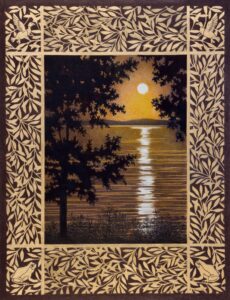

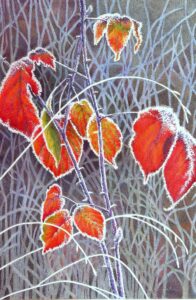

Leelanau County artist Margo Burian, 61, has carved a niche for herself in the cultural landscape. Her atmospheric paintings of the the locality’s land, sky, water, and historic farmsteads are known and coveted by a wide range of fans and collectors. She began her professional life as a commercial illustrator, and has traveled from depicting Sponge Bob to painting the ephemeral place called liminal space. “I knew I wanted to be an artist since I was five,” she said. In the years that followed, Margo has honed and built on that desire, and sharpened her ability to talk plainly, albeit deeply, about the complexities of her calling.

This interview was conducted in August 2023 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Margo Burian

Describe the medium in which you work.

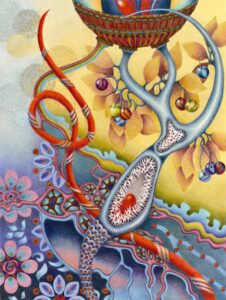

I work in a couple different mediums. Mostly, my medium of choice for making paintings is oil paint. I also do acrylic paintings, but not with a lot of regularity. My side gig to the oil painting is painted paper collage and mixed media.

How is collage worked into your paintings?

The collage I tend to keep separate from the oil painting. The two don’t go together in a way that makes sense. I will use bits of painted paper as a way to make adjustments to oil paintings. It’s like an un-do edit. If there’s a painting I’m struggling with, and I’m trying to figure out if it’s a particular color or shape, I may cut a piece of collage paper to place it over the painting to see if that’s what makes the difference. Generally, I see collage as a separate entity.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

I received a BFA from Kendall College of Art and Design [1992] with a major in Illustration. I was a commercial illustrator for about 20 years [1990 – 2010] before I came to painting. I had a lot of good accounts: Meijer, Scholastic, I was licensed to draw Sponge Bob, and Hollie Hobbie and Dora-the-Explorer through Nickelodeon, a lot of work for American Greetings. When I started painting, I realized I didn’t have enough knowledge. Rather than go to graduate school, I thought I’d do a self-styled MFA, choosing to study with artists who resonated with me, and whose work I appreciated. That led to doing a series of workshops with a mentor, Stuart Shils, and Ken Kewley. I find that taking workshops is a better way for me to get knowledge I don’t have rather than committing to going back to college.

How do workshops address, and advance your need?

I’ve always been someone who’s interested in education. I’ve always been a seeker. The cup is never full; but I keep aspiring to fill the cup up with more knowledge. I really enjoy being in a learning environment with other creative professionals. I like to share ideas, to have exposure to people and ideas I might not otherwise have if I was holed up alone in my studio.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

Especially with having a degree in illustration, I become proficient in a number of media. I started as a watercolorist, then did pastels. Didn’t do a lot of oil painting in college because I couldn’t afford the paint and the canvases; but having that illustration background was helpful. It solidified my drawing skills, and because I knew from the get-go I wanted to freelance, it helped me foster a sense of being dependable, and developing good studio work habits. When you work for yourself, there’s no one to pick up for you. You have to learn time management. If you don’t learn time management, you either lose your clients or work all the time. I ended up working all the time, which led to me switching to painting. I was working too many nights, weekends, holidays, birthdays, and finding that I wasn’t enjoying the commercial work-for-hire

Describe your studio/work space.

I’m fortunate in the fact I have two studios right now. The studio I have downstate is a bright, well-lighted third stall garage that was converted into finished space. When we built the home in Grand Rapids, we knew I was going to need working space — I’d just moved out of a 1,000 square foot warehouse into a 240-foot garage space. That was a challenge, but the lighting and the fact that space is directly connected to our home is fabulous. When I have the ability to work on premises, i.e. at my own home, I’m more productive. There’s no drive time. I’m someone who wanted to work at 9 o’clock at night, it’s doubtful that I would drive to my rented space [Margo has a second studio space in Leelanau County, where she and her husband have a second home]. When we’re in Grand Rapids, having access to the studio, if I only have an hour, I can spend that hour prepping things, or gluing paper to board, or organizing, or cleaning brushes. I’m less likely to work for an hour if I have to drive somewhere to do it. Having the studio space on site is almost a necessity for me.

Describe the Leelanau County studio you rent?

That is very small. Probably the size of a bedroom, which presents its own challenges. I’m not someone who likes to look at my work all the time, so I don’t have a place to turn the work away there. Being right in the middle of town, especially in mid-summer, can be a challenge as well. I very often have a note on my door asking not to be disturbed. I find that people are interested, but when I only have a short block of time to work, it’s hard having someone knock on your door just to chat. I love interacting with people, but it’s not good for work. I am easily distracted.

Talk about some of the themes and ideas that are the focus of your work?

A big theme for me is connection and intimacy. I tend to make a lot of small work, which is a hangover from my illustration days. If you’re working on tight deadlines, you’re not working 4ft x 4ft. You’re working 12 inches x 12 inches. Or sometimes even less. I’ve always been drawn to small work. It forces the viewer to come closer to look at it, which creates intimacy. As a painter of landscape, it’s about connection to the land, to the people. We’re fortunate to live in an area that is remarkably beautiful. People feel connected — whether they’re local or visiting. There’s an appreciation for the beauty of the area, its people, and the wildlife. For me, that’s the basis of my work.

You’re also known for your paintings of old dock pilings sticking up above the surface of the lake. You’ve done your fair share of depicting some of the historic agricultural structures. Your work allows for human artifact to enter the equation.

When I started painting, I focused on the land exclusively. I’m finding that I’m really interested in how we, as humans, have interjected ourselves into the landscape, and what we’ve done. I’m not saying it’s 100 percent all good; but there is something about the way, especially in this area, that structures interface with the land. In a way, it’s timeless. Especially with the park [Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore], and all the preservation that’s been done with all these old farmsteads, we’re in a liminal space: They’re not really of our time, but they’re holding space between the past and the present. I find that interesting. We’re never in the future, we’re only in the present moment, and we’re never in the past either. So, the space of the present moment is what I’m trying to capture with some of those structure paintings.

One of the things I wonder about is, for people who focused on the landscape — thematically — there is the relentless march of civilization that impacts, and destroys, and has its influence on the landscape. What do you think about that?

It’s tough. I’ve been a Northern Michigan girl practically my whole life in one way or another. I remember Traverse City and Glen Arbor from the lens of 40, 50 years ago. I understand progress can’t be stopped; but I wish it could be more thoughtful. I’m afraid, more people discover the area, that we lose what makes Northern Michigan special. I don’t have an answer. We shouldn’t close the gate; but we need to be very intentional about the way we move through the land, and the way things are developed. We need to have, as a culture, a major shift in our thinking about the land and its resources.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

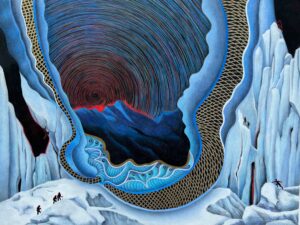

My work is based in observation. I’m always looking. Throughout the course of the day, I’m looking at light, and shape, looking at my environment. Generally, an idea starts with a flicker of an image. I might be driving somewhere and see how the light is catching. If I don’t have time to stop, I file it in my memory bank, and try to remember to go back and check the same spot to see if it really holds my interest. If it does, I’ll go on site and make some drawings, make some acrylic paintings in my sketch book. I’m not much of a plein air painter. I like my studio. I like to be quick and mobile enough to catch the base information I want. Then I start to develop the work from there. Oftentimes, I like to work small and then scale up. The reason for working small is to see if my first instinct is correct: Is this a painting that has good composition? Is it going to be a painting that has interest for me as a painter? Are there things I can do to strengthen the original drawing; or add something from memory to it. The reason for working small, especially from the beginning, is to build a library of information. As I start to scale up, I’ve got some of the bigger problems figured out. Scaling up comes with its own problems. The tools are different: they’re larger, they react differently, the movement of the arm is different, the stepping back is different. It’s almost like a completely different painting once you begin to scale up.

Let me go back to the conversation about connection and intimacy, and the relationship to small work. You do also paint large. So: What’s “large”? And, how does connection and intimacy continue when you scale up?

For me, “large” is 24” x 30”. I also scale up to 40” x 40”, 40” x 50”. It does change the intimacy. You have this significantly larger thing, which has more presence because of its size. But just because something is big doesn’t mean it’s better. One of my big frustrations is people tend to write off small paintings in search of the holy grail. The work I make is the work I make, and I feel that if someone needs a really big piece, I may not be the person for that. The work I make tends to be smaller in nature. For years, I struggled with that. I’ve decided it’s the work I make, and I’m just going to stand behind it.

Do you work in a series?

I do. It’s a little bit of an ADHD [adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder] series because I tend to jump around sometimes. Thematically, I can leave a series for a long time and come back to it, but the danger in that is that I feel like my work is always evolving. I don’t feel like I’m the same painter I was two years, as I was four years ago, as I was five years ago. I try to avoid getting caught in the trap of stylization. I’m looking to have the work be a direct interpretation of my own emotional state as an artist. I continually take classes and workshops because I don’t want to just make paintings that look the same. If I were working in a series, and completed five paintings right in a row, the danger is they would have all have a similar working method. If I spread it out over a few years, one could look very different than the other but still thematically related.

What’s your favorite tool?

Right now I am super into playing cards that I can cut up into small shapes to manipulate the paint. You can use them to smear. You can use them to push paint around. You can cut tiny shapes out if you need to hit the right highlight, you can also use them as a great straight edge. Just a cheap pack of Bicycle playing cards.

How’d you discover the tool side of playing cards?

I was looking at the work of a friend, Carolyn Fehsenfeld, who’s a brilliant painter. She had just released this whole set of paintings that had been done on playing cards. I’d been working with cold wax and decided I wanted to do a painting-a-day as a warm-up exercise before the studio. In the month of March, I made 31 paintings on playing cards. There was a day when I needed to make a small adjustment to the painting. I needed to slide the paint around, and cardboard — which I also love using — was too thick, mat board was too thick. So, I thought, “What about this playing card?” I just started hacking little pieces off of it, and started moving the paint with the painting card.

Do you use a sketchbook, or a work journal, or some sort of bound thing to record your thoughts and notes as you’re working?

I’ve always worked in a sketch book, and I probably have at least 30 sketchbooks in my studio downstate, from when I was in college all the way up to now. The sketchbook has always been a big part of my process — especially when I discovered I wasn’t much of a plein air painter. The plein air movement is great. It gets people out. You start looking at color, composition; you learn to make quick choices. There’s a lot to be learned from painting from [direct] observation. I use the sketchbook as an information-gathering tool. A lot of times when I’m out, I’ll make drawings in the sketchbook to build a visual reference for myself. It’s almost like a crutch, but I’ll take some photos, but I don’t work a ton from photos. I use photos as a back-up in case I don’t get enough information. Especially in the way I paint, it’s not all about the details. I probably don’t even need the photo, but psychologically I do.

Talk about the role social media plays in your practice.

Oh, cringing. It’s so hard for me. I feel reticent about posting work, and I shouldn’t be, but there’s something that I don’t like about [the pressure] to be continually posting. It’s a way to let people know what you’re working on. A good way to stay connected with people. But I also think it’s so easy to look at hundreds, if not thousands, of images in a single day that we haven’t properly learned how to look at paintings. You can’t really tell what an image looks like on Facebook or Instagram. You don’t get the surface presence. It’s flattened. It’s like there’s another filter between you and the art. I don’t think you can feel the piece as well. When you’re looking at that much art, every day, on social media … I know, for me, it makes me start to second guess what I’m doing, and I don’t want to be in a position of second guessing what I’m doing. I don’t want a lot of influence [into her creative life] that might not necessarily be helpful. The first time I ever saw a Monet painting was most likely in an art history book, or one of the art books my grandmother had given me for a birthday. The first time I stood in front of a Monet painting, I bawled my eyes out. I walked into MOMA, and turned the corner, and there was Monet’s water lilies. The rush I got from that painting was incredible. Opening a textbook — or, in this day and age, opening a screen — you can’t have that same experience. You miss a lot of context with social media. You miss the human experience. You miss the connection.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

To surprise us. To enlighten us. You show us another way of seeing things, and another way of being. It’s not that life is just about acquisition of things. It’s about experiences.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

No. I didn’t. It wasn’t until I took this community ed life drawing class at the college in Petoskey — which was taught by Doug Melvin. I knew, since I was five years old, that I was an artist; but I never realized that I could have a career in the arts. He was the one who said, “What are you doing waiting tables?” I don’t know. I’m having fun, living in a resort town, working at ski resorts [at age 25]. When I was in high school in Saginaw, career counseling was all about going to work in the [auto] plants. The high school I was attending, they weren’t doing a lot of college prep — maybe for the kids who had math and science aptitude, but I was the art kid. There wasn’t a lot of guidance there. Doug Melvin said I should be going to college, and he said the words, “I’ll help you.” So, it ended up with me being able to get a scholarship, and changed my life as a result of my experience with Doug Melvin.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

First and foremost, Stuart Shils. I met him in 2009. He’s an internationally known painter from Philadelphia, and remarkable educator. He was my mentor for about 4 years. He opened my eyes to what painting could be, and for that, I am forever grateful. He was also instrumental in facilitating a teaching assistantship — with him — at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in 2014, as well as referring me to a month-long residency at the Heliker-Lahotan Foundation in Maine. I learned so much from him; but at some time, you have to leave your mentor. You start hearing, especially when you’re mentoring under someone who is as powerful a painter as Stuart, someone else’s voice in your head over your own. Then you have to really look at the role of the teacher-student relationship. For me that meant standing on my own ground. We keep in loose contact, and I can never thank him enough for all his insight.

I’ve also had the good fortune to study multiple times with Ken Kewley. Ken is another East Coast painter, who also teaches and works primarily in acrylic paint and collage. I’ve learned so much from him about color, shape, and letting go of preconceived ideas.

Where or to whom do you go when you want honest feedback?

I have a group of friends here, and they’re generally my first calls. We’ve all worked together as creative practitioners, and we’ve also worked together collaboratively on art projects. I trust their judgement. I know when we talk about the work, it’s done with genuine care. They can be critical; but within the criticism there is a caring. We all want to see each other succeed.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

It used to have a bigger role. I don’t enter a lot of juried shows anymore. I’ve gotten out of the habit. I often don’t make time to be sure the work can get back and forth [from studio to exhibition site]. I’ve been very fortunate to have successful sales exhibitions, so lots of times I don’t always have a lot of work in the studio I want to send out.

In the beginning of your career, when it was more important, what role did exhibition play then?

It was about validation. I’m my own worst critic of my work. This is a problem when you have a small studio. I don’t have any place to turn it away or store it. It’s fun to come into the studio when I haven’t seen a piece for a while, and be surprised by it. Initially, it was about validation that I was really moving in the direction I wanted to be moving. Now, I don’t feel I need as much external validation as I did. When people come into my studio, they come in and want to make comments about pieces I’m working on, and I ask them not to make comments. Generally, my rule is if it’s in a frame, you can say anything you want about it; but if it’s not in a frame, I ask people to refrain, at least when I’m in earshot.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I know I can go through stages where I’m painting a lot, and then I pull back from it, and then I switch to something else. It might be cooking. It is very often knitting. And those things, when I step away from painting, all recharge my battery. I’m kind of an introvert. I like a lot of quiet. I like a lot of down time. Also, getting together with friends who are painting — going to an art camp or to a workshop. If I’m stuck or struggling with an idea, I find that being with other people who are creative, who are actively engaged in their own practice, being around those people helps me to extend my own creativity. I don’t really need to go to workshops; but I need to go to workshops to have the experiences of being open to new ideas, new materials, and to recharge. I consider myself a life-long learner.

There’s really no end point to learning, is there?

There shouldn’t be. That’s what keeps us young, our brains and our ideas fresh, to always be learning, to always be seeking, to open to surprise. Some of the surprises are better than others.

It’s another one of those process versus product things.

In the switch over from illustration to painting, that was a really hard thing for me. As a commercial illustrator/graphic designer, you were dealing in product. At the end of the day, your client doesn’t care how you get there if you’re delivering something that meets their expectations. There’s no talk about process. It’s always product. In your mind you know you’re always creating a product. That switchover was difficult for me at first, and sometimes even carries over now. I don’t want painting for me to be only a product. I think, when I get into trouble with painting, is when I see it as I have to have X amount of sales — because then, I takes the surprise and the fun out of it. The work I get the most satisfaction from is when I’m experimenting, when I’m learning something, or I’m working with new imagery. I’m kind of a materials weirdo. I like to try a lot of new materials and processes. That helps keep that product issue at bay: I can’t make a product if I don’t know what I’m doing, and I always feel like I don’t know what I’m doing. I remember my mentor saying that to me: The best place to work from is a place where you don’t feel like you know what you’re doing. I understand that now. It’s not always comfortable; but at the end of the day, I’m generally more satisfied with the work.

What drives your impulse to make?

I’ve always been a maker, and I’m not exaggerating when I said I knew I wanted to be an artist since I was five. I started knitting when I was 10. I had my first, real museum art experience between the age of 8 and 10 at the — my grandma enrolled me in classes there. She took me over to the Singer store to learn how to sew when I was 13. I don’t know where that drive comes from except that I’ve always had it, and I only feel most connection with myself when I’m making and creating. It’s so deeply embedded in me that I have to be making.

Learn more about Margo Burian here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.