Creativity Q+A with Judith Shepelak

Judith Shepelak’s road toward a full-time studio practice came after she’d worked as a paralegal, then a graphic designer, then a landscape designer. In between she raised her children. For the last two decades, her creative focus has been on ideas and subjects that interest her instead of a client; and she executes them all in colored pencil — a labor- and time-intensive medium. “[Creating a drawing with] colored pencil is a very long process,” said Judith, 74. “What I can do in a pastel [painting] in five hours is probably going got take me about 40 hours in colored pencil.”

This interview was conducted in October 2023 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured [left]: Judith Shepelak

Describe the medium in which you work.

I work most of the time in colored pencil. But I also do pastel work.

What do people need to know about colored pencil to better appreciate work done with it?

[Creating a drawing with] colored pencil is a very long process. What I can do in a pastel [painting] in five hours is probably going got take me about 40 hours in colored pencil. A colored pencil drawing begins by laying down light base layers, then you add and add and add, changing your colors. [The process] can add up to about 15 layers. So, I do my piece about 15 times in order to get the colors I want.Is there a blending process that takes place with all this additive color?

Colors will blend themselves because of the way the pencil lead is made. But there are also about seven or eight blending tools. A lot of us use gamsol [an odorless mineral spirit used to thin paint] ] — because it dissolves some of the pigment, and you can move it around.

How did you start using colored pencil?

I was a landscape designer for a period. I would do the landscape drawings, and color them in with colored pencil. I didn’t think a lot about it until one day, I went to somebody’s house, and they showed me that they’d framed my drawing; and I thought maybe I could just do colored pencil drawings. I didn’t have any training in colored pencil. That’s when I started to take workshops. At some point I thought I would do botanical art because I was taking some of my workshops at the Morton Arboretum in Chicago. But then, that was so limited. I was using a magnifying glass — I felt like it was a job, and I just wanted to be free with my art, so I sought out other workshops.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

I started out at the American Academy of Art in Chicago. I decided it was costing me as much to go there — I was still living with my parents — so I decided to go to Northern Illinois University in graphic design because I also decided I needed a job after I got out of college. I finished off with a BFA in Graphic Design [1972], but I had other art courses — woodcut [printing], weaving.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I’m not sure that my formal training in graphic design helped [me with] what I was going to do later in life. I did have one instructor [Nelson Stevens who taught woodcut printing at Northern Illinois University] who was extremely helpful, who taught me how to think beyond the box. He would sit down and draw with me. He’d add a couple of lines and then say to me, Now I want you to add to this. We’d go back and forth, and I learned this freedom of in drawing — I didn’t have to always draw exactly what I saw. He was just trying to free me up. Graphic design is different from fine art. It’s a job of putting together a visual piece, but you’re not using a tremendous amount of creativity. Everything you do in graphic design is dictated by your client.

Talk your studio space.

When we moved into [a townhouse in suburban Chicago], I fixed up the closet so I’d have all kinds of space to store all my art supplies, and long flat files for paintings. The rest of the studio space: I have a table that I work on, and an easel. I have all sorts of flat workspace where I can lay work out if I’m framing it. And, I have my own desk area where I keep my computer.

The one I have here [in Traverse City/Northern Michigan] is a regular bedroom that’s probably 12 feet x 16 feet. I have my drawing table, and I have areas to put all my tools that I’m working with, but it’s not as elaborate. Anything I need to store, I [store in] a little side room. It’s not the best, but it’s fine. I have the [Grand Traverse] Bay to look out on.

How does your studio space facilitate your work?

Here, in Michigan, I have floor-to-ceiling windows on both sides of the room, so I get to look out on the forest, I get to look out at the Bay. I have plenty of light here. I never feel like I’m missing anything when I come here to work. In Chicago, it’s another story. [The studio is] in a town home. And, I don’t have the same visuals, but I have the space. Anytime I want to do framing, that kind of work, I leave it for Chicago. If I want to work on my website, [maintaining] my files and portfolio [that also takes place in Chicago]. Here [in Northern Michigan] I just work a lot.

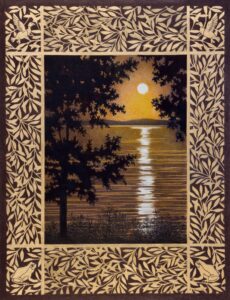

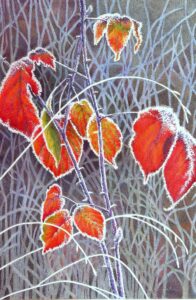

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

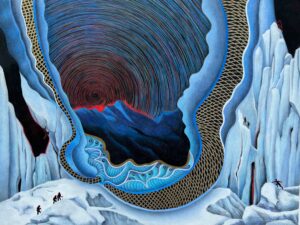

I spend a lot of time on landscapes, on abstracts, and I have done botanical work, but I don’t find that exciting. Lately, I’ve been delving into working with people — not portraiture. There’s a lot to learn, in colored pencil, when you start in a new area. Portraiture [requires] a whole different set of colors than you’re working with in landscaping.

What prompted the introduction of figures into your work?

Most of the work I do comes from photographs I’ve taken. The first time I put a human in, it was in a landscape where my husband and I were hiking, and I had a picture of him in front of me. I started adding people to the landscapes by showing them hiking. And then, I had grand kids. There were so many cute photos that I’d get from my daughter-in-law. I did one during COVID when they were all at their doctor’s office getting shots, and they all had their masks on. I had a watercolor instructor in school who said that once he started putting people into his landscapes, they were more interesting. There was more of a story. So, then I tried that. And I do think it does make a difference. People are very interested when they see a person in the painting because then they can see themselves in the painting.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

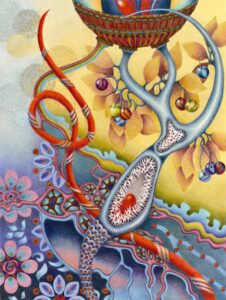

Almost anything in my life can be a prompt. I could read a line in a book, and my mind just zooms off into a visual. Or I could see somebody else’s art and think that that’s [an idea for] a picture. And I’m somewhat political. I have several pieces that reflect on what’s happening currently in the world. A lot of those end up as abstracts. They’re more creative.

Why does the political work get abstracted?

Sometimes I’m not expressing a particular event. A lot of times it’s an emotion. I’m expressing how I feel inside about what’s happening. It always comes out in an abstract form. I really can’t draw political characters. That doesn’t interest me. I’m doing this for myself. It’s a way to relieve tension by drawing.

What’s your favorite tool?

The eraser. You can erase half of a piece of art — colored pencil is a pencil medium. There’ll still be a stain in the erased area, but you can rework it. I have all types of erasers, and so do other colored pencil artists. We talk a lot about how we remove things.

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

I’ve always done work by hand. When I started out in graphic design, everything was done by hand. There were no illustrations you could buy off the internet. If you had to lay down type, you had to glue it up and lay it down by hand. I am a person who likes to construct. Even as a kid, I’d construct things out of popsicle sticks. I love to bake. I garden a lot. I use my hands more than I use my mind — not that I don’t use it. Everybody, in some way, creates with their hands — whether you’re building a home or painting, you’re always using your hands.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life?

There’s a certain reward to doing things with your hands. You’re putting yourself into that piece. And that’s a good feeling. It’s a different feeling than when you read, or write a book. There’s a different feeling there. Some people, including myself, do better when we’re creating with our hands.

When did you commit to working with serious, professional intent?

I worked for about 10 years after college. I worked as a paralegal, then I became a graphic designer. When I had my first child, I still worked freelance in graphic design, and then I was a full-time mom. I spent a lot of time donating time to a lot of organization, but I wasn’t doing anything for myself. When my kids got older, I went back to school for landscape design, and ran my own landscape design business for about 10 years. That’s when I started drawing. Once my kids started going off to college I started drawing more. And the more I drew — suddenly I had 20-25 pieces — I thought, What am I going to do with all these things? I started looking for galleries where I might show [around age 55]. I started out showing work in a framing gallery. Then, I started looking for real galleries. I’m still looking for galleries. When I look back, sometimes I regret that I didn’t start earlier

What role does social media play in your practice?

Having come to Facebook and Instagram late in life — I do have a website — I find I don’t like to spend time doing that. Probably because I don’t have the same versatility that my children do. They seem to understand what everything means, and where to find certain things. [NOTE: Judith adds: When I was referring to my website, I meant that I didn’t like updating it, mostly because half the time it’s a slow process to figure out how to technically achieve what I am trying to do and ultimately it becomes frustrating. My children are better at understanding how to get from point one to the next.

And with Facebook and Instagram, I find them a waste of valuable time. They do serve a purpose for me occasionally, but in my life, if I want to find out how you are or where you’ve been I’ll call you to catch up (which I do, and enjoy the conversations immensely). If I want to know about politics, I’ll watch the news, and for my other interests I go to books and magazines. There is nothing more relaxing than to head to bed with something to read!]

I keep telling myself I should [be more involved with social media], but I just like to draw. I seem to not want to focus on that. I’m 74. I’m already set in life financially, so I’m not desperate to be making money from my art. I could do more if I wanted to. But I don’t have that kind of energy. I’m doing what I want to do in life at this point, and gardening is the other half of what I want to do in life. I use the internet for lots of reasons. I belong to Beechtree Community, a colored pencil group that gets together every Monday. We all chat about our work, different exhibits we’ve seen, new ideas, what kind of new eraser we’ve found. I use it for searching out exhibits, galleries, other people’s art. If I want a little more information about a bird, I’ll use the internet to look it up to see if I’m drawing it correctly. I use it as a reference.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It influences the landscape portion. I take a lot of photos around here. It might be a cloud, or the water in the Bay. It could be the beach where there are old piers — I’m fascinated by the wood. I always carry my phone. Sometimes I just stop the car when I’m driving. Over here on the Peninsula there’s so many beautiful areas.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

No. I knew no one at all. I didn’t have a clue how you’d get into art. After I took my graphic design program, I didn’t know how to get a job. That’s why I ended up as a paralegal. When you don’t have someone, or know someone in the field, you don’t have a clue how to get into it.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work?

I mentioned the gentleman I had for my woodcut course. He was very influential because he was so open to teaching, and helping me understand how to open my mind, and use my mind when I’m doing my art. The other person is Georgia O’Keeffe. She was one of the first artists that was a woman who was recognized. I read one or two biographies about her, and you realize she came from an ordinary background. I like what she does, and the way she did very feminine art — so different from what the men were doing. I think women have a different feel when they draw. [NOTE: Judith adds to this thought: Georgia O’Keefe always interested me because one, she was a female artist and two, a large portion of her work centered around nature and the outdoor world, which I relate to, and was created in a modern style. She became a significant female American artist who began life with a very modest beginning on a farm near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin which also seemed relatable to me. When I said I like what she does I meant that I found the way she interpreted the world through art very appealing. I’ve always found it very feminine even if she was using bold colors; her interpretations were gentle often flowing rhythmically. I’ve always felt that men don’t have that tenderness in their art.]

To whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

Beechtree Community. I do use my daughter sometimes, but she’s not available all the time. But with the Community, we do have a day every month where you can share work. There is one member who works in colored pencil. You can tell her what your problem is, and she posts it. All of us who are on [the site] that particular day can talk about how they’d [address] that particular problem. It’s very helpful. If you’re not working in a studio with a group you don’t have access to criticism and critiquing. I’m always open to it.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

When you exhibit, you get the feeling what you’re doing is valuable. Other people are seeing it’s well done, they think and feel. It encourages you to go on. You go to an exhibit, and sometimes you get inspired by other work that’s there. It helps. It’s not an easy thing to pay attention to exhibits, and send art out, but I do think it’s valuable.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I don’t know if I try to nurture it. It’s there all the time. I have an incessant curiosity about things. I’ve had family members ask me why I ask so many questions all the time? It’s because I’m fascinated by everything. I’m curious all the time, and that kind of curiosity feeds me. I read books on many subjects.

What drives your impulse to make?

I really like to draw. The first 55 years of my life, I didn’t tap into myself. I was always giving to other people and things, and I suddenly decided that I would give up all my community work, and just do what I want to do for the rest of my life. I want to do all that I can to encourage my artwork because that’s what I like to do. I feel like I’ve given a lot, but this is my time. I have 10 more years, maybe 20 if I’m lucky.

Learn more about Judith Shepelak here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.