Creativity Q+A with Michelle Tock York

Michelle Tock York, 60, is a sculptor working in clay, and with a wide range of intriguing found objects — from organic finds [e.g. driftwood gleaned from the beach] to trinkets and forgotten objects scavenged from antique stores and other treasure troves. Her goal? To turn all these disparate materials into “cohesive” works that tell the stories this Traverse City artists wants to tell. This interview took place in March 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity.

You work with clay in a sculptural way.

I do have a potter’s wheel … but I’m definitely not a potter. I love hand building. I had to know [wheel] pottery well enough to teach it at the high school level [1]. I taught the [college level placement] classes.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

I love the push and pull of the clay. I was a print maker in college. I loved manipulating the [printing] plates; but it’s the actual touching the clay that’s exciting to me. I love creating something out of a blob of dirt. As a child, my parents loved antiques. They would drag me to every antique store, and I began to love the found objects, the cool old toys that I’d find in there, wood that had a patina and a history … That where the found objects come it. It’s so cool to be walking down the road and find rusty metal or a broken part of a muffler. I always see something in it, and what I can do with it. In fact, the old men in the village I lived in [Goodrich, Michigan] before moving to Traverse City used to leave boxes of old relics at my door.

Did you attend art school or receive any formal training in visual art?

I went to the Center For Creative Studies in Detroit. I have a BFA in printmaking. I went back to Wayne State to get my art ed degree [graduating in 1986 [2]]. My first job in Bloomfield Hills was to teach clay … I also took classes at the Flint Institute of Arts for years just to be able to do something for myself, and to become a better ceramics teacher.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I learned to work and play obsessively. It taught me the value of a good work ethic, and the freedom to learn through play and exploration. Working in a shared studio created opportunities for critiques and camaraderie amongst my peers. It also helped me as a teacher. The importance of keeping a studio organized so that many different students can work in a community without too much strife is important. Developing a work ethic was the biggest thing that I learned, and I’ve been stuck with it ever since.

Describe your studio/work space.

This is my third studio [approximately 250 square feet]. The one I had in Goodrich was above the garage. I had windows that looked out on a beautiful backyard with trees. Everything was in one room — all my found object inventory, my clay, everything. This studio in Traverse City is in the basement. It takes up the majority of the basement — I share a little bit of space with my husband …The main portion of studio has a station for working in clay, a wall to photograph work, a sink that collects all the clay sludge, a shop area with work bench and drill press, a 2D area with my father’s old drafting table, and lots of storage for my littles [3] in cabinets. I have a slab roller that’s portable … I have two easels for when I work on relief pieces — when I’m embellishing them I like to work the easels. And then, I have an entire other area that’s just for my inventory, which I didn’t have before. It’s good, and sometimes frustrating, because I have to go back and forth trying to find the perfect piece or the perfect base; but it’s not far away. It’s very organized.

Is this high level of organization intrinsic to you? Or, the result of years of having many studios?

Years of having many studios, and years of learning from my mistakes. When I’m working in too much chaos, I get lost, and it takes more time. Someone who’s very organized would say, She’s a hoarder; but it’s organized chaos. I know where the majority of things are … When you work with clay — can you hear the raspiness in my voice? — and after 30 years in a classroom with no ventilation, it’s vital that I keep it clean. The sink is big deal to me. We put a ventilation area in here, a fan that will take the dust outside. I keep a Shop Vac in here with a HEPA filter. If I don’t keep it organized in here, it’s bad for my lungs.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

I’m inspired by a sense of place, by nature, by environmental issues, stories, people, figures and an otherness or spirituality that is felt in the natural world. Sometimes I’m just inspired by a piece of junk I find on the side of the road. Some of my work is silly; some people would say “whimsical.” I hate when they say it’s “cute.” People might think “cute” because I love fairy tales. There’s also a dark side to them, and I love the illustrations [of classic fairy tales] … I grew up with a George Roualt print in our house. That print’s illustrative quality influenced me.

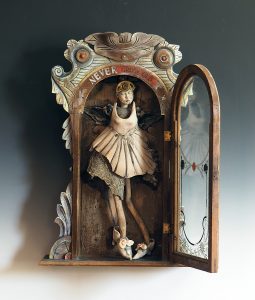

Your work is sculptural and figurative. Describe it for someone who may never have seen it.

I’m working with a figure, whether it be an animal or a person. It’s not always in proportion. I like to exaggerate different features to hone in on a feeling. Often the hands are small in proportion to the head, and the feet are large. Faces, many of them have closed eyes in contemplation of what’s going on. If I’m working with driftwood, the driftwood has this beautiful texture to it, a softness from the water. Maybe insects have created lines throughout it; but if I use it for legs or arms in a sculpture, they’re not going to be in proportion. They’re going to be gnarly, like an old person’s arthritic hands. Like my hands. I like that. It adds more to the story for me. It’s not about perfection.

What is it about your work that would prompt someone to describe it as “cute”?

Sometimes people lack the vocabulary to describe it any other way. For instance. I just did a whole series of rabbits. They have expressions on their faces, and their ears have a beautiful suggestion of line to them that takes them beyond “cute.” They’re smaller pieces; but because they’re bunnies or rabbits, people would automatically say the subject matter is “cute.”

Your work is also reflects what you’re thinking about, here and now.

These are the things I’m thinking about here and now: escapism, to be able to go outside. Through this pandemic, and when I was child in difficult times, I would escape to the woods or the fields. It’s my sense of heaven. My sense of peace. That’s been my escape, to try and get outdoors once a day, and hike the power line. The rabbits [have left] footprint in the snow along the power line — no one is going to know that looking at my work — and then there are the coyote footprints … Also, the predator — man — in the environment … We live in an unattached condo where the houses are really close together. In the back of the neighborhood, the builder took out five Mack trucks full of trees. That’s where the bigger home are going to go. It’s cheaper to take the big trees down. It just breaks my heart … I’m making the best of it … and enjoying nature; but that has had a big effect on me. It makes me very sad.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

Sometimes it’s a found object. I’ll find a rusted piece of metal, and it could be a skirt; or a muffler, and it looks like the body of horse. Sometimes my doodles will prompt an idea. Or, I’ll find a stick with a burl, a divot, a pattern created by insects that are so lovely I [see it] as an arm or a leg. Sometimes it’s just getting the clay out, and my thoughts lead me in one direction or another. I’ll pinch it, and it will look like something, and the whole thing that I planned changes.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

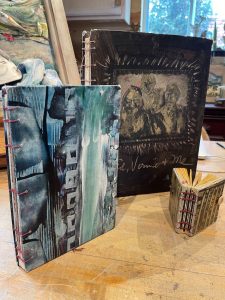

I’m going to be in a show in August about heroines.[4] I’ve been doing a lot of research and pre-planning for that. I’m looking up specific women in history who’ve led the way for all women … Right now I have sketchbooks filled with ideas for the heroines project, as well as names and ideas; but I’m working on all of the other pieces for my other galleries.[5]

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Yes. Always. I work in wet clay, creating enough parts to fill a kiln, and my kiln is out in the garage. While those pieces are drying and firing, I’ll be glazing another group of pieces. And when those are done,I begin the assembly process. That can take up the entire studio …

Do you work in a series?

Often, but not always. I find myself leaving a series, then coming back to it at a later time. I’m not sure why. Perhaps I think I’m done with a particular thought; but it keeps coming back in my doodles or play time.

It sounds like doodling opens up portions of your brain to new creative thought.

It does. I think that our sketchbooks are more telling about who we are rather than major pieces of work. There’s a rawness that comes out.

What’s your favorite tool?

My hands. My eyes. Even when I’m not working, I’m seeing on my daily walks along the power line, through the fields and the woods. Working in clay is all about sense of touch, being sensitive to the various stages of the clay — the dryness, the plasticity; it’s vital to the process. Beyond that, I have a tin of clay tools from my father. He was a sculptor and also a clay modeler at General Motors. He made his own tools in art school. I cherish them.

Your sketchbook is another valued tool.

I love sketchbooks. Because my mind can be scattered and I have a bad memory. I know where drawings and lists are in certain sketchbooks. I use them for recipes for glazes, vocabulary terms, for ideas, my imaginings.

How did you think about handwork before you began practicing seriously?

I don’t know that I really thought about it because I’ve always done it since I was a small child. It wasn’t anything I thought differently about. That’s why my hands are my favorite tool. I have to keep them busy. As an educator, I knew the concept of kinesthetics … Knowledge travels from your fingertips to your brain, and it helps memory and fine motor skills and problem solving. That’s not to say that working with computers or working digitally in the arts is a negative thing; but even the educations I worked with who taught digital arts — graphic design, photography, which became all digital — they would have the kids work with their hands as well, using a work journal, writing and drawing …

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

It’s my way of communicating with people. My words are not the best part of me. Working with my hands is my voice.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life? We’ve moved away from it. We’re computerized, and most “handwork” is keyboarding.

True; but I think we’ll come back to it. Just like we got rid of all the shop classes, the woodworking classes — they’re coming back. Our brains all work differently. Many children will be lost if they are only working digitally. Some of them will have an opportunity to have more growth, and be more intelligent if they can work with their hands … [Handwork] helps young people with their fine motor skills and it helps improve their brains and problem solving …

True; but I think we’ll come back to it. Just like we got rid of all the shop classes, the woodworking classes — they’re coming back. Our brains all work differently. Many children will be lost if they are only working digitally. Some of them will have an opportunity to have more growth, and be more intelligent if they can work with their hands … [Handwork] helps young people with their fine motor skills and it helps improve their brains and problem solving …

How do you come up with a title?

It varies. I collect names; the sketchbooks are a great place to store my collection of names. I find them on road signs, poems, in cemeteries. I used to live down the road from a small village cemetery in Goodrich. I wrote down all the interesting names I could find on the tombstones. Often a found object will have a name or number embossed into the metal, and that becomes a [title]. Also, just going on a map and looking at different places. [A “name”] could be a place. When a sculpture is a person or animal, it’s like having a child and naming that child. Sometimes the title is a commentary about what’s going on or a commentary about the piece.

What’s the job of a title?

The job of the title is for me to express what I’m thinking about that sculpture. For some people who see that title along with the piece, they may be affected by it because the title may have something to do with something that’s important to them, or someone who was or is important to them …

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

After art school [1983] I was in a slump. I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to say with my art, what I really wanted to do. Did I want to be a person in their studio working all the time? Did I want to work in a gallery and make my art when I wasn’t making money? Could I make enough money from my art? I couldn’t figure out where my next group of pieces were coming from. I didn’t have a printing press; but I loved to draw and paint. I wasn’t really much into the clay at the time. I received a gift from my father out of the blue [1984]. It was a box filled with menus and labels and newspapers, and postcards, magazine ads, et cetera. He’d kept all of them from the 1950s. They weren’t precious because they were scraps; but they held the key to something new, and I began a series of collages with them. And, drawings with Prismacolor pencils. They were small, very intimate little pieces. I made 30 of them, and I had a one-person show at Paint Creek Center for the Arts. It was the kick starter. That’s when I became serious.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I use it to stay in tune with other artists, to find competitions, and to share what I’m doing in the studio. I love podcasts. I really hadn’t listened to them until the [COVID] pandemic; but I found a few. Hearing other artist’s stories — they may not be working in the same medium I am; but I love interviews with artists as well.

What about Facebook and Instagram?

It’s a way for me to get my work out to the general public, and to receive comments back. Unfortunately, Facebook — there’s a small group of people I hear from. I don’t always get a whole lot of commentary back except for : That’s nice. Instagram — I’ve been able to have more followers and follow more people who I’ve learned from … I used to got to national clay conferences, and would meet famous people in the clay world, who’ve passed away now: Peter Voulkos, for instance. I felt so separated from them until Instagram and the podcasts, so I can actually see what they’re doing on a daily basis, and learn from them. I’m also taking clay workshops through ZOOM. It may not be something I’m learning a whole lot from, [but sometimes there’s] an a-ha! moment [that reveals] a great technique … Instagram, ZOOM, the podcasts: They’ve been educational for me more than they have been something that allows people to find my work …

What do you believe is the visual practitioner’s role in the world?

To share a passion and stay relevant. We’re visual storytellers. History has been told through the unearthed relics, paintings and sculptures. We are such a visual world. Visuals are everywhere, so if artists can be those storytellers, I think that’s a great education for the masses.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

The outdoors. It’s ever-present in my work.

You respond to world events in your work, too.

I’ll respond to that question with the piece Batsh.t Crazy. She pretty much is a reflection of how the world has affected how I’ve felt over the past four years. I’ve seen people who are batshit crazy, and I’ve felt that way. The constant news, the division. I’ve tried to deal with it with humor, more than anger. I did a couple pieces that were more like the [Edvard] Munch painting, The Scream, well. A little more serious, not quite so humorous. It’s gotten to the point I don’t even know how we’re all going to come together anymore.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s a constant. I’ve wanted to live here since I was a child. There’s something about the light, color, skies and the hills. I’ve never fallen in love with them like I have here. I love Michigan. And, I love Northern Michigan — that there are people who had the wherewithal, the money, the means and the dedication to create the different land conservancies, to make the Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes and national lakeshore so everyone can enjoy it. It’s very special.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place? How would we see this?

Absolutely. Many of my pieces have driftwood in them. I’m influenced by the color of the water and the grasses … And the ever present wind we have here. It’s those colors that I’m hoping find their way into my work.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan? Would your work have a different look or appearance?

Perhaps, if I lived in a city, and I was driving on the expressways, I think my work might even be less representational; but I’ve always been surrounded by nature. I’ve always loved it. So I think the themes are more intensified right now. Maybe it’s because I’m retired; I have more time to be outside.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

My father, Michael Tock. My dad worked with found objects … And he was a clay modeler [at the GM Tech Center] … I was surrounded by art. We had so many art books and his art throughout the house, and the artwork he’d bought early on in his career. I remember that I got called in by my kindergarten teacher because I was drawing naked women. My parents had to sit down and talk with me. And I said, I don’t understand. They’re all in the art books you have all over the house. I was very influenced by that. But also, by other artists — because my dad would take me to the DIA.

My father, Michael Tock. My dad worked with found objects … And he was a clay modeler [at the GM Tech Center] … I was surrounded by art. We had so many art books and his art throughout the house, and the artwork he’d bought early on in his career. I remember that I got called in by my kindergarten teacher because I was drawing naked women. My parents had to sit down and talk with me. And I said, I don’t understand. They’re all in the art books you have all over the house. I was very influenced by that. But also, by other artists — because my dad would take me to the DIA.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I would say my dad; but also children books. Those illustrations, those fairy tales. …. My parents were very different. My dad, the artist. My mom, the educator, who loved books. She loved to weave a story. In my quiet way, I fell in love with the two personalities of my parents as seen in those children books and stories — the drawings in them and the tales being told. I could live in my own little fairy land.

How did your father nurture your creativity?

He would be my biggest critic, and it was the best things ever. He wouldn’t say, Oh, that was a pretty picture. He’d truly talk to me about what needed work, and I needed that honest criticism. If he wasn’t sculpting, he was always drafting ideas for homes, or building things.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My husband, Ed York. But I do have a dear friend who is a fiber artist, and we will text images back and forth for honest opinions. I did belong to an artists’ critique group when I first moved here, and we’d gather once a month. That was very helpful.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

It’s my opportunity to have an audience. The process of making is more important; but exhibiting is an honor. It gives me a chance to use my visual voice to share my story, and hopefully strike a chord with the viewer. When someone purchases my work through an exhibition, it means a great deal to me. I appreciate that they’re willing to spend their hard-earned money on art …

Did your teaching cross-pollinate with your studio practice?

Yes. My mantra was: Practice what you preach. I was an artist-educator. I would bring my work into the students … We would critique their work, and they would critique mine as well. I would bring my [advanced placement] students to Goodrich. I would show them my influences and my studio. And take them to Flint Institute of Arts. I had a lot visiting artists come in as well. I would let them see the life of being an artist. I also thought the kids influenced me. We learn so much from people of all walks of life. Teachers don’t know it all, for sure. We learn from our mistakes. One of the reasons I didn’t want to become a teacher in the beginning was that I was terrified that I might say the wrong thing, and a child might not like art anymore. I felt like they didn’t all need to be artists; but they needed to work on not losing their imaginations and understanding the art world …

Were there challenges to doing your own artwork while you were working outside the home?

Yes. I was tired a lot. You get lost in your studio space, and next thing you know it’s 2 am and you have to be up at 4:30 am. It was more of a challenge raising children [6] and teaching full-time and being an artist. As those times became more difficult, and getting a higher degree at the same time — I don’t know how I did it all — that’s when my sketch books came into play. I knew I had to be creative in some way. I couldn’t just set it aside. So, the sketch books are where I put all my creative energy. I still go back to those. If I’m stuck for an idea, I still have those drawings and doodles to bring out inspiration.

Footnotes

1: Michelle taught visual art for 30 years in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in both middle and high schools. She retired in 2016.

2: Michelle also received a Masters in Humanities from Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan in 2000.

3: Michelle’s “littles” are “are my collections of small items such as miniature antique shoes and old hardware (nails, screws, hinges, etc…).

4: Heroines – Real and Imagined, at Higher Art Gallery in Traverse City, Michigan. The dates are August 6 – September 5.

5. Michelle is represented by Higher Art Gallery; Sleeping Bear Gallery in Empire, Michigan; and Twisted Fish Gallery in Elk Rapids, Michigan.

6: Michelle and her husband Ed are the parents of two children, 31 and 27. Between 1993 and 2011, Michelle was dividing her time between parenting, professional work and her studio work.

Learn more about Michelle Tock York here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.