Creativity Q+A with Kaz McCue

Kaz McCue’s lives as an educator, studio artist, and regular-guy-walking-around-the-place blend seamlessly into one another. Everything is connected. Everything cross pollinates, whether it happens in the studio or the classroom. The 59-year-old Leelanau County resident works in many media, unconfined by a single material or technique. As a art student in the 1980s + 1990s McCue learned about being an artist-citizen, and the concept became a guiding principle. The work of a studio artist, he says, is more than “putting on your smock.” It comes with some responsibilities. This is what he lives. This is what he teaches. This interview took place in February 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

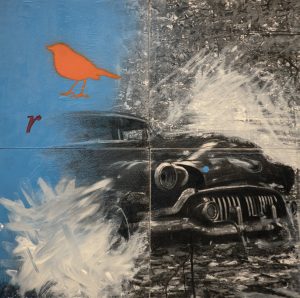

Can’t do it. That’s one of the most basic questions for an artist, and it’s one of the hardest for me to answer. It took me a long time to realize what my place was as an artist, and that was a visual storyteller. As I was coming up through school and working as an artist … I meandered through disciplines, and it took me a long time to realize what I was about as an artist was storytelling. Sometimes my stories needed etching. Sometimes my stories needed photographs. Sometimes they would need sculptures, video. As an artist I don’t box myself into a corner with media. One of the constants through my work is my approach to the photographic image. I have a Bachelor of Fine Arts in photography, and I studied in a very traditional program at Parsons School of Design [1988]. I had very formal training there. And, I love photography. Artistically, I wanted to find more. Because of that traditional training, I was having a hard time experimenting with photography. I found my way out of that corner in grad school. I found a printmaker who was really interested in alternative photographic printmaking techniques … That opened up so many doors, and I’ve stayed on that path. Every time I got stuck, or had an idea I didn’t know how to approach, I’d turn to new media … I’ve probably spent the first half of my career putting tools in my tool box to the point now I’m skilled in a lot of different areas, and I can meander around.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I would say less so than my experiential training. From the standpoint of studying, I put myself in really good spots to learn what I was interested in learning. I was more interested in an individual path than a commercial path. My education was more about the people that I connected and studied with. At Parsons there were an incredible number of professional photographers and artists, and in the 1980s New York was the center of the art world. I was in the middle of it. It was definitely people who mentored me along. [NOTE: Read Kaz’s curriculum vitae here.]

Formal training put you in touch with people who could mentor you?

Yes.

Describe your studio/work space.

I have a parasitic work practice. I’m comfortable working in big, well-equipped workshops, and I’m equally as comfortable working at my kitchen table. I look for opportunities to do the former; but the reality is I spend more time at the latter. Through my career I’ve always found spaces to work … Every time I get a studio space, I fill it with junk. Being parasitic allows me to be a little more fluid. I have the studio at [The Leelanau] school [where he teaches] that I can use on breaks if I have a really big project — I have a 6 foot x 6 foot drawing hanging up in the studio at school right now. My studio is kind of anywhere I’m at. I’ve got a set-up here at my house here in Michigan. I’ve got the art studio at school I can use. I’ve got our house in Florida, which is where my wife [Pamela Ayres] lives and teaches. I’ve a small space down there — oddly enough, I prefer to work on the porch … With my background in material culture studies, I wasn’t working in a clean, white space, like a painter would. I was climbing into dumpsters, and junk shops, and finding inspiration all over the place. It seemed silly to take it out of context.

If we go back to the question about medium — one of the things I do spend a lot of time with is concept. My ideas and what I’m focused on come out in symbols, and concept and context. I feel like my work has a vernacular quality to it. I think it’s because I don’t need anything fancy to make it work. I can do something as simple as a drawing or complicated as a room-sized installation. And depending on the story, I’ll find the space. Right now, with the spaces I have available, I’m pretty comfortable. The shutdown from COVID, and having a lot of alone time was really studio time for me. My studio is where I make it.

Define material culture studies.

It’s a sociological term … The study of material culture is looking at the materials and the objects that a culture uses to gain insight into that culture. For instance, we can look at a chair, and a chair can have a lot of different meanings: from very basic, functional, sitting-down to an annotation of power, or [a symbol of] missing somebody. You can read a lot into a chair … Materials come with inherent meanings that you can then start to play around with. You’ve got pieces of the puzzle that already have some meanings in them. When you recreate new relationships, it expands that. With material culture studies, there’s a pretty straightforward methodology to studying objects, to go from straightforward observation to inference, which is the educated guess you make about the culture. That methodology gave me a platform to build stories … Material culture studies also feed into [his] background in photography. At a certain point, photographs become a cultural object as well.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Well, I’m approaching 60, and a white man in a country that is incredibly confused and divided. Politics, to a degree; but I don’t like those layers to be out on the surface. I’ve been spending a lot of time, in the last 10 years, talking about migration as I’ve become more interested in my own history and background … I’m 100 percent Irish. We came over as skilled labor [in the 1800s] … Death, obviously — I’m getting older. I had a wild path. I never thought I’d make it to this age. I’m probably 10 years shy of when my dad passed away. Maybe not death so much as mortality. I don’t trumpet themes. I inhale them and chew on them a little bit, and put them out there … The things I’m interested in discussing are buried underneath the layers. You have to peel back the layers to get to [the theme, meaning]. That goes to my own approach [to looking at art]. I like artwork that makes me think. I don’t get excited about artwork that spells everything out for you. It doesn’t mean I don’t like that stuff. It doesn’t get me as excited as something that makes my mind work; where I have to figure out what did the artist mean when he did that? Did he mean this? Did he mean that? I play that game with my own work sometimes: Did I mean that? Did I mean this?

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

I see it all as a process. Ideas percolate, and come to the forefront. Other times, they just pop up and move to the back. Right now, I’ve been in Leelanau County for 10 years-plus. I really love it here: I love the seasons, the lake shore, I love Port Oneida [which is] way up there in my focus right now. I’m spending a lot of time crawling around Port Oneida, learning about its history, and thinking about what the place was and what it wants to become … This is years coming. I’ve spent a long time working on Port Oneida as a subject. If we go back to material culture — the barns and the sheds, and there’s even a conversation between the way the farms are laid out — it’s very Eastern European in some cases. I love that history. I love walking those properties, and imagining the people who lived there and made the land work. That has inspired another project, which is four years down the road. Through the process of working, I’ll do one piece that will be, like, Ooooooh, that’s really different. And, I’ll like it; but it doesn’t fit in what I’m doing now. So that piece will go over to the side … Some pieces come really fast. Some pieces come with opportunity. I had an opportunity to do an artist’s residency a few years ago at Villa Barr Art Park in Novi [Michigan]. I’d been thinking about the Irish diaspora. And, I’ve been doing theseboat forms, and all of a sudden I had this chance to explore these boat forms. I ended up doing a sculpture for the park.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project?

In my mind I do a considerable amount. I’ll kind of sit on something, and think about it …. I should go back to talking about my studio practice. In my practice, I tend to binge. So, when I get time, I work intensely to the point where it’s hard to think about anything else. I give myself blocks of time …

You’re very organic about your process. One thing gets started; but there may not be a distinct end to it — you seem to stew, and germinate and muse about things.

In grad school I got to study under Noah Jemison [at Long Island University/C.W. Post Campus]. Noah was a fantastic painter. He lives in Brooklyn, has been part of the New York art scene since the 1960s. The faculty saw the opportunity — they had to have him work with some of the grads. Noah came in and worked with a lot of us. He mentored my wife and me. Noah used to drive me nuts. I was very organized. I had the studio, and I was making a lot of work, and he’d come in to do critiques, and he would never talk about my work. The conversations were, “Hey! Did you see that basketball game last night?” It used to frustrate me so much. One time I got so mad at him, I said, “Look. I’ve spent all this time making this work. The least you could do is talk about this work.” And he said, “Why would I talk about this work? I’m still trying to get to know who you are … I see that you’re making a lot of stuff that looks like art; but I’m trying to figure out if it looks like your art.” And that just messed me up. But he taught me that being an artist was more than putting on your smock and working in your studio. He taught me that being an artist was being an important member of the community. He taught me that being an artist had cultural responsibility. He taught me that being an artist meant being a leader in the arts in the community wherever you can find it. And he taught me that whole idea of being artist citizen*. That just blew my mind. My practice is organic, and it is strongly connected to my life. There’s no way I can separate my art practice from my teaching from my politics from the way I approach community. It’s all wrapped together, which is what Noah was trying to teach me to begin with: Figure out how to make it part of your life.

*Follow-up | Kaz writes: “So, Noah always talked to us about what it meant to be an artist. He would tell us that in order to be an interesting artist, you had to be an interesting person. In the United States, we have a lot of artists who study in college and are well trained; but what Noah was getting at is that it was important for artists to hold a place in the world and then express, reflect, philosophize about that world through their creative work. In other words, it was not healthy for artists to work in isolation or seclusion, and it was important for artists to be a part of whichever community they chose to exist in. Noah stressed the idea of community and how necessary it was for artist to function with the community as contributing members.

“Later, in 2004, Joseph Polisi, who was president of Julliard College, wrote a book titled The Artist as Citizen. In the book he write: ‘Artists of the 21st century, especially in America, must rededicate themselves to a broader professional agenda that reaches beyond what has been expected of them in an earlier time. Specifically, the 21st-century artist will have to be an effective and active advocate for the arts in communities large and small around the nation. … By performing superbly in traditional settings and making the effort to engage community members through their artistry, America’s best young artists can positively change the status of the arts in American society.’ ”

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Yes. I won’t talk to you about how many I’ve got going now. It’s hurting a little bit.

Do you work in a series?

Yes. I binge work. It seems like there’s also a dialogue between the pieces I’m doing at the same time, when I’m going back and forth. I’ll get done, and I’ll think, “That one’s really saying something. That one’s not,” and I’ll not finish it, or move it to the side. When you’re writing a story, you do edits. I’m doing the same thing … I like to feel like I’m living the postmodern life, and that’s just part of it, having all these little tributaries that you can meander down. And, if one doesn’t work, you can come back and go in a different direction …

What’s your favorite tool?

Definitely the arc welder. I love welding. I started with ceramics — very tactile. And then I went to photography. And then I went to printmaking, and sculpture. But when I got to sculpture, that practice matched my personality. I love teaching it, too. I love welding because there’s a sense of power to it, and also a sense of immediacy to it. You can have an idea, and see it right there.

It’s a high-powered gluing machine.

Yes. You have a piece of metal, you stick it on there and look at it. If you don’t like it, you can break it off. When I was working on that piece for [Villa Barr], I worked for two days straight, and I was going nowhere … I called my wife, who’s probably one of the people I get the best feedback from, [and told her], “This thing’s a disaster. I don’t like it. The form isn’t right.” And she said, “What would you tell your students to do?” And I said, “Cut it apart, and start over.” So, I cut it apart, and started over. You have that power with welding. It’s like drawing in space. I love that. You get to see something three-dimensionally, that interacts with space. And, I love that I can [make] something as big as me [5 foot, 6 inches tall], or bigger than me, and it stands on its own.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I’ve got them laying all over the place.

How did you think about hand work before you began practicing seriously?

I was raised in a middle class family. My sister and I had art lessons. We both went to Catholic school. Catholic schools didn’t have a lot of arts programming. It was instilled in me that I have to study hard, and be good academically, and art was fun; but it was not what was going to build my life. My mom was a corporate executive in the ‘60s [a vice president with Swiss chemical giant Ciba-Geigy], so she pushed hard for us to do well academically. So I had a different trajectory. I was going to go to school and become a veterinarian. And then my dad passed away my senior year, and that put everything in a twist and my life unraveled from there. So, for me, working with your hands — I was torn over it … My dad was a self-employed roofer, always worked with his hands, and that’s what I thought about hand work. And my mom, who was a white collar worker, who was very successful, and very powerful …

It sounds like, in your family, brain work was the highest-level work, and hand work was something that had practical usage; but it wasn’t what one should aspire to.

Yes. Because of my dad’s work, I had access to hammers, and saws, and nails. We built tree forts. We built jumps over my mother’s azalea bushes. We built go-carts. We did all that stuff; but that was for fun …

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

I’ve had the opportunity to work with kids with disabilities. They’re following careers [of disabled people] like Chuck Close, who has that terrible stroke, and came back to have a really remarkable last portion of his career. I’ve often thought about what happens if I couldn’t make anything by hand, and the thing is it’s an important part of my identity, like it was for my dad. I’ve spent a long time trying to get closer to my dad by being more like him. He was very soft-spoken. Never raised his voice. Never got mad at me, no matter how stupid I was. He was kind and sincere and a wonderful person. I hope I’ve been able to become more like him … [Making-by-hand is important] because it’s who I am. If I lost that ability, I’d be a different person. I’ve thought about it because of working with people who’ve had to deal with it, and I know I’d be able to figure it out, but I’d be a different person.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life? Or, not?

[Kaz holds up cell phone and pantomimes tapping the keyboard.] This is not working with our hands. I try to tell my students that all the time. That’s working with a funny little rectangle and exercizing your fingers. There’s a reality to hand work that you just can’t replace … We have two lobes to our brain, and if we’re going to be human beings, and good human beings, we want to exercise both parts of our brain. If we live more on the left side of our brain — if we’re an accountant, or doing high-functioning math on a daily basis — we need something to put us on the right side of the brain … Brains need to be in balance, and that cross-over is really important … When I talk with my students about this, I talk about observation. When you’re sitting there with a piece of paper and a pencil, and you’re looking at something and drawing it, you’re doing direct observation. You’re observing things you can’t get in a photograph. And you can’t replace first-hand observation. You can look at an orange all you want on your phone; but until you actually peel the rind, get a little zest sprayed in your face, it’s a different experience.When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

I’ve had two points in my career. The first was when I was at Parson, and I was working for a still life photographer in New York. Another wonderful individual who towed me along. A great guy. He took me in. I was his first, full-time assistant in his studio. We were doing ads for American Express Platinum, Scalamandre fabrics, and Shaw carpets. He did a lot of work for Interiors magazine. One day he brought his portfolio from his thesis show, and I was looking at it, and said, “You’re really an amazing fine art photographer. What made you decide to go into commercial photography?” And, it was very simple. He said what he wanted from his life was to make a nice living, get married, have a house, and have a family. He had a similar experience like mine: He worked for a commercial photographer in Chicago, gained that experience, and decided that was the direction he wanted to go in. That was my first real lesson: Make a decision. If you want to be a commercial photographer, and make money, and have things, you have to understand you’re providing a service. You’re not making art. You’re providing a service. If you’re good with that, you’ll be happy. But if you go away thinking you’re an artist, and the client thinks you’re providing a service, then you’re going to be unhappy. On the other hand, if you don’t want to work for someone else and do what they want, when they want, on their timeline, then fine art photography is great way to go. I decided, based on that conversation, I didn’t want to have anybody tell me what to do … Having the wherewithal to make that decision also meant I had to give up the semblance of making money …

And then I met Noah, and Noah taught me about community. While he’s teaching me to learn who I am so I can understand my art better, he helped me to understand who was my “audience” — and it was my colleagues and professors at in the grad program at C.W. Post — he helped me to realize I didn’t really like that audience. The people I wanted to speak to were my friends, my family, and the people who would always come to my art show, and say, “This is so amazing. I don’t understand what any of it is, but it’s awesome.” Those are the people I want to understand, to connect with, to tell stories to. That’s were material culture [studies] started to creep back in. I realized I could use objects, and that would give people a way in. Things started to fall into place.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Not much. My work, to a certain degree, goes against technology. One of the themes I have worked with throughout my whole career is the deconstruction or decomposition of photographic images. When I was studying in New York, there were a couple of guys who’d graduated from the School of Visual Arts, Doug and Mike Starn. They were superstars in New York in the ‘80s, and they really took the idea of a photographic image to another level. They cut it apart, taped it, and glued it, and nailed it back to boards. They didn’t care about archival-ness. So I got to see some cool stuff; but I’ve loved that whole idea of what is a photographic image? From an historic and artistic standpoint. There’s a lot of hidden stuff to photography. A lens distorts reality. It manipulates it. And when we’re in the darkroom or working on a computer, we manipulate it some more. When we look at photographs, we tend to accept them as truthful information because of our visual culture. The thought of social media and imagery weighs on me all the time. If you get a group of 100 people together and ask how many have painted, you might get, maybe, a quarter of them to raise their hands — if the odds are high. But if you asked them if they’ve taken a picture, 100 percent of them will raise their hands. Everyone has taken a picture. What’s changing is the codification of visual imagery in our culture — because of social media. And, technology. When George Eastman came out with the Brownie camera, you paid $25 and you got this camera with 100 pictures in it, and you shot pictures of your world. You’d send it in, and they’d send it back with a new roll of film in the Brownie, and you’d start all over again.That act of bringing photography to the masses had a huge impact on our culture. Look! Here’s a picture of the new cow, let’s send it to Johnny who’s in college. Now everybody has a phone in their pocket. Everybody. And, we treat images very differently. Images are almost becoming more codified than language at this point … I’m really more interested on the effect social media is having on culture, than the social media itself.

What’s social media’s influence on the work you make?

I don’t know if I’d say it has an influence … I like looking through old books. I have a lot of old books. That’s what the sketchbooks are for: it’s a place to collect ideas and images, thoughts. That becomes a place for sourcing. This came about as working as [an educator]: We don’t talk about sketchbooks. We talk about them as source books. That terminology — at least, working with students — has given students the permission to put anything [in the sketchbook]. They can say, “I don’t sketch, so a sketch book isn’t important to me.” But, you need a place for your ideas.

What do you think is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

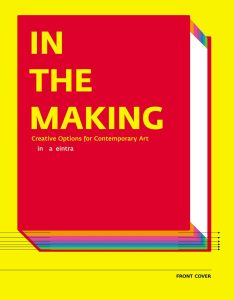

Years ago my friend wrote a book called Creative Options for Contemporary Art. I loved this book, and I learned a lot from it … It talks about universal concepts for creative individuals: Understanding your audience. Sourcing inspiration — where do your ideas come from? What is your artistic attitude? As I alluded to, my artistic attitude is that of a 50-something-year-old, pissed-off, American white guy. What is my approach to my work? I take the approach of an interpreter. I like to interpret, recreate relationships. One of the other things: What is your mission? It really depends upon what your mission is as an artist? Your mission may be to paint pretty pictures, and that’s a great mission. And then you figure out how you measure success against that. My mission is to be a storyteller. So I measure my success against that by how many stories I can tell that connect to people … When you making stuff, if your mission is to be a storyteller, you measure your success on how well people can engage with that story. In some cases they may just engage with it for entertainment. In some cases they may engage with it for intellectual stimulation. In some cases they may engage with it because of the material connection. There’s a lot of ways to approach that. That becomes a very individual question.

Years ago my friend wrote a book called Creative Options for Contemporary Art. I loved this book, and I learned a lot from it … It talks about universal concepts for creative individuals: Understanding your audience. Sourcing inspiration — where do your ideas come from? What is your artistic attitude? As I alluded to, my artistic attitude is that of a 50-something-year-old, pissed-off, American white guy. What is my approach to my work? I take the approach of an interpreter. I like to interpret, recreate relationships. One of the other things: What is your mission? It really depends upon what your mission is as an artist? Your mission may be to paint pretty pictures, and that’s a great mission. And then you figure out how you measure success against that. My mission is to be a storyteller. So I measure my success against that by how many stories I can tell that connect to people … When you making stuff, if your mission is to be a storyteller, you measure your success on how well people can engage with that story. In some cases they may just engage with it for entertainment. In some cases they may engage with it for intellectual stimulation. In some cases they may engage with it because of the material connection. There’s a lot of ways to approach that. That becomes a very individual question.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

I’ve been here for 10-plus years. I love it here. I think it’s incredibly beautiful year-round. That has creeped into who I am as a person, which inevitably creeps into who I am as an artist. I feel very connected to this place. I find that more and more my thoughts and ideas are wrapped into this sense of time and place. Any artist you talk to is making art to reflect the world around him. This is an important part of my world, so I spend a lot of time talking about it.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

Oh yeah. I know I would.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

No. However, my folks emphasized the arts. With my mom’s job, we were always going to art exhibitions and performances. When I was younger, I got to see Dizzy Gillespie play, Cab Calloway play, a couple of time. Storm King Arts Center is near where my family was from. Alexander Calder’s studio not too far away from where we lived in Connecticut. I was always exposed to the arts, but never really went into a professional artist’s studio until I met Michael Whelan. I was in my early 20s at that point. Now, my cousin got married in the old St. Patrick’s Church in New York City in the late 1960s. They had their reception in a friend’s loft, and we could see through the floor boards to the studio below.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

It has to be Noah. That man did so much to open my eyes, and really help me go from being lost in my work to someone who found themselves within their work. He was such an important influence. He still is. I can still hear his lessons. I still talk to him … He [also] had an influence on how I teach, and how I work with other artists, how I act as a person.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

That’s my wife’s job. We’re brutally honest with each other. We met in grad school in 1990, and been together since. We both have similar philosophical approaches to art. We were both mentored by Noah … We’ve worked together a lot, and we’ve worked apart a lot. We have level of language and communication when it comes to art that we both trust each other implicitly with feedback. We don’t always listen to each other,but the feedback is always strong and valuable.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

I could tell as many stories as I want to at home, and no one is going to hear them. You have to put the work out there. I have a mixed relationship with exhibiting. Painters’ studios are based on a 19th century model of a French painter: white walls, bright light, and the gallery is basically a white box meant to imitate a painter’s studio. My work’s not created in that way. I almost feel as though I’m taking it out of context that way. I love public art. I love when I can put art out in the public. The context is different. I’ve started doing more publications. And, I’ve actually got new twist on a photographic idea I’m working on. Even though “audience” is a theoretical idea, you have to get your work in front of viewers.

Why?

How do you know if you’re doing what your mission intends for you to do or not. With COVID, I’ve been focusing on the work, and have made an awful lot of work. In the exhibition world, everything has been pushed back. I didn’t have anything lined up before COVID started. I’m trying to stay out of the fray for a little bit, but I am starting to think about showing my work. That’s probably going to be my next project — look for a solo exhibition for my more recent work.

Let’s talk about your day job.

I’m instructor of visual arts at The Leelanau School. This is my 11th year teaching there. I teach film, photography, studio art, graphic design, and an experiential high school curriculum.

What is “experiential” curriculum?

At The Leelanau School we work with kids who are struggling with learning. We teach them how to learn, so our program is experiential. That opens us up to addressing different style so learning. If we can teach kids how to learn, they can learn anything. When you look at public standards curriculum, these standards are superficial, and designed to skip along the surface. They don’t address content. They don’t address practice. What we’re doing with our kids is trying to build their learning skills and process by going to a subject, and going deep, and really exploring it. It’s a very Foucaultian approach. You go into one pin point in history and then you explode that, and look at everything that was happening. So, if you want to look at the Ballet Russes for instance, you have to look at all the Modern Art that was happening in Europe. You have to look at what was happening in art history in Russia. You have to look at politics, and world conflict. One simple subject gives you an opportunity to go really deep and explore. That’s where learning starts to happen. Through that experience, we’re trying to create a scenario where the students can learn their learning skills so they can find their way through difficult subjects, for them; and then also building for the future. We are a college prep school, so our intent is to get kids ready for college. A lot of things I talked about with my practice really relates to this. My practice is very process-driven, and my teaching is the same way. My day job and my other job complement each other … [Kaz picks up his cell phone.] And again, these stupid things fight our process. We can’t tell the kids, “No, you can’t use your phone”; but they have to learn to use it properly. That experience becomes part of their learning. That’s a cool place to be. One of the reasons I feel so comfortable here is I’ve found a place where there is a strong sense of community, and we do a lot of our teaching through that sense of community. It’s not just about the academic classes. We are getting to build the whole kid, and that’s really cool. I’m able to be myself, which is incredibly valuable. Again, I chose my path not to make money, and to become wealthy. I’ve had a good life, and a lot of rich experiences, so I tend to measure my wealth in experience.

What challenges does teaching present to practicing your own work?

It’s always time. I’ve had good opportunities as an artist-in-residence. But that’s always the discussion — having the time and the resources to make art. That’s always the hard part for artist. And when you’re working a job, it’s eating into your time and your resources. If I were to go to a place where I had the time and resources, I probably wouldn’t be able to afford all the stuff I need to live my life the way I’m living it right now: the car, the tools, the cameras, the frames, all the art materials.

How is your studio practice supported by your employer?

At The Leelanau School, creativity is incredibly important to the entire community. Our community embraces the arts. They embrace me as an artist. They put up with me, with my crazy ideas both for myself and my students. They know if I get some harebrained idea, there’s enough trust there to know it’s going to turn into something cool for our students … I feel very supported. I can use the studios in the off times. There’s a great darkroom, and room to spread out … I really feel like I’m in a place where I’m not in a rut. If I were in a rut, teaching wise, it would be very hard … The hardest part of my life right now is my wife is in Florida, and I’m here. This is our eighth year of doing that. In our 25 years of marriage, we’ve been living in different cities more than we’ve lived together. Our goal right now as we’re getting on in years and starting to look at retirement is that we’ve both committed to being here. But when you have two art teachers with similar skill sets, looking for employment in the same place — like Leelanau or Grand Traverse counties where there’s not a lot of positions to begin with — it’s a hard scenario to work out. It would be wonderful to find a patron who could support us, and put us together. That’s why I play the lottery.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I’m a voracious learner. I love doing research and learning new things about old subjects. Really, my work reflects my own curiosity.

What drives your impulse to create?

Possibly, it might have something to do with my upbringing. I guess I always felt like I didn’t have a voice when I was younger. Everyone always told me what to do so I felt as though I was always pushed to the background. I found my voice through my creativity and feel like I can confidently tell stories about who I am and what I’m about.

Read more about Kaz McCue here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.