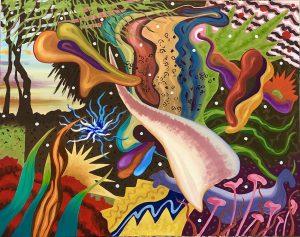

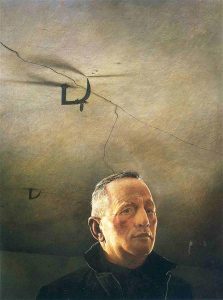

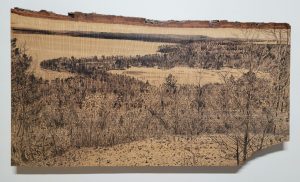

In addition to everything else in his busy life, Nik Burkhart 38, maintains a studio practice focused on painting, drawing, making marks on wood — as well as on the usual suspects [paper, canvas]. “I’ve been drawn to working with wood because it allows me to engage directly with a natural material, and embedded in that material is a history of growth and the history of another living thing,” he said. Here’s Nik’s history, and the events that have embedded themselves into his fiber. It’s the story told in the growth rings of a married guy with two kids, two day jobs who has been focused on doing creative work since high school.

This interview was conducted in May 2025 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Nik Burkhart standing next to his 2024 mural Wiigwaasi-iimaan: A Mural For The Fouch Trailhead, a digital print on aluminum composite panel, 4′ x 16′.

Describe the medium in which you work.

Primarily painting, drawing, and I incorporate wood into my artwork.

Although you create work on traditional surfaces [e.g. paper and canvas], so many of your works are done on gessoed wood [e.g. plywood, Red Oak, Cherry]. Why wood?

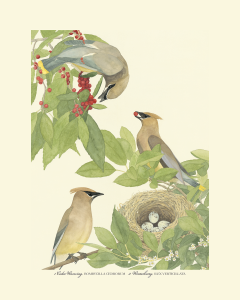

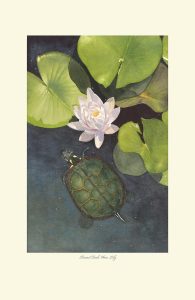

I’ve been drawn to working with wood because it allows me to engage directly with a natural material, and embedded in that material is a history of growth and the history of another living thing. It becomes a conversation with nature and the natural world. Directly. Especially if you think about how a tree grows, and how it forms its growth rings and grain. Those are interesting things that bear the history of how the tree grew, how it was harvested and milled and brought to market.

Sometimes you gesso the wood’s surface. That’s a way for you to use drawing and painting materials that will be compatible with the substrate. Do you ever let the grain and the wood’s natural surface be part of the composition?

Absolutely. I like to play between those scenarios. For instance, if I’m working on plywood I’ll need to do a gesso priming just to make the surface ready to accept additional media [paint, charcoal, graphite]. But I do enjoy, in other scenarios, putting Urethane or directly working on the wood before any other intervention, to allow the wood grain to inform the decisions and the composition I make.

In the painting world, there’s lots of talk about creating layers. Underpainting is a good example of this kind of surface enrichment. When working directly on wood, it makes me wonder if the same kind of layering-thinking comes into play?

Yes. That idea of underpainting and imprimatur is an interesting thing to me, especially as it connects to painting. I think it ultimately calls the artist to have a sensitivity to the materials they’re using, and how you can think strategically about how to incorporate that into the overall, finished project. A lot of times, it can be an intuitive thing; it doesn’t have to be explicitly decided upon ahead of time. Sometimes I’ll think I’ll want to incorporate the wood grain but then realize it’s not working the way I thought it would. The nice thing about wood is that you have the option of carving back into it. I like working on canvas, too; but if a composition isn’t working at a certain size or shape, you can reinvigorate it by cutting it or sanding away [but] it’s harder to do [than with wood].

Yes. If you sand the canvas too much, you’ll get a big hole.

Which could be interesting.

How did you start using wood in your practice?

I’m a thrifty person. I like to reuse materials that otherwise would be thrown away or discarded. A lot of my work on plywood started when I lived in Chicago. I worked for an art handling company; we would fabricate and pack art into crates using plywood. There were a lot of smaller scrap materials leftover from the process of building crates. Those would often be thrown away. I’d waylay those from the dumpster, and use them as painting surfaces. The same thing in an art supply store would cost significantly more. I discovered quickly that I could get a comparable product for free. Some of the paintings from the time I was working in Chicago were actually done on old crate lids, or parts of crates we broke down. That’s how it started. Since moving here, I have access to my father-in-law’s wood shop. He has a lot of spare cutoffs and odd-sized boards that would be hard to use in a larger project. I do love the idea of wandering through the woods to find pieces to work with, but it has typically been the case where what has already been milled is what I use. I’ve started to get involved with the process of milling.

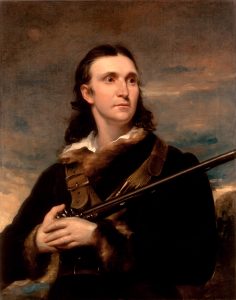

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

I have a bachelor’s degree in studio art from Hope College [in 2009]. I also took classes as a high schooler, and have benefited from that formal training. I would have liked to have studied, more specifically at an art school, for further training. But, ultimately, the [training he did receive] gave me a framework to learn, especially from art history, and to look at the work of other people to expand my own practice. While I was at Hope, one of the formative experiences was [participating in] a satellite campus they had in New York City, working with an artist [Chris Anderson], and taking studio and art history courses. That exposed me to types of art I wouldn’t have seen, and contemporary art history that opened up a lot of new frameworks of understanding about how I could approach my own work.

It also got you out of the classroom, and directly experiencing a person who practices visual art as their job.

That was helpful because it showed me what was possible. It showed me that it was hard to be an artist. It hasn’t been a linear [educational process]; but it has contributed to where I am now.

Describe your studio/work space.

I have two studios: a winter studio, which is in the basement, and a summer studio in my father-in-law’s barn. The barn doesn’t have heat, so it’s not convenient to be in during the wintertime; but it is a great to have access to a full wood shop with power tools. I have a desire to have a year-round work space; but you need to start somewhere. Waiting for the perfect set-up, fixating on your studio or lack thereof, you’re never going to start.

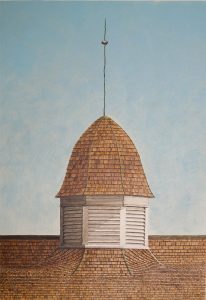

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

In a lot of cases, my work deals with a history of choices, a history of place, the way the choices — either my artistic choices or in the process of making — accumulate over time. Coming back to this area where I grew up has challenged me to re-explore and reexamine my connection to place and landscape, and go deeper into understanding why things are the way they are.

What does that mean: “… why things are the way they are”?

I’m still trying to figure that out. What I mean by that is trying to get a deeper understanding of the history that’s embedded in our current experience, how or why land looks like it does, what do we use land for, how do we interact with each other because of those historic choices. Also: the various technologies we use, that shape our lives and how the world looks around us. Part of that connects to growing up on a farm [in Brutus, Michigan]. It was a 100-acre farm that my dad worked full-time; but he also worked elsewhere to support our family. It gave me a connection to the land, and an appreciation for working with the natural world. I spent a lot of time on the tractor bailing hay, stacking hay in our barn.

What’s your favorite tool?

I love sand paper. It’s amazing what you can do with sandpaper or a sander. I use a random orbital sander. When you’re working with wood, it allows you shape the wood — both smoothing it out, and sculpting it. I use it like a carving tool sometimes, if I’m sanding back into the wood. It allows for a lot of versatility. It’s funny that for a painter or drawer that sandpaper would be [his favorite tool].

You’re not letting your designation as a painter define your tools. You’re finding the tools you need to use to do the job, to create the result.

Yes. You were talking earlier about underpainting. There was an idea I came across when I was in school: palimpsest. Essentially, these ancient manuscripts would oftentimes get cleared, so layers of text build up, and over time come to the front. What I like about that is there’s a history of the object’s materiality, that those things — even the things that aren’t immediately visible — still influence the outcome or the final object or the history of that object. Similarly, in my artwork, I think of them not just as images. I carve sand back into it to reveal the history.

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

Making by hand allows my own artistic tendency to come through. Over time that becomes my mark on my artwork. Like it or not. I think very tactile-ly. We’re all physically embodied to make and create, and working by hand is one way to celebrate that. I like how working by hand filters [the object] through my own experience. It can become a contemplative action that’s helpful for me personally.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life?

It helps me to be present. There are so many ways where our attention is drawn elsewhere. In that way, it has a lot of positive emotional benefits, and can be one of the benefit of artistic process — not that it necessarily has to be a therapeutic outlet. If we can be present with ourselves, we can be more present with other people.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances that were the backdrop to that decision?

There have been defining moments. In high school [in Pellston, Michigan] I had always had an art class. I got my schedule and didn’t have an art class for that particular semester, and I wanted an art class. So I wrote a letter to the principal saying that I was thinking about exploring a career in the visual arts, so I wanted an art class to continue on that trajectory. I got an art class, an independent study; but that process of stating the idea was helpful for me to make a commitment. Since then, there have been other defining moments, other choices to follow through. A project that was helpful to me to gain the confidence needed was, as a freshman in college, I was commissioned to paint a mural in the Emmet County Fairground in Petoskey. It was a great experience, that they would have trust in such a young artist without a proven track record. Financially, it was great compensation. It encouraged me to see that there are ways to make the arts a viable, professional option. There is a necessity, honestly, to work outside the arts to support myself and my practice; but those experiences and studying art helped me to commit to that trajectory, that commitment to an artistic practice.

What role does social media play in your practice?

It doesn’t play that big a role in making art. I use it as a way of seeing other people’s work, a way of fostering community and connection with other artists. I’m somewhat wary of social media. I don’t completely understand the implications of algorithms and AI. Honestly, I don’t spend a lot of time scrolling and Zooming. It can exhaust energy I could use elsewhere. I have a complicated relationship with it.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

I’m still trying to understand that. At some level, we have the ability to make visible things that aren’t immediately visible. In some ways, artists have a responsibility to draw attention to social issues. But there’s value in just being able to appreciate beauty in the world — as well as being able to take the temperature of the cultural moment. Artists can also give voice to things or ideas or people that wouldn’t otherwise be heard.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

Having grown up in Northern Michigan and being surrounded by the natural world has informed the things that I care about. When I was living in Chicago [from which Nik moved in 2021], architectural, built things played a role in the work I was making at that point. Being back in Northern Michigan has reinvigorated the connection to nature, and the emergence of natural themes in my own work.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice? Someone who modeled what it looked like to be a working artist?

There have been a lot of artistic influences along the way. My mom modeled creativity in a way that gave me access to the idea of making things. She has always quilted. I grew up in a Mennonite community, and they’d have quilting days twice a month. I got to go and hide under the quilts. I was the kid underneath the table. It was cool seeing people coming together to work on a shared, community project. I often come back to that when I think about creative community, and think about the way ordinary people can work with ordinary materials to create something beautiful.

In quilting histories, there’s always a mention of somebody’s kid sitting under the table while their mom is quilting. Finally, I get to meet somebody who was really that kid.

I’d throw my stitches in sometimes, too. My mom and I have talked about collaborating on a project. Having those contexts where I can learn and gain knowledge has been helpful for me. A lot of my other, artistic influences were my instructors in school. They had enormous impact on how I thought about art. Katherine Sullivan was my instructor and advisor at Hope College. In Chicago, an artist who was also a teacher at North Park University, Tim Lowly, was an informal mentor for me. I appreciated how he fostered community within the context of the academic college community; but how he, even now, gave a platform for artists to share their work with a larger audience.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My wife, Theresa. She knows me well and isn’t afraid to pull punches. There are other artists who I go to from time-to-time. In Chicago, one of my most informative feedback communities — we called ourselves The Group Format. It was a group of six or seven artists who were serious about making art. We’d meet every other Saturday, talk about each other’s work, and give feedback. That was incredibly helpful to me. It helped me move forward in my practice. That was at a time in my life when I was working in property management, so I didn’t have that much incentive to be making work as my day job. It was a way of still feeling connected to that part of who I am. I’m still finding my people here. Those things develop overtime.

I was looking at your website, and at the page where you list exhibition history. You graduated from college in 2009, and dove into exhibiting – both solo and group shows. I counted 51 exhibitions on your CV. So: Question #1 — What is the role of exhibition in your practice? And, Question #2 – You’re married, and the parent to two small children. How do you carve out time to make work so you can exhibit?

I was somewhat surprised by the number of exhibits that I have had. My exhibition list is something that I often feel self-conscious about in the sense that I would like to have an even “more prestigious” list of venues and institutions. I think artists often undervalue the legitimacy of our own history and easily fall into the trap of comparing ourselves with the pedigrees of other artists. Taken as a whole, my exhibition history communicates a feeling of a trajectory; but what it doesn’t show is the level of self-doubt, frustration or disappointment when I have been turned down for shows or go a while without having a significant opportunity to show my work.

For most of my artistic career, I have primarily exhibited my work in educational spaces, art centers or non-traditional project galleries while working in other jobs to support myself financially. This has allowed me time and space to develop my artistic practice with limited commercial pressures. I have only recently begun to have more interaction with commercial gallery contexts. Exhibitions have been helpful for the deadlines (and the ability to call something “done” and all the things that I talked about in the interview) and the opportunity to more objectively see and assess the impact of my artwork. Themed shows and call for entries allow me to explore new territory or mediums that I wouldn’t ordinarily use in my practice. It’s also a great way to connect with other artists and invite people in to see what I have been working on. Exhibiting helps me to feel part of a larger community. The process of writing about my artwork for a show statement allows me to hone my vision for my work. I often learn as much from hanging a show (especially a larger body of my artwork) as I do when I’m making the work. Because my studio space doesn’t allow me to hang large amounts of work together, it often isn’t until I see it in an exhibition context that I realize the larger conversation that each work contributes to.

Back to Question #2: There are two little girls to whom you’re the father. You have work you do outside the home. There are lots of things that require you to be present. How do you find time to be present with your own work?

At its best, being a parent is a creative practice as well. There are times when the creative practice of being a parent has to take over my artistic practice. From a productivity side of things, I could probably make more work if I didn’t have other commitments; but I find that the creative practice of being a parent, being in a relationship with my family fuels and expands the world, it energizes my artistic practice instead of competing with it. There are time management challenges. In this area I’ve really benefited from Theresa’s support. My in-laws have also been instrumental in caring for our kids as well. That has allowed us the space to live the way we do right now.

I like how you framed that, talking about the experience of being a parent as creative work. It makes me think about how all things are integrated. It’s not just about parceling things off into a bunch of unrelated silos. For the person, for instance, who wants to be a writer, you just can’t sit in your room and write; you have to be out experiencing the world. What you’re saying is that everything fuels the next thing, and the thing next to it.

I framed it in an idealistic manner. The reality is there is that tension that makes it feel like a competition. When I have the space and time to work, it means somebody else needs to take care of my kids. That’s something any parent needs to navigate. But it’s also fun to have my kids involved in my making. Sometimes I allow them to paint on top of something I’m working on. Or, I’ll put out materials and supplies to let them paint or draw, as a way of entertaining them. Sometimes I’ll use their drawing as the foundation for my own work. Their paintings will be on the back of my work, or I’ll layer over with my own Capital “A” artwork. I’ve had to recognize the time I do have to be creative … and pick the work I need to do based on the time I do have available.

You have a day job.

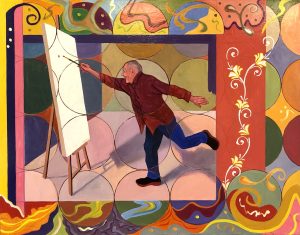

Currently, I have two day jobs. I teach oil painting at Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City. I started that in the fall of 2024. Day Job #2 is I’m working as a studio assistant part-time to Jerry Gretzinger in Maple City [Michigan].

How do your day jobs cross-pollinate with your studio work?

Having had plenty of other day jobs — from the time I graduated from high school until now — sometimes it’s like the emotional fuel. Sometimes the day jobs have conflicted with my desire to create, so creating from that place of angst is where my work has come from. Sometimes the effects of the job don’t manifest themselves immediately; but I believe there’s no wasted experience. One way my job at NMC has manifested itself in my current practice: I’d stepped away from oil painting because of the solvents, and the chemical and spatial requirements — I don’t want to be using toxic chemicals around my kids, so I shifted to drawing or using acrylic paint. The NMC program shifted to a solvent-free approach to oil painting. So when I was hired, I had to relearn how to oil paint without the solvents. That has shifted some of the material choices I have made, and I’m painting a lot more with oils because of my day job.

What drives your impulse to make?

I’m a firm believer that we all have creative capacities. I think I have this creative impulse I’m trying to steward. I’m trying to make things and offer that to other people. At a very basic level, that’s why I do what I do: I really enjoy it and hope that other people can participate in that. There are times when I’m not making art or working in some other creative outlet, I feel stuck. Emotionally, it makes me a better person to be making things.

Learn more about Nik Burkhart here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.