Creativity Q+A with Susan Tusa

Photographer Susan Tusa learned her craft in the days before digital, and plied it in the field of print journalism. She was a staff photographer with The Detroit News; and The Detroit Free Press, from which she retired in 2012 after 22 years. Susan is the recipient of numerous awards, and has exhibited her work in Michigan and France. During her decades as a news photographer, Susan created lyrical images that hinted at the kind of images she might create when not tasked with the work of reporting. She resides in Empire, Michigan.This interview took place in April 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

What draws you to the medium in which you work

That’s a difficult question at this point in my life. I’ve been photographing pretty much daily for 40 years. It’s just what I do.

Did you attend art school or receive any formal training in visual art?

My formal training was very limited. On a bit of a lark, I took a photojournalism course at Michigan State University and fell madly in love with the whole thing: the going out and shooting, and coming back and processing the film; then it magically appearing like a memory. I was at MSU thinking I was going try to become an environmental reporter. It hadn’t been a well-formed idea. I was just taking courses. And then I took a photojournalism course [in 1976-77], and completely changed directions. It hadn’t occurred to me that a person could make a living doing something they loved. I had purchased my first 35 mm camera a year earlier with money from unemployment checks [1]. I took a couple of courses per semester so I could work at the college newspaper [State News], and then doggedly pursued a career in photography. I started at small town weekly newspapers photographing things like little league tournaments and Farmer of the Week.

When so many people are working with digital cameras and technology, that darkroom magic is unknown or foreign to them. Is this a loss, the lack of direct experience in the darkroom?

Yes, I do think it’s a loss.

I think the more we know about, and the more we experience, in regard to any art we are practicing, widens our view. Having firsthand knowledge of different aspects of craft deepens the experience of not only practicing art, (in this case photography), but viewing it, and understanding it. I’ve met young photographers who have never even focused manually, and always use auto exposure, and I wonder how they can possibly get the results they want. The camera certainly doesn’t know, at least not yet. I think it’s really important to know the equipment you’re using and what it’s capable of. I also think that instant results cultivate unreal expectations, and an impatience that can be detrimental to producing good work.

I think there’s less time for contemplation, and that sense of what a photo actually is: a moment in time, a recent memory. The darkroom experience really illustrated that. You watched this moment from a while ago slowly appear. It’s a ghost, a mirage, and then it’s solid.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

Like I said, my formal training was limited. The photojournalism courses introduced me to the basics of black and white 35 mm photography – exposure, the function and relationship between shutter speed and F-stops, controlling depth of field, that sort of thing. I learned how to develop film, make black and white prints, and the importance of getting to know your subject. One of the first assignments I recall, was to come up with 10 portraits of people on the street – perfect strangers – and hand in not only quality prints of each person, but brief biographies. I discovered that I loved talking with strangers and finding out about the different lives they lived. And I was surprisingly comfortable doing it. (I’m not sure why, maybe from years of watching my mom talk with cashiers, plumbers, the guy on the phone, the mail carrier, pretty much anyone she came in contact with.)

The rest of my education was trial and error. Lots of error. I remember while working at The [MSU] State News, my boss, a prickly sort, sent me to shoot an advertisement at a women’s clothing store. He loaded me up with a closet full of equipment I had never touched — lights and batteries, umbrellas and light stands — and sent me off to shoot the ad. He was a bit terrifying. So, rather than speak up and admit that I hadn’t a clue how to use any of the equipment, I muddled through with predictably terrible results, and got fired. It took a while, but after a lot of experimentation and wasted film, I learned to manage lights quite well. After I was quite comfortable with them, I found myself avoiding them whenever possible anyway, even when shooting food or fashion. I always prefer shooting on location or using window light and reflectors. Too much equipment always feels like a barrier to me, and I never thought that the artificial light I created was as pleasing or effective as the light of the world.

Describe your studio/workspace.

I practice photography everywhere: inside my home, outside, wherever I am or wherever I am assigned to go. Most often, these days, it’s wandering the trails and shore of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

My editing/printing space is in the bedroom/office/laundry room in the little house I just moved into. It’s tight, but it works – a perk of not needing a darkroom anymore. Years ago, pre-employment, I made prints in my bathtub. My enlarger was on small back porch that I blackened with dark plastic bags, towels and lots of duct tape. Now I do all my “developing” on the computer. I’m quite comfortable doing what I used to do in the darkroom, in Photoshop, and since I left the Detroit Free Press. I’m learning to feel free to make more adjustments than I was ever comfortable with. When working as a photojournalist, it’s not acceptable or ethical to alter photos in any way. Basic toning — that’s it. If I photographed someone and didn’t notice the bushy tree in back of them looking like an eccentric’s hat because of the angle I chose, well, too bad. We don’t alter reality. I get so angry at people crying “fake news” when I’m well aware of how the vast majority of journalists and photographers work so hard to produce an accurate representation of whatever the subject, story, or situation is. Even now, when I’m doing a close up of something in the woods, I feel a twinge of guilt if I remove a twig from the scene; but I’m getting over that little by little as I work on artwork. I’m becoming a bit more playful, because I can be.

You have been in the process of transitioning from your professional work as photojournalist with the Detroit Free Press to the work of a studio artist.

I left the Detroit Free Press at the end of 2012. I don’t consider myself a studio artist. I approach my work in much the same way I always have.

How are the two forms of photography alike or different?

I don’t think there is a big difference between the work I did at the Detroit Free Press, and the work I’m doing now except the content and pace. I rarely have deadlines, don’t have daily assignments, and live in a different place. I’m still photographing most days, and when I’m not, I’m editing, printing and trying to figure out ways to make this daily practice of mine useful. I’m trying to sell my artwork, which is relatively new to me. I’m fumbling my way around the art world, figuring out pricing, limited editions, that sort of thing.

Which of your photojournalist’s tools/equipment have transferred to your studio work?

My tools are pretty much the same, except that I don’t have as many cameras and lenses. The paper used to provide whatever we wanted in terms of equipment, and now I have to buy my own, so I can’t afford the really long lenses I’d like; or to replace my older cameras with the newest, better, faster versions.

What did you bring [visually, philosophically, aesthetically] from your former profession into your studio work?

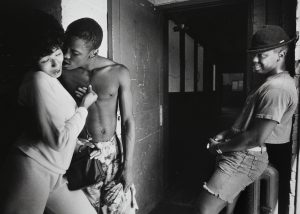

My visual, philosophical, and aesthetic approaches to my work have developed throughout my career. And they continue to develop and change as I do. As a photojournalist I’ve had to photograph everything – portraits, prison riots, fires and fashion, the rich and famous, the poor and impoverished, violence, kindness, mayhem, quietude. The challenge was always to get to the truth or essence of whatever it was I was shooting, make it visually interesting/artful in terms of composition and content, and fulfill the needs of the paper – the space it was destined for. The difference now, is that I’m most often photographing with no assignments, deadlines, or the demands of a particular publication.

But I always have a camera, and inevitably something will catch my eye: a shift in the light, a sound, some movement on the ground or something incredible at my feet that I’ve never seen before. Whatever it is summons me to stop and look more closely. I’ll begin shooting, and then I’m pretty much lost to whatever drew me in. I’ve always loved being in nature, where life and death and the whole mysterious mess becomes less scary. The “I” is replaced by a kind of mindfulness.

Please elaborate.

When I begin photographing something, and “working” it, nothing else exists. I’m not thinking, just seeing and making adjustments in focus, depth of field, shutter speed, changing my position — standing, kneeling, laying down, watching the scene or whatever it is change in the viewfinder, shooting frame after frame. I’m not thinking about the past, or worrying about the pandemic or politics, mass extinctions, what I’m going to make for dinner, or the million other things that are always scrolling through our minds. All I’m doing is seeing.

In the Washington Post article about the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, which your photographs illustrated, Rebecca Powers said you “often recite poetry while hiking.”

I don’t have a lot of poems committed to memory, but sometimes I’ll think of a part of a poem and look it up. I like trying to memorize poetry while hiking. I find it easier when I’m out walking to memorize things. Sometimes walking, a poem will occur to me, and I’ll incorporate it in the pace of my steps. A few poems I know by heart are like prayers, particularly a couple by Mary Oliver. She’s so in tune with nature. It’s a nice way of centering.

Thinking about poems doesn’t take away your focus from your walk, and the seeing part of your walk.

It’s almost like the walk and the seeing conjures up the poem. I never memorized a lot of poems throughout my life; but now, it’s probably a good idea. My legs are moving. I want to get the brain to do a little work, too.

I used the verb “illustrated” to refer to your images in the Washington Post article; but I don’t think that’s accurate. Your images stand on their own as much as Powers’s words stand on their own.

The words and photos aren’t supposed to mirror each other. Ideally they work together to communicate and make a connection with readers/viewers.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Life, death, the all of it, I suppose.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

I’m not a pre-planner. I might return to something I’ve seen when the light is better, which for me usually means softer or darker. Even when I do still life photography, there is no real plan. I begin with something I might’ve picked up — a rock or dead bug — and go from there.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

I always have several things going at once; but I’m very unorganized and photograph an unmanageable volume of work. I have hundreds of thousands of files and negatives in boxes and folders, on hard drives and my computer desktops that need editing. During the summer months, when the light is harsh, and the heat and chaos are a bit much for me, I spend time inside editing and trying to create some order out of the chaos. I have an embarrassing number of folders on my desktop computer, and lately I’ve been doing nothing with them except adding more images. Each of these folders represents a potential series or project; but at this point they are becoming less defined and more unwieldy.

What’s your favorite tool?

Whatever I happen to be using or have with me on my walk. My Canon 5D Mark II with various lenses is what I like to shoot with most; but it’s also heavy and weighs me down [2] when I’m walking a few miles at a time. Sometimes I’ll carry a point and shoot, and always my iPhone. If I leave the Canon behind, I can be sure I’ll come across something particularly beguiling and I’ll regret it, so I try to have my camera and at least one lens with me. I purchased one of the new iPhones, simply for the camera. I justified the purchase while dealing with a shoulder issue not too long ago. The capabilities of that camera are astounding; but I also have to be careful not to submit to the convenience, because the days that I do, are inevitably the days when I’ll kick myself for not carrying the heavy stuff.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I always carry a notebook and write down random thoughts that might occur to me, or that I might want to expand on. A couple of years ago I completed a master’s degree in creative writing [3], and am in the process of trying to combine the two arts. It’s really a difficult and interesting process. I’m still a novice in terms of writing. My writing is about as organized as my images. Folders, both physical and virtual, notebooks, scraps of papers, piles of them all over the place.

How do you come up with a title?

I’m terrible at titles. Generally, I try to keep them simple: a geographical location, a botanical I.D., or “untitled” if I can’t think of anything. My daughter cured me of trying to come up with meaningful names when I was getting my first exhibit together. We laughed pretty heartily at how lame the names I was coming up with were. She is my go-to editor. Never afraid to tell me the truth or hold back an opinion, and I trust her eye and judgement.

What’s the job of a title?

I’ve learned, that for me, a title is simply a point of reference. Like a number. If the image is particularly abstract, perhaps a word or two as a way to orient the viewer. I don’t like titles that qualify the subject in anyway or tries to induce a reaction in the viewer. I never use a title to spell out a particular emotion or whatever it is that I’m trying to communicate. I think it’s somewhat disrespectful to the viewer. If what I was trying to communicate isn’t within the photo, the image failed.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

When I took my first photography course.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I’m active on Instagram and follow visual artists from all over the world. Looking at images every day is inspiring. Paintings, photos, sculpture, all of it. Every encounter we have with art affects us, I think, and influences the slight shifts in direction our own art takes. Whether that encounter or immersion is via social media, an art gallery, in books or films, it all becomes a part of us.

What’s its influence on how you let the world know about the work you make?

I think it’s a way of getting work out there. As your community grows, so does exposure. I’ve gotten some freelance work that way, sold some art, and was asked to participate in an exhibit through Instagram.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

To make art.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

I believe that everything is connected to everything else, our memories and histories, all of it affects who we are and our world view. I guess every part of the world I’ve had the privilege to be exposed to – physically, virtually, intellectually. All of it has somehow found its way into my work. I could look at one of my recent photos and say, for example, this photo is because as a child I went to a Catholic girl’s school or because I recently read a novel by Chris Abani, or because I took a walk and saw that dead mouse, all of it’s in there somewhere isn’t it?

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

Nature is pretty much center stage here, and since I moved to Empire full time a couple of years ago, it has taken center stage in my work too.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place?

I think my work is definitely a reflection of wherever I am, both physically and mentally.

If not directly reflected or depicted in your work, are there other [unseen] ways Northern Michigan informs your work?

I’ve spent the majority of my life in Michigan, so my work most likely carries the sense of Michigan.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan? Would your work have a different look or appearance?

There would be different content, of course, but I’m sure there would be similarities in the mood or texture of the photos. I lean toward the quiet, and solitary, sometimes dark, whether in color or black and white. My color photos are most often monochromatic. That said, if I lived in Cuba, say, I’m pretty sure I’d be photographing the rich color palette there.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

Just an uncle who I rarely saw.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

When I was younger, I read a biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, and was awed by her vision and the way she lived her life. That might have been one of the sparks that first pointed me in the direction of visual art. I didn’t grow up in an artistic household. I took piano lessons in the first grade; but a cranky teacher convinced my parents that I was not musician material (and this was after having just mastered “Yankee Doodle”). I have no memory of trips to art museums, art lessons, things like that.

It’s difficult for me to name one person. I’ve had the privilege of working alongside some of the most talented photographers and editors out there – Eli Reed, Stephanie Sinclair, Taro Yamasaki [4], Joel Meyerowitz, Joyce Tenneson, Romain Blanquart, Kathy Kieliszewski, David Gilkey — at the papers I’ve worked at, on various assignments, and during different workshops. Some are well known, some are not. But their collective knowledge and different ways of seeing widened my vision and continues to do so.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My daughter. She’s not afraid to say exactly what she thinks, she’s smart and funny and has an incredible eye.

You’ve moved from having a reliable, regular platform for your “showing” work — i.e. The Detroit Free Press — to a place where you are asking people IF they’d like to show your work.

Entering exhibitions — I didn’t even realize that that was a thing. The first exhibition I was a part of, I was contacted by a man who was curating exhibitions at the Detroit Artists Market. I just thought gallerists found you. I’m starting to learn the process.

Exhibitions are prohibitively expensive in terms of getting the framing done. I’m particular and don’t make frames myself. And then you have to figure out prices. I have a friend who’s been doing this for a while, so she’s been advising me on the business end of things. It’s probably a good thing I had a regular job because I’m really bad at it. I’m trying to get better because I’d like to get my work out there and sell it.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

I’ve only been involved in a handful of exhibits. I suppose their role is to release the work into the world, and hope it speaks to someone. Exhibits also provide deadlines which for someone like me who has spent most of her shooting life with daily deadlines, is really helpful. An upcoming exhibit is a sure way to get moving on some of the series in those bulging folders I mentioned earlier.

Footnotes

1.) Susan had found employment as an EKG technician, proofreader, cashier at a bookstore, and waitress.

2.) Susan estimates “heavy” at 20 – 25 pounds.

3.) Susan received a BS in cultural anthropology from Grand Valley State in 1975; and an MFA in creative writing from Pacific University in Oregon, fiction, 2018

4.) Taro Yamasaki, a Pulitzer Prize winner, resides in Leelanau County.

Susan Tusa is represented by the Sleeping Bear Gallery in Empire. Learn more about Susan here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Thanks to Susan Tusa for generous use of images.