to try and get outdoors once a day, and hike the power line. The rabbits [have left] footprint in the snow along the power line — no one is going to know that looking at my work — and then there are the coyote footprints … Also, the predator — man — in the environment … We live in an unattached condo where the houses are really close together. In the back of the neighborhood, the builder took out five Mack trucks full of trees. That’s where the bigger home are going to go. It’s cheaper to take the big trees down. It just breaks my heart … I’m making the best of it … and enjoying nature; but that has had a big effect on me. It makes me very sad.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

Sometimes it’s a found object. I’ll find a rusted piece of metal, and it could be a skirt; or a muffler, and it looks like the body of horse. Sometimes my doodles will prompt an idea. Or, I’ll find a stick with a burl, a divot, a pattern created by insects that are so lovely I [see it] as an arm or a leg. Sometimes it’s just getting the clay out, and my thoughts lead me in one direction or another. I’ll pinch it, and it will look like something, and the whole thing that I planned changes.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

I’m going to be in a show in August about heroines.[4] I’ve been doing a lot of research and pre-planning for that. I’m looking up specific women in history who’ve led the way for all women … Right now I have sketchbooks filled with ideas for the heroines project, as well as names and ideas; but I’m working on all of the other pieces for my other galleries.[5]

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Yes. Always. I work in wet clay, creating enough parts to fill a kiln, and my kiln is out in the garage. While those pieces are drying and firing, I’ll be glazing another group of pieces. And when those are done,I begin the assembly process. That can take up the entire studio …

Do you work in a series?

Often, but not always. I find myself leaving a series, then coming back to it at a later time. I’m not sure why. Perhaps I think I’m done with a particular thought; but it keeps coming back in my doodles or play time.

It sounds like doodling opens up portions of your brain to new creative thought.

It does. I think that our sketchbooks are more telling about who we are rather than major pieces of work. There’s a rawness that comes out.

What’s your favorite tool?

My hands. My eyes. Even when I’m not working, I’m seeing on my daily walks along the power line, through the fields and the woods. Working in clay is all about sense of touch, being sensitive to the various stages of the clay — the dryness, the plasticity; it’s vital to the process. Beyond that, I have a tin of clay tools from my father. He was a sculptor and also a clay modeler at General Motors. He made his own tools in art school. I cherish them.

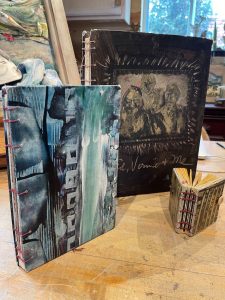

Your sketchbook is another valued tool.

I love sketchbooks. Because my mind can be scattered and I have a bad memory. I know where drawings and lists are in certain sketchbooks. I use them for recipes for glazes, vocabulary terms, for ideas, my imaginings.

How did you think about handwork before you began practicing seriously?

I don’t know that I really thought about it because I’ve always done it since I was a small child. It wasn’t anything I thought differently about. That’s why my hands are my favorite tool. I have to keep them busy. As an educator, I knew the concept of kinesthetics … Knowledge travels from your fingertips to your brain, and it helps memory and fine motor skills and problem solving. That’s not to say that working with computers or working digitally in the arts is a negative thing; but even the educations I worked with who taught digital arts — graphic design, photography, which became all digital — they would have the kids work with their hands as well, using a work journal, writing and drawing …

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

It’s my way of communicating with people. My words are not the best part of me. Working with my hands is my voice.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life? We’ve moved away from it. We’re computerized, and most “handwork” is keyboarding.

True; but I think we’ll come back to it. Just like we got rid of all the shop classes, the woodworking classes — they’re coming back. Our brains all work differently. Many children will be lost if they are only working digitally. Some of them will have an opportunity to have more growth, and be more intelligent if they can work with their hands … [Handwork] helps young people with their fine motor skills and it helps improve their brains and problem solving …

True; but I think we’ll come back to it. Just like we got rid of all the shop classes, the woodworking classes — they’re coming back. Our brains all work differently. Many children will be lost if they are only working digitally. Some of them will have an opportunity to have more growth, and be more intelligent if they can work with their hands … [Handwork] helps young people with their fine motor skills and it helps improve their brains and problem solving …

How do you come up with a title?

It varies. I collect names; the sketchbooks are a great place to store my collection of names. I find them on road signs, poems, in cemeteries. I used to live down the road from a small village cemetery in Goodrich. I wrote down all the interesting names I could find on the tombstones. Often a found object will have a name or number embossed into the metal, and that becomes a [title]. Also, just going on a map and looking at different places. [A “name”] could be a place. When a sculpture is a person or animal, it’s like having a child and naming that child. Sometimes the title is a commentary about what’s going on or a commentary about the piece.

What’s the job of a title?

The job of the title is for me to express what I’m thinking about that sculpture. For some people who see that title along with the piece, they may be affected by it because the title may have something to do with something that’s important to them, or someone who was or is important to them …

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

After art school [1983] I was in a slump. I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to say with my art, what I really wanted to do. Did I want to be a person in their studio working all the time? Did I want to work in a gallery and make my art when I wasn’t making money? Could I make enough money from my art? I couldn’t figure out where my next group of pieces were coming from. I didn’t have a printing press; but I loved to draw and paint. I wasn’t really much into the clay at the time. I received a gift from my father out of the blue [1984]. It was a box filled with menus and labels and newspapers, and postcards, magazine ads, et cetera. He’d kept all of them from the 1950s. They weren’t precious because they were scraps; but they held the key to something new, and I began a series of collages with them. And, drawings with Prismacolor pencils. They were small, very intimate little pieces. I made 30 of them, and I had a one-person show at Paint Creek Center for the Arts. It was the kick starter. That’s when I became serious.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I use it to stay in tune with other artists, to find competitions, and to share what I’m doing in the studio. I love podcasts. I really hadn’t listened to them until the [COVID] pandemic; but I found a few. Hearing other artist’s stories — they may not be working in the same medium I am; but I love interviews with artists as well.

What about Facebook and Instagram?

It’s a way for me to get my work out to the general public, and to receive comments back. Unfortunately, Facebook — there’s a small group of people I hear from. I don’t always get a whole lot of commentary back except for : That’s nice. Instagram — I’ve been able to have more followers and follow more people who I’ve learned from … I used to got to national clay conferences, and would meet famous people in the clay world, who’ve passed away now: Peter Voulkos, for instance. I felt so separated from them until Instagram and the podcasts, so I can actually see what they’re doing on a daily basis, and learn from them. I’m also taking clay workshops through ZOOM. It may not be something I’m learning a whole lot from, [but sometimes there’s] an a-ha! moment [that reveals] a great technique … Instagram, ZOOM, the podcasts: They’ve been educational for me more than they have been something that allows people to find my work …

What do you believe is the visual practitioner’s role in the world?

To share a passion and stay relevant. We’re visual storytellers. History has been told through the unearthed relics, paintings and sculptures. We are such a visual world. Visuals are everywhere, so if artists can be those storytellers, I think that’s a great education for the masses.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

The outdoors. It’s ever-present in my work.

You respond to world events in your work, too.

I’ll respond to that question with the piece Batsh.t Crazy. She pretty much is a reflection of how the world has affected how I’ve felt over the past four years. I’ve seen people who are batshit crazy, and I’ve felt that way. The constant news, the division. I’ve tried to deal with it with humor, more than anger. I did a couple pieces that were more like the [Edvard] Munch painting, The Scream, well. A little more serious, not quite so humorous. It’s gotten to the point I don’t even know how we’re all going to come together anymore.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s a constant. I’ve wanted to live here since I was a child. There’s something about the light, color, skies and the hills. I’ve never fallen in love with them like I have here. I love Michigan. And, I love Northern Michigan — that there are people who had the wherewithal, the money, the means and the dedication to create the different land conservancies, to make the Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes and national lakeshore so everyone can enjoy it. It’s very special.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place? How would we see this?

Absolutely. Many of my pieces have driftwood in them. I’m influenced by the color of the water and the grasses … And the ever present wind we have here. It’s those colors that I’m hoping find their way into my work.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan? Would your work have a different look or appearance?

Perhaps, if I lived in a city, and I was driving on the expressways, I think my work might even be less representational; but I’ve always been surrounded by nature. I’ve always loved it. So I think the themes are more intensified right now. Maybe it’s because I’m retired; I have more time to be outside.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

My father, Michael Tock. My dad worked with found objects … And he was a clay modeler [at the GM Tech Center] … I was surrounded by art. We had so many art books and his art throughout the house, and the artwork he’d bought early on in his career. I remember that I got called in by my kindergarten teacher because I was drawing naked women. My parents had to sit down and talk with me. And I said, I don’t understand. They’re all in the art books you have all over the house. I was very influenced by that. But also, by other artists — because my dad would take me to the DIA.

My father, Michael Tock. My dad worked with found objects … And he was a clay modeler [at the GM Tech Center] … I was surrounded by art. We had so many art books and his art throughout the house, and the artwork he’d bought early on in his career. I remember that I got called in by my kindergarten teacher because I was drawing naked women. My parents had to sit down and talk with me. And I said, I don’t understand. They’re all in the art books you have all over the house. I was very influenced by that. But also, by other artists — because my dad would take me to the DIA.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I would say my dad; but also children books. Those illustrations, those fairy tales. …. My parents were very different. My dad, the artist. My mom, the educator, who loved books. She loved to weave a story. In my quiet way, I fell in love with the two personalities of my parents as seen in those children books and stories — the drawings in them and the tales being told. I could live in my own little fairy land.

How did your father nurture your creativity?

He would be my biggest critic, and it was the best things ever. He wouldn’t say, Oh, that was a pretty picture. He’d truly talk to me about what needed work, and I needed that honest criticism. If he wasn’t sculpting, he was always drafting ideas for homes, or building things.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My husband, Ed York. But I do have a dear friend who is a fiber artist, and we will text images back and forth for honest opinions. I did belong to an artists’ critique group when I first moved here, and we’d gather once a month. That was very helpful.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

It’s my opportunity to have an audience. The process of making is more important; but exhibiting is an honor. It gives me a chance to use my visual voice to share my story, and hopefully strike a chord with the viewer. When someone purchases my work through an exhibition, it means a great deal to me. I appreciate that they’re willing to spend their hard-earned money on art …

Did your teaching cross-pollinate with your studio practice?

Yes. My mantra was: Practice what you preach. I was an artist-educator. I would bring my work into the students … We would critique their work, and they would critique mine as well. I would bring my [advanced placement] students to Goodrich. I would show them my influences and my studio. And take them to Flint Institute of Arts. I had a lot visiting artists come in as well. I would let them see the life of being an artist. I also thought the kids influenced me. We learn so much from people of all walks of life. Teachers don’t know it all, for sure. We learn from our mistakes. One of the reasons I didn’t want to become a teacher in the beginning was that I was terrified that I might say the wrong thing, and a child might not like art anymore. I felt like they didn’t all need to be artists; but they needed to work on not losing their imaginations and understanding the art world …

Were there challenges to doing your own artwork while you were working outside the home?

Yes. I was tired a lot. You get lost in your studio space, and next thing you know it’s 2 am and you have to be up at 4:30 am. It was more of a challenge raising children [6] and teaching full-time and being an artist. As those times became more difficult, and getting a higher degree at the same time — I don’t know how I did it all — that’s when my sketch books came into play. I knew I had to be creative in some way. I couldn’t just set it aside. So, the sketch books are where I put all my creative energy. I still go back to those. If I’m stuck for an idea, I still have those drawings and doodles to bring out inspiration.

Footnotes

1: Michelle taught visual art for 30 years in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in both middle and high schools. She retired in 2016.

2: Michelle also received a Masters in Humanities from Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan in 2000.

3: Michelle’s “littles” are “are my collections of small items such as miniature antique shoes and old hardware (nails, screws, hinges, etc…).

4: Heroines – Real and Imagined, at Higher Art Gallery in Traverse City, Michigan. The dates are August 6 – September 5.

5. Michelle is represented by Higher Art Gallery; Sleeping Bear Gallery in Empire, Michigan; and Twisted Fish Gallery in Elk Rapids, Michigan.

6: Michelle and her husband Ed are the parents of two children, 31 and 27. Between 1993 and 2011, Michelle was dividing her time between parenting, professional work and her studio work.

Learn more about Michelle Tock York here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Kaz McCue

Kaz McCue’s lives as an educator, studio artist, and regular-guy-walking-around-the-place blend seamlessly into one another. Everything is connected. Everything cross pollinates, whether it happens in the studio or the classroom. The 59-year-old Leelanau County resident works in many media, unconfined by a single material or technique. As a art student in the 1980s + 1990s McCue learned about being an artist-citizen, and the concept became a guiding principle. The work of a studio artist, he says, is more than “putting on your smock.” It comes with some responsibilities. This is what he lives. This is what he teaches. This interview took place in February 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

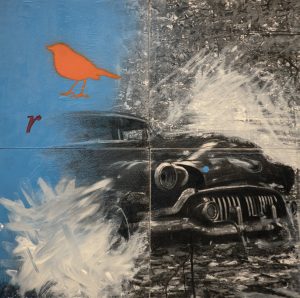

Describe the medium in which you work.

Can’t do it. That’s one of the most basic questions for an artist, and it’s one of the hardest for me to answer. It took me a long time to realize what my place was as an artist, and that was a visual storyteller. As I was coming up through school and working as an artist … I meandered through disciplines, and it took me a long time to realize what I was about as an artist was storytelling. Sometimes my stories needed etching. Sometimes my stories needed photographs. Sometimes they would need sculptures, video. As an artist I don’t box myself into a corner with media. One of the constants through my work is my approach to the photographic image. I have a Bachelor of Fine Arts in photography, and I studied in a very traditional program at Parsons School of Design [1988]. I had very formal training there. And, I love photography. Artistically, I wanted to find more. Because of that traditional training, I was having a hard time experimenting with photography. I found my way out of that corner in grad school. I found a printmaker who was really interested in alternative photographic printmaking techniques … That opened up so many doors, and I’ve stayed on that path. Every time I got stuck, or had an idea I didn’t know how to approach, I’d turn to new media … I’ve probably spent the first half of my career putting tools in my tool box to the point now I’m skilled in a lot of different areas, and I can meander around.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I would say less so than my experiential training. From the standpoint of studying, I put myself in really good spots to learn what I was interested in learning. I was more interested in an individual path than a commercial path. My education was more about the people that I connected and studied with. At Parsons there were an incredible number of professional photographers and artists, and in the 1980s New York was the center of the art world. I was in the middle of it. It was definitely people who mentored me along. [NOTE: Read Kaz’s curriculum vitae here.]

Formal training put you in touch with people who could mentor you?

Yes.

Describe your studio/work space.

I have a parasitic work practice. I’m comfortable working in big, well-equipped workshops, and I’m equally as comfortable working at my kitchen table. I look for opportunities to do the former; but the reality is I spend more time at the latter. Through my career I’ve always found spaces to work … Every time I get a studio space, I fill it with junk. Being parasitic allows me to be a little more fluid. I have the studio at [The Leelanau] school [where he teaches] that I can use on breaks if I have a really big project — I have a 6 foot x 6 foot drawing hanging up in the studio at school right now. My studio is kind of anywhere I’m at. I’ve got a set-up here at my house here in Michigan. I’ve got the art studio at school I can use. I’ve got our house in Florida, which is where my wife [Pamela Ayres] lives and teaches. I’ve a small space down there — oddly enough, I prefer to work on the porch … With my background in material culture studies, I wasn’t working in a clean, white space, like a painter would. I was climbing into dumpsters, and junk shops, and finding inspiration all over the place. It seemed silly to take it out of context.

If we go back to the question about medium — one of the things I do spend a lot of time with is concept. My ideas and what I’m focused on come out in symbols, and concept and context. I feel like my work has a vernacular quality to it. I think it’s because I don’t need anything fancy to make it work. I can do something as simple as a drawing or complicated as a room-sized installation. And depending on the story, I’ll find the space. Right now, with the spaces I have available, I’m pretty comfortable. The shutdown from COVID, and having a lot of alone time was really studio time for me. My studio is where I make it.

Define material culture studies.

It’s a sociological term … The study of material culture is looking at the materials and the objects that a culture uses to gain insight into that culture. For instance, we can look at a chair, and a chair can have a lot of different meanings: from very basic, functional, sitting-down to an annotation of power, or [a symbol of] missing somebody. You can read a lot into a chair … Materials come with inherent meanings that you can then start to play around with. You’ve got pieces of the puzzle that already have some meanings in them. When you recreate new relationships, it expands that. With material culture studies, there’s a pretty straightforward methodology to studying objects, to go from straightforward observation to inference, which is the educated guess you make about the culture. That methodology gave me a platform to build stories … Material culture studies also feed into [his] background in photography. At a certain point, photographs become a cultural object as well.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Well, I’m approaching 60, and a white man in a country that is incredibly confused and divided. Politics, to a degree; but I don’t like those layers to be out on the surface. I’ve been spending a lot of time, in the last 10 years, talking about migration as I’ve become more interested in my own history and background … I’m 100 percent Irish. We came over as skilled labor [in the 1800s] … Death, obviously — I’m getting older. I had a wild path. I never thought I’d make it to this age. I’m probably 10 years shy of when my dad passed away. Maybe not death so much as mortality. I don’t trumpet themes. I inhale them and chew on them a little bit, and put them out there … The things I’m interested in discussing are buried underneath the layers. You have to peel back the layers to get to [the theme, meaning]. That goes to my own approach [to looking at art]. I like artwork that makes me think. I don’t get excited about artwork that spells everything out for you. It doesn’t mean I don’t like that stuff. It doesn’t get me as excited as something that makes my mind work; where I have to figure out what did the artist mean when he did that? Did he mean this? Did he mean that? I play that game with my own work sometimes: Did I mean that? Did I mean this?

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

I see it all as a process. Ideas percolate, and come to the forefront. Other times, they just pop up and move to the back. Right now, I’ve been in Leelanau County for 10 years-plus. I really love it here: I love the seasons, the lake shore, I love Port Oneida [which is] way up there in my focus right now. I’m spending a lot of time crawling around Port Oneida, learning about its history, and thinking about what the place was and what it wants to become … This is years coming. I’ve spent a long time working on Port Oneida as a subject. If we go back to material culture — the barns and the sheds, and there’s even a conversation between the way the farms are laid out — it’s very Eastern European in some cases. I love that history. I love walking those properties, and imagining the people who lived there and made the land work. That has inspired another project, which is four years down the road. Through the process of working, I’ll do one piece that will be, like, Ooooooh, that’s really different. And, I’ll like it; but it doesn’t fit in what I’m doing now. So that piece will go over to the side … Some pieces come really fast. Some pieces come with opportunity. I had an opportunity to do an artist’s residency a few years ago at Villa Barr Art Park in Novi [Michigan]. I’d been thinking about the Irish diaspora. And, I’ve been doing theseboat forms, and all of a sudden I had this chance to explore these boat forms. I ended up doing a sculpture for the park.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project?

In my mind I do a considerable amount. I’ll kind of sit on something, and think about it …. I should go back to talking about my studio practice. In my practice, I tend to binge. So, when I get time, I work intensely to the point where it’s hard to think about anything else. I give myself blocks of time …

You’re very organic about your process. One thing gets started; but there may not be a distinct end to it — you seem to stew, and germinate and muse about things.

In grad school I got to study under Noah Jemison [at Long Island University/C.W. Post Campus]. Noah was a fantastic painter. He lives in Brooklyn, has been part of the New York art scene since the 1960s. The faculty saw the opportunity — they had to have him work with some of the grads. Noah came in and worked with a lot of us. He mentored my wife and me. Noah used to drive me nuts. I was very organized. I had the studio, and I was making a lot of work, and he’d come in to do critiques, and he would never talk about my work. The conversations were, “Hey! Did you see that basketball game last night?” It used to frustrate me so much. One time I got so mad at him, I said, “Look. I’ve spent all this time making this work. The least you could do is talk about this work.” And he said, “Why would I talk about this work? I’m still trying to get to know who you are … I see that you’re making a lot of stuff that looks like art; but I’m trying to figure out if it looks like your art.” And that just messed me up. But he taught me that being an artist was more than putting on your smock and working in your studio. He taught me that being an artist was being an important member of the community. He taught me that being an artist had cultural responsibility. He taught me that being an artist meant being a leader in the arts in the community wherever you can find it. And he taught me that whole idea of being artist citizen*. That just blew my mind. My practice is organic, and it is strongly connected to my life. There’s no way I can separate my art practice from my teaching from my politics from the way I approach community. It’s all wrapped together, which is what Noah was trying to teach me to begin with: Figure out how to make it part of your life.

*Follow-up | Kaz writes: “So, Noah always talked to us about what it meant to be an artist. He would tell us that in order to be an interesting artist, you had to be an interesting person. In the United States, we have a lot of artists who study in college and are well trained; but what Noah was getting at is that it was important for artists to hold a place in the world and then express, reflect, philosophize about that world through their creative work. In other words, it was not healthy for artists to work in isolation or seclusion, and it was important for artists to be a part of whichever community they chose to exist in. Noah stressed the idea of community and how necessary it was for artist to function with the community as contributing members.

“Later, in 2004, Joseph Polisi, who was president of Julliard College, wrote a book titled The Artist as Citizen. In the book he write: ‘Artists of the 21st century, especially in America, must rededicate themselves to a broader professional agenda that reaches beyond what has been expected of them in an earlier time. Specifically, the 21st-century artist will have to be an effective and active advocate for the arts in communities large and small around the nation. … By performing superbly in traditional settings and making the effort to engage community members through their artistry, America’s best young artists can positively change the status of the arts in American society.’ ”

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Yes. I won’t talk to you about how many I’ve got going now. It’s hurting a little bit.

Do you work in a series?

Yes. I binge work. It seems like there’s also a dialogue between the pieces I’m doing at the same time, when I’m going back and forth. I’ll get done, and I’ll think, “That one’s really saying something. That one’s not,” and I’ll not finish it, or move it to the side. When you’re writing a story, you do edits. I’m doing the same thing … I like to feel like I’m living the postmodern life, and that’s just part of it, having all these little tributaries that you can meander down. And, if one doesn’t work, you can come back and go in a different direction …

What’s your favorite tool?

Definitely the arc welder. I love welding. I started with ceramics — very tactile. And then I went to photography. And then I went to printmaking, and sculpture. But when I got to sculpture, that practice matched my personality. I love teaching it, too. I love welding because there’s a sense of power to it, and also a sense of immediacy to it. You can have an idea, and see it right there.

It’s a high-powered gluing machine.

Yes. You have a piece of metal, you stick it on there and look at it. If you don’t like it, you can break it off. When I was working on that piece for [Villa Barr], I worked for two days straight, and I was going nowhere … I called my wife, who’s probably one of the people I get the best feedback from, [and told her], “This thing’s a disaster. I don’t like it. The form isn’t right.” And she said, “What would you tell your students to do?” And I said, “Cut it apart, and start over.” So, I cut it apart, and started over. You have that power with welding. It’s like drawing in space. I love that. You get to see something three-dimensionally, that interacts with space. And, I love that I can [make] something as big as me [5 foot, 6 inches tall], or bigger than me, and it stands on its own.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I’ve got them laying all over the place.

How did you think about hand work before you began practicing seriously?

I was raised in a middle class family. My sister and I had art lessons. We both went to Catholic school. Catholic schools didn’t have a lot of arts programming. It was instilled in me that I have to study hard, and be good academically, and art was fun; but it was not what was going to build my life. My mom was a corporate executive in the ‘60s [a vice president with Swiss chemical giant Ciba-Geigy], so she pushed hard for us to do well academically. So I had a different trajectory. I was going to go to school and become a veterinarian. And then my dad passed away my senior year, and that put everything in a twist and my life unraveled from there. So, for me, working with your hands — I was torn over it … My dad was a self-employed roofer, always worked with his hands, and that’s what I thought about hand work. And my mom, who was a white collar worker, who was very successful, and very powerful …

It sounds like, in your family, brain work was the highest-level work, and hand work was something that had practical usage; but it wasn’t what one should aspire to.

Yes. Because of my dad’s work, I had access to hammers, and saws, and nails. We built tree forts. We built jumps over my mother’s azalea bushes. We built go-carts. We did all that stuff; but that was for fun …

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

I’ve had the opportunity to work with kids with disabilities. They’re following careers [of disabled people] like Chuck Close, who has that terrible stroke, and came back to have a really remarkable last portion of his career. I’ve often thought about what happens if I couldn’t make anything by hand, and the thing is it’s an important part of my identity, like it was for my dad. I’ve spent a long time trying to get closer to my dad by being more like him. He was very soft-spoken. Never raised his voice. Never got mad at me, no matter how stupid I was. He was kind and sincere and a wonderful person. I hope I’ve been able to become more like him … [Making-by-hand is important] because it’s who I am. If I lost that ability, I’d be a different person. I’ve thought about it because of working with people who’ve had to deal with it, and I know I’d be able to figure it out, but I’d be a different person.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life? Or, not?

[Kaz holds up cell phone and pantomimes tapping the keyboard.] This is not working with our hands. I try to tell my students that all the time. That’s working with a funny little rectangle and exercizing your fingers. There’s a reality to hand work that you just can’t replace … We have two lobes to our brain, and if we’re going to be human beings, and good human beings, we want to exercise both parts of our brain. If we live more on the left side of our brain — if we’re an accountant, or doing high-functioning math on a daily basis — we need something to put us on the right side of the brain … Brains need to be in balance, and that cross-over is really important … When I talk with my students about this, I talk about observation. When you’re sitting there with a piece of paper and a pencil, and you’re looking at something and drawing it, you’re doing direct observation. You’re observing things you can’t get in a photograph. And you can’t replace first-hand observation. You can look at an orange all you want on your phone; but until you actually peel the rind, get a little zest sprayed in your face, it’s a different experience.When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

I’ve had two points in my career. The first was when I was at Parson, and I was working for a still life photographer in New York. Another wonderful individual who towed me along. A great guy. He took me in. I was his first, full-time assistant in his studio. We were doing ads for American Express Platinum, Scalamandre fabrics, and Shaw carpets. He did a lot of work for Interiors magazine. One day he brought his portfolio from his thesis show, and I was looking at it, and said, “You’re really an amazing fine art photographer. What made you decide to go into commercial photography?” And, it was very simple. He said what he wanted from his life was to make a nice living, get married, have a house, and have a family. He had a similar experience like mine: He worked for a commercial photographer in Chicago, gained that experience, and decided that was the direction he wanted to go in. That was my first real lesson: Make a decision. If you want to be a commercial photographer, and make money, and have things, you have to understand you’re providing a service. You’re not making art. You’re providing a service. If you’re good with that, you’ll be happy. But if you go away thinking you’re an artist, and the client thinks you’re providing a service, then you’re going to be unhappy. On the other hand, if you don’t want to work for someone else and do what they want, when they want, on their timeline, then fine art photography is great way to go. I decided, based on that conversation, I didn’t want to have anybody tell me what to do … Having the wherewithal to make that decision also meant I had to give up the semblance of making money …

And then I met Noah, and Noah taught me about community. While he’s teaching me to learn who I am so I can understand my art better, he helped me to understand who was my “audience” — and it was my colleagues and professors at in the grad program at C.W. Post — he helped me to realize I didn’t really like that audience. The people I wanted to speak to were my friends, my family, and the people who would always come to my art show, and say, “This is so amazing. I don’t understand what any of it is, but it’s awesome.” Those are the people I want to understand, to connect with, to tell stories to. That’s were material culture [studies] started to creep back in. I realized I could use objects, and that would give people a way in. Things started to fall into place.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Not much. My work, to a certain degree, goes against technology. One of the themes I have worked with throughout my whole career is the deconstruction or decomposition of photographic images. When I was studying in New York, there were a couple of guys who’d graduated from the School of Visual Arts, Doug and Mike Starn. They were superstars in New York in the ‘80s, and they really took the idea of a photographic image to another level. They cut it apart, taped it, and glued it, and nailed it back to boards. They didn’t care about archival-ness. So I got to see some cool stuff; but I’ve loved that whole idea of what is a photographic image? From an historic and artistic standpoint. There’s a lot of hidden stuff to photography. A lens distorts reality. It manipulates it. And when we’re in the darkroom or working on a computer, we manipulate it some more. When we look at photographs, we tend to accept them as truthful information because of our visual culture. The thought of social media and imagery weighs on me all the time. If you get a group of 100 people together and ask how many have painted, you might get, maybe, a quarter of them to raise their hands — if the odds are high. But if you asked them if they’ve taken a picture, 100 percent of them will raise their hands. Everyone has taken a picture. What’s changing is the codification of visual imagery in our culture — because of social media. And, technology. When George Eastman came out with the Brownie camera, you paid $25 and you got this camera with 100 pictures in it, and you shot pictures of your world. You’d send it in, and they’d send it back with a new roll of film in the Brownie, and you’d start all over again.That act of bringing photography to the masses had a huge impact on our culture. Look! Here’s a picture of the new cow, let’s send it to Johnny who’s in college. Now everybody has a phone in their pocket. Everybody. And, we treat images very differently. Images are almost becoming more codified than language at this point … I’m really more interested on the effect social media is having on culture, than the social media itself.

What’s social media’s influence on the work you make?

I don’t know if I’d say it has an influence … I like looking through old books. I have a lot of old books. That’s what the sketchbooks are for: it’s a place to collect ideas and images, thoughts. That becomes a place for sourcing. This came about as working as [an educator]: We don’t talk about sketchbooks. We talk about them as source books. That terminology — at least, working with students — has given students the permission to put anything [in the sketchbook]. They can say, “I don’t sketch, so a sketch book isn’t important to me.” But, you need a place for your ideas.

What do you think is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

Years ago my friend wrote a book called Creative Options for Contemporary Art. I loved this book, and I learned a lot from it … It talks about universal concepts for creative individuals: Understanding your audience. Sourcing inspiration — where do your ideas come from? What is your artistic attitude? As I alluded to, my artistic attitude is that of a 50-something-year-old, pissed-off, American white guy. What is my approach to my work? I take the approach of an interpreter. I like to interpret, recreate relationships. One of the other things: What is your mission? It really depends upon what your mission is as an artist? Your mission may be to paint pretty pictures, and that’s a great mission. And then you figure out how you measure success against that. My mission is to be a storyteller. So I measure my success against that by how many stories I can tell that connect to people … When you making stuff, if your mission is to be a storyteller, you measure your success on how well people can engage with that story. In some cases they may just engage with it for entertainment. In some cases they may engage with it for intellectual stimulation. In some cases they may engage with it because of the material connection. There’s a lot of ways to approach that. That becomes a very individual question.

Years ago my friend wrote a book called Creative Options for Contemporary Art. I loved this book, and I learned a lot from it … It talks about universal concepts for creative individuals: Understanding your audience. Sourcing inspiration — where do your ideas come from? What is your artistic attitude? As I alluded to, my artistic attitude is that of a 50-something-year-old, pissed-off, American white guy. What is my approach to my work? I take the approach of an interpreter. I like to interpret, recreate relationships. One of the other things: What is your mission? It really depends upon what your mission is as an artist? Your mission may be to paint pretty pictures, and that’s a great mission. And then you figure out how you measure success against that. My mission is to be a storyteller. So I measure my success against that by how many stories I can tell that connect to people … When you making stuff, if your mission is to be a storyteller, you measure your success on how well people can engage with that story. In some cases they may just engage with it for entertainment. In some cases they may engage with it for intellectual stimulation. In some cases they may engage with it because of the material connection. There’s a lot of ways to approach that. That becomes a very individual question.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

I’ve been here for 10-plus years. I love it here. I think it’s incredibly beautiful year-round. That has creeped into who I am as a person, which inevitably creeps into who I am as an artist. I feel very connected to this place. I find that more and more my thoughts and ideas are wrapped into this sense of time and place. Any artist you talk to is making art to reflect the world around him. This is an important part of my world, so I spend a lot of time talking about it.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

Oh yeah. I know I would.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

No. However, my folks emphasized the arts. With my mom’s job, we were always going to art exhibitions and performances. When I was younger, I got to see Dizzy Gillespie play, Cab Calloway play, a couple of time. Storm King Arts Center is near where my family was from. Alexander Calder’s studio not too far away from where we lived in Connecticut. I was always exposed to the arts, but never really went into a professional artist’s studio until I met Michael Whelan. I was in my early 20s at that point. Now, my cousin got married in the old St. Patrick’s Church in New York City in the late 1960s. They had their reception in a friend’s loft, and we could see through the floor boards to the studio below.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

It has to be Noah. That man did so much to open my eyes, and really help me go from being lost in my work to someone who found themselves within their work. He was such an important influence. He still is. I can still hear his lessons. I still talk to him … He [also] had an influence on how I teach, and how I work with other artists, how I act as a person.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

That’s my wife’s job. We’re brutally honest with each other. We met in grad school in 1990, and been together since. We both have similar philosophical approaches to art. We were both mentored by Noah … We’ve worked together a lot, and we’ve worked apart a lot. We have level of language and communication when it comes to art that we both trust each other implicitly with feedback. We don’t always listen to each other,but the feedback is always strong and valuable.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

I could tell as many stories as I want to at home, and no one is going to hear them. You have to put the work out there. I have a mixed relationship with exhibiting. Painters’ studios are based on a 19th century model of a French painter: white walls, bright light, and the gallery is basically a white box meant to imitate a painter’s studio. My work’s not created in that way. I almost feel as though I’m taking it out of context that way. I love public art. I love when I can put art out in the public. The context is different. I’ve started doing more publications. And, I’ve actually got new twist on a photographic idea I’m working on. Even though “audience” is a theoretical idea, you have to get your work in front of viewers.

Why?

How do you know if you’re doing what your mission intends for you to do or not. With COVID, I’ve been focusing on the work, and have made an awful lot of work. In the exhibition world, everything has been pushed back. I didn’t have anything lined up before COVID started. I’m trying to stay out of the fray for a little bit, but I am starting to think about showing my work. That’s probably going to be my next project — look for a solo exhibition for my more recent work.

Let’s talk about your day job.

I’m instructor of visual arts at The Leelanau School. This is my 11th year teaching there. I teach film, photography, studio art, graphic design, and an experiential high school curriculum.

What is “experiential” curriculum?

At The Leelanau School we work with kids who are struggling with learning. We teach them how to learn, so our program is experiential. That opens us up to addressing different style so learning. If we can teach kids how to learn, they can learn anything. When you look at public standards curriculum, these standards are superficial, and designed to skip along the surface. They don’t address content. They don’t address practice. What we’re doing with our kids is trying to build their learning skills and process by going to a subject, and going deep, and really exploring it. It’s a very Foucaultian approach. You go into one pin point in history and then you explode that, and look at everything that was happening. So, if you want to look at the Ballet Russes for instance, you have to look at all the Modern Art that was happening in Europe. You have to look at what was happening in art history in Russia. You have to look at politics, and world conflict. One simple subject gives you an opportunity to go really deep and explore. That’s where learning starts to happen. Through that experience, we’re trying to create a scenario where the students can learn their learning skills so they can find their way through difficult subjects, for them; and then also building for the future. We are a college prep school, so our intent is to get kids ready for college. A lot of things I talked about with my practice really relates to this. My practice is very process-driven, and my teaching is the same way. My day job and my other job complement each other … [Kaz picks up his cell phone.] And again, these stupid things fight our process. We can’t tell the kids, “No, you can’t use your phone”; but they have to learn to use it properly. That experience becomes part of their learning. That’s a cool place to be. One of the reasons I feel so comfortable here is I’ve found a place where there is a strong sense of community, and we do a lot of our teaching through that sense of community. It’s not just about the academic classes. We are getting to build the whole kid, and that’s really cool. I’m able to be myself, which is incredibly valuable. Again, I chose my path not to make money, and to become wealthy. I’ve had a good life, and a lot of rich experiences, so I tend to measure my wealth in experience.

What challenges does teaching present to practicing your own work?

It’s always time. I’ve had good opportunities as an artist-in-residence. But that’s always the discussion — having the time and the resources to make art. That’s always the hard part for artist. And when you’re working a job, it’s eating into your time and your resources. If I were to go to a place where I had the time and resources, I probably wouldn’t be able to afford all the stuff I need to live my life the way I’m living it right now: the car, the tools, the cameras, the frames, all the art materials.

How is your studio practice supported by your employer?

At The Leelanau School, creativity is incredibly important to the entire community. Our community embraces the arts. They embrace me as an artist. They put up with me, with my crazy ideas both for myself and my students. They know if I get some harebrained idea, there’s enough trust there to know it’s going to turn into something cool for our students … I feel very supported. I can use the studios in the off times. There’s a great darkroom, and room to spread out … I really feel like I’m in a place where I’m not in a rut. If I were in a rut, teaching wise, it would be very hard … The hardest part of my life right now is my wife is in Florida, and I’m here. This is our eighth year of doing that. In our 25 years of marriage, we’ve been living in different cities more than we’ve lived together. Our goal right now as we’re getting on in years and starting to look at retirement is that we’ve both committed to being here. But when you have two art teachers with similar skill sets, looking for employment in the same place — like Leelanau or Grand Traverse counties where there’s not a lot of positions to begin with — it’s a hard scenario to work out. It would be wonderful to find a patron who could support us, and put us together. That’s why I play the lottery.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I’m a voracious learner. I love doing research and learning new things about old subjects. Really, my work reflects my own curiosity.

What drives your impulse to create?

Possibly, it might have something to do with my upbringing. I guess I always felt like I didn’t have a voice when I was younger. Everyone always told me what to do so I felt as though I was always pushed to the background. I found my voice through my creativity and feel like I can confidently tell stories about who I am and what I’m about.

Read more about Kaz McCue here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Susan Tusa

Photographer Susan Tusa learned her craft in the days before digital, and plied it in the field of print journalism. She was a staff photographer with The Detroit News; and The Detroit Free Press, from which she retired in 2012 after 22 years. Susan is the recipient of numerous awards, and has exhibited her work in Michigan and France. During her decades as a news photographer, Susan created lyrical images that hinted at the kind of images she might create when not tasked with the work of reporting. She resides in Empire, Michigan.This interview took place in April 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

What draws you to the medium in which you work

That’s a difficult question at this point in my life. I’ve been photographing pretty much daily for 40 years. It’s just what I do.

Did you attend art school or receive any formal training in visual art?

My formal training was very limited. On a bit of a lark, I took a photojournalism course at Michigan State University and fell madly in love with the whole thing: the going out and shooting, and coming back and processing the film; then it magically appearing like a memory. I was at MSU thinking I was going try to become an environmental reporter. It hadn’t been a well-formed idea. I was just taking courses. And then I took a photojournalism course [in 1976-77], and completely changed directions. It hadn’t occurred to me that a person could make a living doing something they loved. I had purchased my first 35 mm camera a year earlier with money from unemployment checks [1]. I took a couple of courses per semester so I could work at the college newspaper [State News], and then doggedly pursued a career in photography. I started at small town weekly newspapers photographing things like little league tournaments and Farmer of the Week.

When so many people are working with digital cameras and technology, that darkroom magic is unknown or foreign to them. Is this a loss, the lack of direct experience in the darkroom?

Yes, I do think it’s a loss.

I think the more we know about, and the more we experience, in regard to any art we are practicing, widens our view. Having firsthand knowledge of different aspects of craft deepens the experience of not only practicing art, (in this case photography), but viewing it, and understanding it. I’ve met young photographers who have never even focused manually, and always use auto exposure, and I wonder how they can possibly get the results they want. The camera certainly doesn’t know, at least not yet. I think it’s really important to know the equipment you’re using and what it’s capable of. I also think that instant results cultivate unreal expectations, and an impatience that can be detrimental to producing good work.

I think there’s less time for contemplation, and that sense of what a photo actually is: a moment in time, a recent memory. The darkroom experience really illustrated that. You watched this moment from a while ago slowly appear. It’s a ghost, a mirage, and then it’s solid.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

Like I said, my formal training was limited. The photojournalism courses introduced me to the basics of black and white 35 mm photography – exposure, the function and relationship between shutter speed and F-stops, controlling depth of field, that sort of thing. I learned how to develop film, make black and white prints, and the importance of getting to know your subject. One of the first assignments I recall, was to come up with 10 portraits of people on the street – perfect strangers – and hand in not only quality prints of each person, but brief biographies. I discovered that I loved talking with strangers and finding out about the different lives they lived. And I was surprisingly comfortable doing it. (I’m not sure why, maybe from years of watching my mom talk with cashiers, plumbers, the guy on the phone, the mail carrier, pretty much anyone she came in contact with.)

The rest of my education was trial and error. Lots of error. I remember while working at The [MSU] State News, my boss, a prickly sort, sent me to shoot an advertisement at a women’s clothing store. He loaded me up with a closet full of equipment I had never touched — lights and batteries, umbrellas and light stands — and sent me off to shoot the ad. He was a bit terrifying. So, rather than speak up and admit that I hadn’t a clue how to use any of the equipment, I muddled through with predictably terrible results, and got fired. It took a while, but after a lot of experimentation and wasted film, I learned to manage lights quite well. After I was quite comfortable with them, I found myself avoiding them whenever possible anyway, even when shooting food or fashion. I always prefer shooting on location or using window light and reflectors. Too much equipment always feels like a barrier to me, and I never thought that the artificial light I created was as pleasing or effective as the light of the world.

Describe your studio/workspace.

I practice photography everywhere: inside my home, outside, wherever I am or wherever I am assigned to go. Most often, these days, it’s wandering the trails and shore of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

My editing/printing space is in the bedroom/office/laundry room in the little house I just moved into. It’s tight, but it works – a perk of not needing a darkroom anymore. Years ago, pre-employment, I made prints in my bathtub. My enlarger was on small back porch that I blackened with dark plastic bags, towels and lots of duct tape. Now I do all my “developing” on the computer. I’m quite comfortable doing what I used to do in the darkroom, in Photoshop, and since I left the Detroit Free Press. I’m learning to feel free to make more adjustments than I was ever comfortable with. When working as a photojournalist, it’s not acceptable or ethical to alter photos in any way. Basic toning — that’s it. If I photographed someone and didn’t notice the bushy tree in back of them looking like an eccentric’s hat because of the angle I chose, well, too bad. We don’t alter reality. I get so angry at people crying “fake news” when I’m well aware of how the vast majority of journalists and photographers work so hard to produce an accurate representation of whatever the subject, story, or situation is. Even now, when I’m doing a close up of something in the woods, I feel a twinge of guilt if I remove a twig from the scene; but I’m getting over that little by little as I work on artwork. I’m becoming a bit more playful, because I can be.

You have been in the process of transitioning from your professional work as photojournalist with the Detroit Free Press to the work of a studio artist.

I left the Detroit Free Press at the end of 2012. I don’t consider myself a studio artist. I approach my work in much the same way I always have.

How are the two forms of photography alike or different?

I don’t think there is a big difference between the work I did at the Detroit Free Press, and the work I’m doing now except the content and pace. I rarely have deadlines, don’t have daily assignments, and live in a different place. I’m still photographing most days, and when I’m not, I’m editing, printing and trying to figure out ways to make this daily practice of mine useful. I’m trying to sell my artwork, which is relatively new to me. I’m fumbling my way around the art world, figuring out pricing, limited editions, that sort of thing.

Which of your photojournalist’s tools/equipment have transferred to your studio work?

My tools are pretty much the same, except that I don’t have as many cameras and lenses. The paper used to provide whatever we wanted in terms of equipment, and now I have to buy my own, so I can’t afford the really long lenses I’d like; or to replace my older cameras with the newest, better, faster versions.

What did you bring [visually, philosophically, aesthetically] from your former profession into your studio work?

My visual, philosophical, and aesthetic approaches to my work have developed throughout my career. And they continue to develop and change as I do. As a photojournalist I’ve had to photograph everything – portraits, prison riots, fires and fashion, the rich and famous, the poor and impoverished, violence, kindness, mayhem, quietude. The challenge was always to get to the truth or essence of whatever it was I was shooting, make it visually interesting/artful in terms of composition and content, and fulfill the needs of the paper – the space it was destined for. The difference now, is that I’m most often photographing with no assignments, deadlines, or the demands of a particular publication.

But I always have a camera, and inevitably something will catch my eye: a shift in the light, a sound, some movement on the ground or something incredible at my feet that I’ve never seen before. Whatever it is summons me to stop and look more closely. I’ll begin shooting, and then I’m pretty much lost to whatever drew me in. I’ve always loved being in nature, where life and death and the whole mysterious mess becomes less scary. The “I” is replaced by a kind of mindfulness.

Please elaborate.

When I begin photographing something, and “working” it, nothing else exists. I’m not thinking, just seeing and making adjustments in focus, depth of field, shutter speed, changing my position — standing, kneeling, laying down, watching the scene or whatever it is change in the viewfinder, shooting frame after frame. I’m not thinking about the past, or worrying about the pandemic or politics, mass extinctions, what I’m going to make for dinner, or the million other things that are always scrolling through our minds. All I’m doing is seeing.

In the Washington Post article about the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, which your photographs illustrated, Rebecca Powers said you “often recite poetry while hiking.”

I don’t have a lot of poems committed to memory, but sometimes I’ll think of a part of a poem and look it up. I like trying to memorize poetry while hiking. I find it easier when I’m out walking to memorize things. Sometimes walking, a poem will occur to me, and I’ll incorporate it in the pace of my steps. A few poems I know by heart are like prayers, particularly a couple by Mary Oliver. She’s so in tune with nature. It’s a nice way of centering.

Thinking about poems doesn’t take away your focus from your walk, and the seeing part of your walk.

It’s almost like the walk and the seeing conjures up the poem. I never memorized a lot of poems throughout my life; but now, it’s probably a good idea. My legs are moving. I want to get the brain to do a little work, too.

I used the verb “illustrated” to refer to your images in the Washington Post article; but I don’t think that’s accurate. Your images stand on their own as much as Powers’s words stand on their own.

The words and photos aren’t supposed to mirror each other. Ideally they work together to communicate and make a connection with readers/viewers.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Life, death, the all of it, I suppose.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

I’m not a pre-planner. I might return to something I’ve seen when the light is better, which for me usually means softer or darker. Even when I do still life photography, there is no real plan. I begin with something I might’ve picked up — a rock or dead bug — and go from there.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

I always have several things going at once; but I’m very unorganized and photograph an unmanageable volume of work. I have hundreds of thousands of files and negatives in boxes and folders, on hard drives and my computer desktops that need editing. During the summer months, when the light is harsh, and the heat and chaos are a bit much for me, I spend time inside editing and trying to create some order out of the chaos. I have an embarrassing number of folders on my desktop computer, and lately I’ve been doing nothing with them except adding more images. Each of these folders represents a potential series or project; but at this point they are becoming less defined and more unwieldy.

What’s your favorite tool?

Whatever I happen to be using or have with me on my walk. My Canon 5D Mark II with various lenses is what I like to shoot with most; but it’s also heavy and weighs me down [2] when I’m walking a few miles at a time. Sometimes I’ll carry a point and shoot, and always my iPhone. If I leave the Canon behind, I can be sure I’ll come across something particularly beguiling and I’ll regret it, so I try to have my camera and at least one lens with me. I purchased one of the new iPhones, simply for the camera. I justified the purchase while dealing with a shoulder issue not too long ago. The capabilities of that camera are astounding; but I also have to be careful not to submit to the convenience, because the days that I do, are inevitably the days when I’ll kick myself for not carrying the heavy stuff.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I always carry a notebook and write down random thoughts that might occur to me, or that I might want to expand on. A couple of years ago I completed a master’s degree in creative writing [3], and am in the process of trying to combine the two arts. It’s really a difficult and interesting process. I’m still a novice in terms of writing. My writing is about as organized as my images. Folders, both physical and virtual, notebooks, scraps of papers, piles of them all over the place.

How do you come up with a title?

I’m terrible at titles. Generally, I try to keep them simple: a geographical location, a botanical I.D., or “untitled” if I can’t think of anything. My daughter cured me of trying to come up with meaningful names when I was getting my first exhibit together. We laughed pretty heartily at how lame the names I was coming up with were. She is my go-to editor. Never afraid to tell me the truth or hold back an opinion, and I trust her eye and judgement.

What’s the job of a title?

I’ve learned, that for me, a title is simply a point of reference. Like a number. If the image is particularly abstract, perhaps a word or two as a way to orient the viewer. I don’t like titles that qualify the subject in anyway or tries to induce a reaction in the viewer. I never use a title to spell out a particular emotion or whatever it is that I’m trying to communicate. I think it’s somewhat disrespectful to the viewer. If what I was trying to communicate isn’t within the photo, the image failed.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

When I took my first photography course.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I’m active on Instagram and follow visual artists from all over the world. Looking at images every day is inspiring. Paintings, photos, sculpture, all of it. Every encounter we have with art affects us, I think, and influences the slight shifts in direction our own art takes. Whether that encounter or immersion is via social media, an art gallery, in books or films, it all becomes a part of us.

What’s its influence on how you let the world know about the work you make?

I think it’s a way of getting work out there. As your community grows, so does exposure. I’ve gotten some freelance work that way, sold some art, and was asked to participate in an exhibit through Instagram.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

To make art.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

I believe that everything is connected to everything else, our memories and histories, all of it affects who we are and our world view. I guess every part of the world I’ve had the privilege to be exposed to – physically, virtually, intellectually. All of it has somehow found its way into my work. I could look at one of my recent photos and say, for example, this photo is because as a child I went to a Catholic girl’s school or because I recently read a novel by Chris Abani, or because I took a walk and saw that dead mouse, all of it’s in there somewhere isn’t it?

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

Nature is pretty much center stage here, and since I moved to Empire full time a couple of years ago, it has taken center stage in my work too.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place?

I think my work is definitely a reflection of wherever I am, both physically and mentally.

If not directly reflected or depicted in your work, are there other [unseen] ways Northern Michigan informs your work?

I’ve spent the majority of my life in Michigan, so my work most likely carries the sense of Michigan.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan? Would your work have a different look or appearance?

There would be different content, of course, but I’m sure there would be similarities in the mood or texture of the photos. I lean toward the quiet, and solitary, sometimes dark, whether in color or black and white. My color photos are most often monochromatic. That said, if I lived in Cuba, say, I’m pretty sure I’d be photographing the rich color palette there.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

Just an uncle who I rarely saw.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

When I was younger, I read a biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, and was awed by her vision and the way she lived her life. That might have been one of the sparks that first pointed me in the direction of visual art. I didn’t grow up in an artistic household. I took piano lessons in the first grade; but a cranky teacher convinced my parents that I was not musician material (and this was after having just mastered “Yankee Doodle”). I have no memory of trips to art museums, art lessons, things like that.

It’s difficult for me to name one person. I’ve had the privilege of working alongside some of the most talented photographers and editors out there – Eli Reed, Stephanie Sinclair, Taro Yamasaki [4], Joel Meyerowitz, Joyce Tenneson, Romain Blanquart, Kathy Kieliszewski, David Gilkey — at the papers I’ve worked at, on various assignments, and during different workshops. Some are well known, some are not. But their collective knowledge and different ways of seeing widened my vision and continues to do so.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My daughter. She’s not afraid to say exactly what she thinks, she’s smart and funny and has an incredible eye.

You’ve moved from having a reliable, regular platform for your “showing” work — i.e. The Detroit Free Press — to a place where you are asking people IF they’d like to show your work.

Entering exhibitions — I didn’t even realize that that was a thing. The first exhibition I was a part of, I was contacted by a man who was curating exhibitions at the Detroit Artists Market. I just thought gallerists found you. I’m starting to learn the process.

Exhibitions are prohibitively expensive in terms of getting the framing done. I’m particular and don’t make frames myself. And then you have to figure out prices. I have a friend who’s been doing this for a while, so she’s been advising me on the business end of things. It’s probably a good thing I had a regular job because I’m really bad at it. I’m trying to get better because I’d like to get my work out there and sell it.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?