Traverse City artist Joan Richmond responded to the COVID shutdown in her Northern Michigan town by going to work in her studio. She created 60 collages, a selection of these abstract, color-and-line composition are exhibited at the Glen Arbor Arts Center. Paper + Scissors + Glue = New Collages, an exhibition of 12 new works, is on display in the GAAC Lobby Gallery January 15 – April 22, 2021. Joan Richmond discusses how she creates a collage, what materials and tools she uses in a short video interview with GAAC Gallery Manager Sarah Bearup-Neal.

Category: Creativity Q+A

Creativity Q+A with Bob Downes

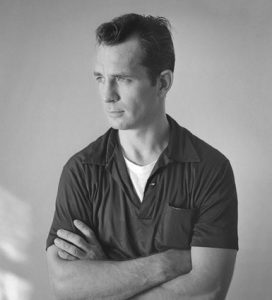

Bob Downes, 69, “always wanted to be a novelist.” And, that is what he became. Bob Downes is the essence of peripatetic. The author of seven books, many of which were written on the move around the globe, calls Traverse City his home base. He is as inspired by writers from the canon as he is by the creative energy of iconic Michigan musicians. He has written for hometown weeklies, corporate healthcare, and helped birth an alternative newsweekly that endures. Read all about it. And, him. This interview took place in December 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was a teenager. I majored in journalism in college, and have been writing for all of my adult life.

What was it, when you were a teenager, that put this idea in your head?

I read a great deal as a child. I probably read more books than any kid I ever met. We had a summer reading program every year, and I always read way more books than anyone else.

It was the act of reading that ignited your interest in the act of writing?

I thought of myself as a storyteller even when I was a child.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I always wanted to be a novelist, even in college; but I thought I’d take the Ernest Hemingway route, and get a newspaper job, as a bread-and-butter job to get me through until I started writing The Great American Novel. Journalism was my gateway drug.

You like to write in libraries and coffee shops. Why?

It gets you out of the house. It gets very boring sitting around the house all the time. For whatever reason, those [places] feel like comfortable spaces to write in.

I’ve often wondered if the clanking coffee cups, and the whirring ceiling fans, and all the conversation sounds in these public spaces end up being white noise?

When you’re a newspaper reporter, like I was for 30 years, you get used to working in very noisy newsrooms, and you just blank that out. I do have a home workspace where I do my marketing and press releases, and things like that. It’s my Command Module. It’s about 6 ft. x 6 ft. And it has two computers, and an iPad.

What newspapers did you work for?

I was editor of Orion Review in Lake Orion [Michigan]. Then I worked as a stringer for the Detroit Free Press. Then I was a reporter for the Birmingham Bloomfield Eccentric, and the Pontiac Waterford Times … That was in the late 70s, early 80s, and then I came to Traverse City to be the publications specialist at Munson Medical Center for 10 years … I was the whole meatball: I did all the writing, all the photography, all the editing and also all the press relations for Munson. I was ultimately in charge of seven publications there, including the annual report.

You’ve had a lot of in-the-trenches journalism experiences — along with corporate journalism experience.

Yes. And I was probably least likely to succeed in my journalism class at Wayne State University [graduating in 1976 with a degree in journalism, and a minor in photography].

You’ve written that you’ve completed several manuscripts on an iPad, wintering in the tropics. Talk about working any place you can plug in vs. having a designated, stationary work space.

I’ve completed several books on my iPad or on a lap top in Mexico, Guatemala. I think I finished Windigo Moon in San Marcos, Guatemala. And then I finished Bicycle Hobo in Mexico. Biking Northern Michigan I started writing in Costa Rica. When you’re writer, you can write anywhere. I’ve met people who want to become writers, and they say, ‘First, I’ve got to get a computer to write on.’ I tell them, ‘No. All you need is a pencil and a piece of paper.’ That’s all you need. When I wrote Planet Backpacker, I did what Jack Kerouac did. I just scribbled down notes on napkins and scrap paper while I was going around the world, and then I’d write [a blog post] every chance I got at an internet cafe. That’s what Jack Kerouac did when he wrote On The Road. Just with little scraps of paper he’d stuff in his backpack. He put it all together in one manic writing spree.

Being untethered to a stationary work space doesn’t seem to be an impediment to your production.

No. I’m extremely enthusiastic about whatever I’m writing, so the whole world disappears. In my two books about native people* I just completely disappear into the 1500s. It’s like I’m really there going down the Mississippi, or walking through the forests of upper Michigan with those characters.

*Follow-up | Bob writes: “ ‘Windigo Moon’ is about the Ojibwe and a little bit about their relations, the Odawa, with both tribes also known as the Anishinaabek. My new book, ‘The Wolf and The Willow’ features the same tribes, but also has chapters relating to the Dakota Sioux, the Caddo, Cahokians, Tobacco People, Haudenosaunee, Mandans and Mauvilans.”

Talk about the themes and ideas that are the focus of your work?

My themes always relate to adventure; but I seem to find a lot of inspiration from unrequited love; justice and retribution, and their cousin, revenge; and some aspect of romance related to adventure.

How many of these themes are drawn from your own experience?

I’ve certainly had unrequited love in my life. And, I’ve certainly had a great deal of adventure: backpacked around the world twice, bicycled 5,000 miles across North America and much of Europe, backpacked through all the wilderness lands of the Ojibway*. I have a very strong sense of retribution. I’ve sent two people to prison who crossed my family, which I won’t go into; but it was me, the point man, who sent them there. Don’t get me mad.

I’ve certainly had unrequited love in my life. And, I’ve certainly had a great deal of adventure: backpacked around the world twice, bicycled 5,000 miles across North America and much of Europe, backpacked through all the wilderness lands of the Ojibway*. I have a very strong sense of retribution. I’ve sent two people to prison who crossed my family, which I won’t go into; but it was me, the point man, who sent them there. Don’t get me mad.

*Follow-up | Bob writes: “Throughout northern Lower Michigan and the Upper Peninsula, and also north to Agawa in Ontario, along with Isle Royale and Upper Minnesota.”

Bob, you’re the embodiment of writing what you know.

Every writer is basically writing about some aspect of their personality. It’s not necessarily you; but it’s all drawn from your subconscious, your experience.

What prompts the beginning of a project?

Your subconscious. I’ll spend as much as several years writing a book in my head before I write anything at all. And then, you start writing, and think you know what the story is going to be, and your characters take over and take it in different directions. My latest book, The Wolf and the Willow, I thought certain characters were going to pass away, and they did not. They surprised me, and made it a better book.

I’m thinking of that phenomena, of the writing taking on a life of its own. The tail wagging the dog.

I don’t hear you say you feel like you’re taking dictation.

No. You’re taking inspiration.

How much pre-planning/research do you do in advance of beginning a new project?

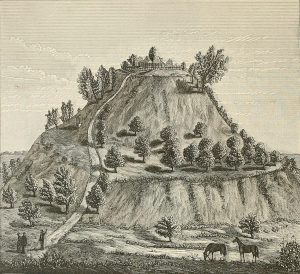

For the historical novels I’ve had a very deep dive into the history of native peoples and anthropology. I have a collection of 50 books [on both subjects]. And, of course, I’ve studied many, many others. This current book [The Wolf and the Willow] delves into the conquistadors, so I did a lot of research into them. I’ve generally visited every place I write about so I have a sense of that place. My current book, one of the key locations in it is the Great Pyramid in Cahokia in southern Illinois. I’ve been there, climbed to the top of this pyramid, been to many mound-builder sites … A lot of these place I write about I have first-hand knowledge of them in addition to reading history books …

You’re writing about things that happened in a time well before the present. So, when you’re in Illinois and looking these places, there’s a strip mall and a Wal Mart: How are you able to push the current time aside so that you can see back in time?

What’s your favorite tool associated with your creative practice?

My iPad, and the subconscious mind.

Are there other objects you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I do a great deal of bicycle riding. When you’re in a zone like that, you often come up with scraps of dialogue or inspiration. So, I’ll stop and will record on my phone what that message is. Your mental process switches brain hemispheres when you’re doing something repetitive like running or biking or meditation. I find that to be true. Some of my best insight come when I’m riding my bike, and I have to stop and record them.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

I’ve always been one to get knuckled down and get things done. I don’t get writer’s block because I don’t work on things I not inspired about … There are times when I jump out of bed at 5 am and I can’t wait to get writing. I’ve always written with “serious intent” because I’m energized by it, and inspired.

What role does social media play in your practice?

What’s social media’s influence on the work you make?

Nothing at all. I write for myself. I don’t think, “Grandma is going to be reading this, I’d better not say that.” I write what I like and find interesting.

What do you believe is the creative practitioner’s role in the world?

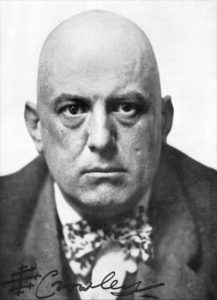

Aleister Crowley, who was a practitioner of the occult most famously, I think he considered himself a sorcerer of sorts, he said, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.” To boil that down: Do your own thing. Be true to your own self. Any artist who really succeeds is true to that. They have their own vision, and follow it over the cliff if they need to. They don’t pander to what the popular taste might be.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

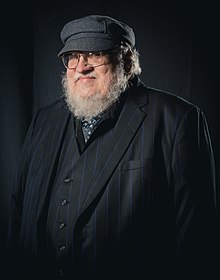

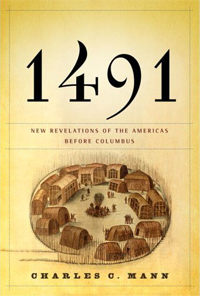

For one thing, I got very interested in native peoples … When I was a child I lived on my grandfather’s farm outside Rockford [Michigan], and my dad had plowed up scores of arrowheads and Indian artifacts in our fields. I grew up with the idea we had countless more native peoples here than we could possibly imagine, and that was true. I grew up reading all about the Indians. When books like 1491 [New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus] came out, you discover that there had been 50 million native people living in North and South America, and 95 percent of them had been wiped out by disease. Their fabulous civilizations passed away. What we seen now are the refugees and reorganizers of those civilizations. Living in this area inspired me to write more about them. Having done a lot of backpacking and endurance sports, and some pretty rough camping adventures, I was always in awe that they could survive in this relatively harsh environment. I started out writing a short story for my own entertainment in 1990 about an Ojibway hunter pursued by his mortal enemy in a terrible winter. Twenty-five years later we sold The Express and I got to wondering about that hunter, who his family was, who he loved, so I wrote another story, just for fun, never planning to publish it. My daughter told me there was a writing contest tied to the [2014] Art Prize in Grand Rapids. I threw it in the mail, and was astounded to find that I won first prize for that story. That became the first chapter in Windigo Moon.

For one thing, I got very interested in native peoples … When I was a child I lived on my grandfather’s farm outside Rockford [Michigan], and my dad had plowed up scores of arrowheads and Indian artifacts in our fields. I grew up with the idea we had countless more native peoples here than we could possibly imagine, and that was true. I grew up reading all about the Indians. When books like 1491 [New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus] came out, you discover that there had been 50 million native people living in North and South America, and 95 percent of them had been wiped out by disease. Their fabulous civilizations passed away. What we seen now are the refugees and reorganizers of those civilizations. Living in this area inspired me to write more about them. Having done a lot of backpacking and endurance sports, and some pretty rough camping adventures, I was always in awe that they could survive in this relatively harsh environment. I started out writing a short story for my own entertainment in 1990 about an Ojibway hunter pursued by his mortal enemy in a terrible winter. Twenty-five years later we sold The Express and I got to wondering about that hunter, who his family was, who he loved, so I wrote another story, just for fun, never planning to publish it. My daughter told me there was a writing contest tied to the [2014] Art Prize in Grand Rapids. I threw it in the mail, and was astounded to find that I won first prize for that story. That became the first chapter in Windigo Moon.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place? How would we see this?

Oh yeah; but a reflection of it in the 1500s.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

Just different subjects.

Did you know any practicing writers when you were growing up?

No. Just through their books. I did know my Uncle John [Downes], who was a poet. He wrote thousands of poems. I published a chap book for him called The Heartland. He lived on our family farm outside Rockford.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Uncle John. I would never have been able to go to college. He and my Aunt Lillian paid my way through college. I was a very rough-around-the-edges, stoner kid at that time, in and out of scraps with the law. Not really very together; but he continued to have faith in me, and they put me through Wayne State University, and inspired me to write.

On paper, you don’t sound like a very good investment for your aunt and uncle.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My wife [Jeannette Wildman] will always tell me what I’ve written is crap.

What gives her so much authority?

Well, she’ll just tell me something isn’t good. I had a literary agent I sent things to, and he would tell me the work wasn’t strong enough.

Besides working for Munson Medical Center, you had another, notable day job.

We [Bob and his business partner George Foster] sold The Express eight years ago. Back then I wasn’t writing anything. I did write Planet Backpacker while I was at The Express; but otherwise …. I was just focusing on writing the paper. It wasn’t until after we sold the paper got involved with writing book. And to this day, I still think of that as a hobby. It’s nothing you’re going to make a living at.

How does – or did — your day job cross-pollinate with your studio practice?

They were two different things. I segued from the paper to the authorship thing. I wasn’t really being an author when I was at The Express. After we sold the paper I was looking for something to do, and I thought I’d gamble on writing books for five year, which has turned into 10. Now I’m starting to find a little bit of success with it.

Read more about Bob Downes here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Terry Wooten

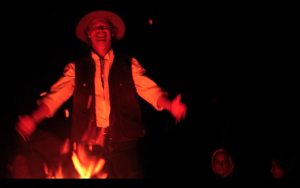

Terry Wooten, 72, is an oral poet, a bard in the truest sense. This Antrim County artist has authored more than 500 published poems, and memorized 567 poems. Until the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, Wooten regularly traveled to work with school children throughout Michigan on an array of poetry and oral history projects. And, every summer for more than three decades, he lit the fire that illuminates Stone Circle [1], an 88-boulder, three-ring circle on his property 10 miles north of Elk Rapids. Before COVID, under the summer stars, anyone who wanted could recite a poem or tell a story at these Saturday evening gatherings. Unlike the petrified stones, poetry is a living thing and a way for Wooten to talk about everything that interests him in the world. And, by the way, April is National Poetry Month. This interview took place in January 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal. GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

I’m an oral poet. I’m a performist poet.

Your work seems to be divided into three boxes: Your own writing practice, working with school children, and Stone Circle.

Actually there’s four boxes. I do the column [2] for the Record-Eagle, too. A lot of times I’ll take the prose of my newspaper columns, and after it’s published, maybe a year later, I’ll concentrate it, change it around into a poem. So I use some of those columns for poetry.

Sometimes when I’m working on a poem and I haven’t finished it, or there’s a line I don’t understand what to do with yet, I’ll perform the poem to kids anyway, and will make up something while performing the poem. After I’ve performed it three or four times, I’ll take the one [version] I like best … and that’s what will become the finished product. Also, you get a lot of insights into your poems when you perform them in the schools and Stone Circle. There might be a line the kids don’t understand, or seems vague to people, and I’ll realize I have to touch it up a bit … [Once, while] working in the Traverse City schools, [a sixth grader who] was born on Sept. 11, 1990 and turned 11 on 9/11 [September 11, 2001], told me the story of going to school and waiting for her mom to bring the [birthday] cupcakes … And it didn’t happen. She felt so violated. During my workshop, I teach kids to talk to write. I told her she should talk that and write it, and she did … I came home and wrote a poem in her voice, and sent a copy to the school. The teacher called me a couple days later and said, You’ve got to come back [to East Elementary]. The Record-Eagle has come to interview Jessica, and we want you there …

Describe your writing practice.

Very seldom do I get an idea for a poem writing at my desk. That’s where I write them, but I might be sitting out in the sun behind my garage … My granddaughter, Annie, we have a game she likes to play. She’ll sing a song from Frozen [3] and then I’ll do a poem, and then she competes with herself, jumping. One day she jumped so hard she fell on her butt backward, she got up and sat on the swing, wouldn’t look at me or cry, but turned around and said, I landed so hard my front baby tooth hit my shin. It’s loose. Now I have two teeth I can wiggle. The Tooth Fairy will be coming soon. She doesn’t have the [COVID] virus. No fairies do. I was sitting out behind my garage later that day and I thought what a beautiful insight into a 6-year-old, and how they’re dealing with the virus. Fairies are immortal. And so, I came into the house and wrote it down real quick; if I didn’t, it would disappear.

What draws you to poetry?

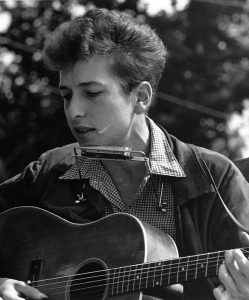

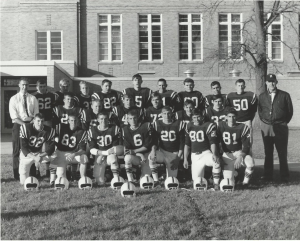

That changes as you grow. When I was a youngster — 8th, 9th grade — there was a controversy in our school about the books Catcher In The Rye [4] and Lord Of the Flies. [5] Both of those books were banned in my school. The same teacher assigned Walden [6] by Henry David Thoreau— she wasn’t even my teacher. She was in the high school. I got a copy of Walden before they banned that, too … and I read the essay “Civil Disobedience,” [7] and it really touched me — that you could disobey civilly against authority. I remember … walking down this main street in Marion, Michigan, my home town, right in front of [Marion] Hardware, thinking, I want to be a writer. I want to disobey. Civilly. [8] That was the beginning, although I procrastinated two or three more years before I really got into it. But I kept it hidden for three or four more years. I started writing about my senior year; but I was a football player, and I didn’t think that football players were supposed to write poetry. One of the messages I give high school kids is: Go ahead. If you’re a football player, write poetry.

Did you receive any formal training?

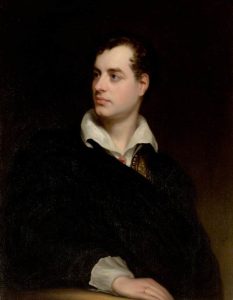

No. Other than that one teacher who assigned those books. She was a closet beatnik. Didn’t last too long in my hometown. She was too progressive. She opened me up. She insisted you write your own feelings, and I became addicted to that idea. I only lasted two years in college because my family couldn’t afford college for me. After two years, I quit Western [Michigan University], but I had this attic apartment that my boss-friend [rented] to me for $40 [a month]. I used the university library. I went through a heavy Shelley/Keats/Byron [9] phase, and then I remember when Ezra Pound [10] passed, I went up to the library to look Pound up, and was blown away by the Imagists [11] — some of the first poets besides Walt Whitman [12] who didn’t rhyme … I lived in that attic apartment for seven years in Kalamazoo and read voraciously. I was just fascinated by lines. I even keep notes in lines. [13] I’m somewhat dyslexic, so the line structure and the stanza structure makes my poems a lot more accessible for my eyes. I’m writing more now, more than I could memorize.

You immersed yourself up in the attic, and read, read, read.

Yes. It was a nice little apartment. I have fond memories of it. Sometimes I wish I could go back there and stay there for a week.

Describe your present studio workspace.

I have a wood stove. And I built the stone wall behind it. I have three, 4 ft. x 8 ft. bookshelves. I have a window looking out west, and there’s a lot of boulders out there. I’m into visual feng shui. I love the arch of them. Behind that is a white pine forest. I’m constantly watching deer walk by. Squirrels that drive me nuts. There’s a bird feeder. To the left of the wood stove is a big glass door so I can step out. I have three pear trees out there. I’m constantly watching deer, coyotes, porcupines … It’s about 16 ft. x 24 ft. [interior].

It doesn’t sound like your studio space is confined to the four walls of that room. It sounds like the outdoors is as much a part of your work space — at least in your mind.

Yes. I’m an outdoor person. I’m not well suited to be a writer. You’re not going to catch me at my desk all day long unless it’s bad weather in the winter, and I’m transcribing interviews for my Elders Project [14].

What is the work that happens in that studio space?

Very seldom do I do any memorizing in here. Most of my memorizing is done outside when I’m doing odd jobs around the farm or my home or my mother-in-law’s [15]; but once I get the idea for the poem, or a few lines, I work on my computer. I do most of my composing on the computer. I’ve taken to writing a lot of haikus during the pandemic, and usually I write them out on a piece of paper, and type them out.

What is about the pandemic that has prompted a lot of haikus?

They’re healing. A lot of people really like them because you can remember the beginning by the time you get to the end. Sometimes with a 30 or 40 line poem, you have to read it a few times; you have amnesia, and forget as you go down the poem.

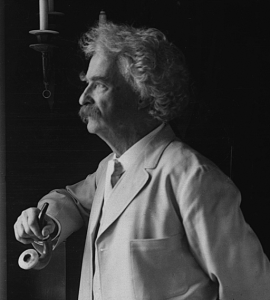

They’re healing and uplifting. A lot of people are dealing with a lot of anxiety and depression. Even as I’m writing something that’s serious, I try to keep it upbeat. I love to use humor. Mark Twain [said] that one of the greatest thing we can do about the human situation [is] that we’re here, and we really don’t know why we’re here, and not going to be here someday, and one of the greatest weapons against that is you can throw your head back and laugh.

Does your workspace facilitate your work?

I do a lot of pacing when I’m writing. And this big glass door is nice. You just get up and stare out the window. I can see the Stone Circle from my room. So it gives me room to walk around in.

How is pacing part of your process?

I’m writing when I’m doing that. I’m constantly composing and memorizing. I like to observe people. And before I became really well known, my wife [Wendi] used to get this question: Now, what does your husband do? It doesn’t look like I’m doing anything. I might be standing on the street, listening to people. I hear the human voice like music. Sometimes, something will come out of someone’s mouth, like: Get a job! When I mowed over my wife’s grandmother’s flowers by accident, she said, What’s wrong with you, you’re a poet. Poets are supposed to love flowers, not mow them down. And that, of course, became the idea for a poet: “What’s Wrong With You.”

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

My themes go all over the place. The first few years, when I was young, the theme was myself, my experiences. [Other ideas came out of] the Elders Project. I would bring 8 – 10 elders from the community into the school, and I teach the kids how to interview them, and the kids will listen to the tapes, and take one story and transcribe it. You never know what the elders are going to tell you about … Sometime I run into veterans. There were two teachers in Elk Rapids and they’d both been at Iwo Jima and they didn’t know because they didn’t talk about it … When I was listening to the tape, transcribing it, one of the guys got really shaky. When I found out about this, I called him and asked if I could come over and talk to you about this? It was the beginning of a good friendship. I wrote a whole series of poems on Iwo Jima and his battle experiences. He was on the beaches for five-and-a-half days with what they called a “Beach Party Group.” It wasn’t hot dogs and potato chips. They worked with explosives … He lost his rifle in the first five minutes.

The themes that are the focus of your work could be anything.

Yes. You just don’t know what’s going to come out of someone’s mouth … I got started on the Elders Project by interviewing my wife’s oldest uncle, who was on the Baatan Death March [16]. They were always told not to ask question it. I ended up doing five or six interviews with him, and ended up writing a book called Lifelines. It healed him. He’d never gotten those words out. He’d carried those words around with him for 60 years, and it changed him; but it depressed me …

It sounds like you need to be a very present listener, or you might miss something.

I use tape recorders … I have a friend who produced a film about Stone Circle [17] but he said the first time he met me he had the sense I was very, very aware of the space around me. I guess I am. I hear voices. It doesn’t have to be a World War II veteran who experienced the Baatan Death March. It could be a little girl telling me about how fairies don’t have the virus. All conversation has that potential for a poem.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

When I write my own poems, very little pre-planning. An idea might just come to me, or something will happen that I’ll want to entertain. With Elders Project — a lot; I have to teach the kids how to interview … Then I have to transcribe the recordings. Once I get all the rough prose down I put switch things around … There’s a lot of satisfaction in taking someone else’s story and turning it into a poem of it and giving it back to them. It helps them tell their story. A lot of them can’t write … It’s healing, although it can be dangerous for me.

Do you work on more than one poem at a time?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no.

Visual artists sometimes have more than one thing on their studio wall. When they hit a block, they’ll move over to the other things, and work back and forth.

I don’t do that so much. I have things in a folder, and I’ll pick things out. I go through phases.

What’s your favorite tool?

Pencil and paper and computer. Another one of my tools is my voice. Just saying the poems, and using your ears. I’m efficient with paper [he cuts an 8 ½” X 11” sheet into quarters, and writes notes on a quarter]. I’m just writing down the initial idea, and then I’ll switch to computer.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

I was 18, 19, my freshman year in college. I was already doing things I wasn’t supposed to. I was supposed to be doing my homework, but I was writing a poem instead.

There are two rules at Stone Circle: No swearing, and poems must be recited by memory. Why by memory?

You can swear down at Stone Circle, but I don’t want the big bad swear words. It depends on the audience, too … As far as the memorization, rules are made to be broken. If a little girl or boy would come to Stone Circle with a poem he or she was going to read, and I said you can’t do that, it would cause more damage than good. I do allow some reading, sometimes.

Why is reciting poetry valued at Stone Circle?

You really get to know a poem … when you memorize them. I take a poem on a piece of paper and carry it around in my back pocket and memorize one or two lines a day. As you’re memorizing a poem, you might realize that a word isn’t working right, or you don’t like the rhythm, and I’ll change that …

Memorization has something to do with embedding the poem into your DNA.

For a while you see the words, and after a while you don’t see the words. It’s just there. It’s interesting — you mention the word DNA … I think fire and telling stories is in our DNA. When people come to Stone Circle you can’t sit around the fire and not want to hear stories. It’s there. We’re wired that way.

There’s a lot of competition for people’s attention today. We’ve moved from making our own entertainment to consuming it. How does Stone Circle stand up in the 21st Century?

It’s something about sitting around on those boulders, in a communal atmosphere and listening to those words that sound like songs and seeing the pictures in your imagination — it pulls us back to an early time. What goes on down at Stone Circle could be 40,000 years old. When we captured fire, it expanded our time. And when we expanded our time, we didn’t just curl up when it got dark. We started sharing stories. There wasn’t TV. There wasn’t radio. And with language came stories and poetry. It’s almost like a psychedelic experience: expanded consciousness. I think people, whether they realize it or not, when they’re down to Stone Circle, it’s something really old that touches them. Some people — they’re not so impressed by it. Fire is a very simple tool, but it’s very old. Consciousness and language have grown up together.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Very little. Every now and then I’ll post a poem on Facebook, just to say, Hey! I’m still out there. It’s kind of like frogs singing in a pond. There’s a January poem I post every year, and people have come to expect that. I post my [Record-Eagle] columns.

How did the column come about?

I wrote the editor of the newspaper and told him about my Elders Project, and asked for a column to expose that. That’s how I got started. I own my columns. I can’t give away the copyright to my art.

What do you believe is the writer’s/poet’s role in the world?

Percy Bysshe Shelley said writers are the unacknowleged legislators of the world. I like what Gary Snyder [18] said in his book The Real Work — that we give voice to animals and critters. They don’t have a voice. I can write and give those animals a voice. They have spiritual rights. To me, it’s the poet’s job to give voice to the birds, to the wooly worms, to the frogs — as well as the other people who don’t write and can’t share their stories.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

I write in lower Northern Michigan, so a lot of that appears as a background in my work. I think rural Michigan is my voice. I write in that vernacular, too.

Did you know any practicing poets / writers when you were growing up?

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Two people. Undoubtedly, Max Ellison [19], who recited his poems by memory. I met him Labor Day Weekend in 1980, and had 20 poems memorized by the next weekend. He blew me away. And, Glenn Ruggles, [20] an oral historian who was recording voices and writing down in interviews. There wouldn’t be an Elders Project without Glenn Ruggles …

You’ve incorporated elements of both these people’s work into your own practice: reciting by memory and recording oral histories.

Max — I’d never met anyone who recited poetry like he did, or made a living at it. I’d been writing for 25 years and still struggling, I had a little boy, and working on my wife’s [Antrim County] family farm, but within four years I was making a living as a poet. Unfortunately Max passed. Glenn opened me up to oral histories, or HERstories. It’s not just HIS story; it’s HER story, too …

What was it about connecting with Max that put a booster rocket under your poetry practice?

I just didn’t know you could make a living outside a university. And, because I didn’t have a degree, I was being shunned by university poets. Max had been working in schools for years. When he passed, everybody just picked up on me, and invited me [to teach poetry in schools]. One of the reason I dropped out of college, other than there wasn’t a lot of money, is there was a [required] class [in which] you had to teach people how to write and sing a song and get up in front of an audience. I quit the class, and here years later, I make a living as a professional speaker. Where’d this come from? Max.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

That’s easy: My wife. I get mad at her half the time. Especially my columns. She criticizes them, and at first I’ll be disgusted, but then realize she’s right. Not much with my poetry. Feedback for my poems comes from my audiences. I have an advantage over other poets. I’ve been touring for some 30 years in schools and Stone Circles, conferences, and festival. There’s built-in feedback.

Beside the feedback you receive from audiences, what is the role of the performance in your practice?

It makes the poem come to life. If you do write something down, it’s there. But if you say to them, there’s the power of the oral tradition: You pass them on … Someone asked me once why I broke with tradition by doing my poems orally. I didn’t break with tradition. It’s very old. Chaucer [21] went to Italy and discovered The Decameron tales [22]. He memorized them went back to England and wrote The Canterbury Tales. He couldn’t have done that without the oral tradition. People have passed things down for thousands of years through the oral tradition … There’s a power to the spoken word. I catch that too with my Elders Project. The people say the stories, I transcribe them down into poems, then you turn around and re-memorize them and put them back into the oral tradition. They’re more crystalized. Tightened up. When I teach kids to write, I talk about power words and nerd words. Nerd words are words like: and, really, very, almost, about. Try to get rid of as many of those as possible. Power words are: turtle, trout, belt.

Do the power words hold up better when spoken out loud?

Yes. When you write something like: That’s pretty tough. It’s not “pretty”; it’s tough! We’re sloppy like that when we talk. [When teaching kids] I compare it to making maple syrup. You’re tapping into yourself or you’re tapping into an elder. You’re getting the sap, and you boil it down during the writing process to get the poem …

Will Stone Circle return in 2021 after going on COVID hiatus in 2020?

I hope so. I was at a loss last year. Depends upon the new strains of the virus. I don’t want Stone Circle to end because of the pandemic. We did three or four small [Stone Circle gatherings] last year, but it’s not the same as when you get 100 people. A lot of our audience come from hot spots downstate. You could social distance down there, but at the same time, I blast, I push the words out in the air. It just depends on the pandemic ….. and the red shouldered hawks. If they start nesting down there, it’s going to be a real problem. Two years ago we had some Red Shouldered Hawks build their nest about the Stone Circle wood pile. They’re aggressive birds. I talked to Rebecca Lessard [23], and she said to acclimate yourself to them. Talk to them. Take a radio down there and play it. Recite poetry to them. I still got dive-bombed five times. It’s like being buzzed by a 10 pound hornet … That’s the only times we’ve been closed — for Red Shouldered Hawks and COVID 19. I’m still healthy. I’m a year older than Max when he passed, and that’s a sobering thought, but the fire still burns in me … Not bad for a football player.

Footnotes

1: Read about Stone Circle here.

2: Terry Wooten’s Traverse City Record-Eagle column is Lifelines. It is published the third Sunday of every month in the Northern Living section. He began writing the column in 2010.

3: Frozen is the 2013 animated Disney film based on the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale “The Snow Queen.”

4: Catcher In The Rye is a novel by J. D. Salinger, partially published in serial form in 1945–1946 and as a novel in 1951. It was originally intended for adults but is often read by adolescents for its themes of angst, alienation, and as a critique on superficiality in society.

5: Lord Of The Flies is a 1954 novel by Nobel Prize-winning British author William Golding. The book focuses on a group of British boys stranded on an uninhabited island and their disastrous attempt to govern themselves.

6: Walden is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings. It was first published in 1854.

7: “Civil Disobedience” was published in 1849. In it, Thoreau argues that individuals should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy an individual’s conscience, and that they have a duty to avoid acquiescing to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice.

8: Terry writes: “You’re not supposed to be able to make a living with poetry without working at a university or academy … Being a folk or peoples’ poet was my form of Civil Disobedience. The essay also came in handy when I was resisting the Vietnam War. I was drafted three times, kicked out of Fort Wayne and finally visited by an FBI agent. Turned out my draft board had broken as many laws as I had, and the FBI got me a deferment. Recently I wrote a few poems about my resistance.

9: Percy Bysshe Shelley [1792-1822], John Keats [1795-1821], George Gordon Byron [1788-1824], all English Romantic poets.

10: Ezra Pound [1885-1972] was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II.

11: Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language.

12: Walt Whitman [1819-1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism.

13: Terry writes: “Strong lines of poetry were also something I wanted to emulate. When I was trying to write Lifelines, the story of Jack Miller’s experience of the Bataan Death March and being a POW for the entire war, the story was so gruesome I had to find a more accessible form or eye friendly structure. I started breaking the poems up into stanzas and varying the lengths of the lines. This makes the poems more eye friendly and less intimidating to the reader.”

14: The Elders Project uses oral history interviews to create poetry based on the stories and lives of elders in the community. It was initiated in 2003. In 2013 it won the State History Award in Education from the Historical Society of Michigan.

15: Terry writes: “In 1975 I married into family of [Antrim County] cherry farmers. They also grew peaches and apples. A year later I started working with McLachlan Orchards. It was a big farm, and I spent a lot of time alone trimming trees, picking up rocks and roots, or thinning peaches. It wasn’t all that inspiring unless you had a poem in your pocket that you were memorizing. Early on I memorized a lot of poetry that way. Before long I started working full time performing poetry. My father-in-law and his two brothers have all passed on now, and most of the land has been sold. But there are still two barns and three other building to keep up and grass to mow. I call this “the farm,” but I never really considered myself a farmer. All the boulders for Stone Circle came from my wife’s family farm. I also help my 90-year-old mother-in-law with her house and lawn. I don’t memorize as many poems as I used to, but I have to keep polishing them up, while working on “the farm” or working around my own house. If I don’t they will fade away.”

16: The Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of 60,000–80,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war onto trains. The transfer began on April 9, 1942.

17: The Stone Circle, a 2017 documentary written, directed and produced by Patrick Pfister.

18: Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gary Snyder [b. 1930] is known as the “poet laureate of Deep Ecology.” In his 2015 book The Stone Circle Poems, Terry writes: ” Influenced by … Gary Snyder’s vision of a poet in a more primitive sense, a sort of cultural adhesive that helps hold a community together with its stories, I started building my own poetry forum, which I called Stone Circle.” [p. 20]

19: Max Ellison, Bellaire, Michigan bard and the unofficial poet laureate of Northern Michigan, died in 1985. He was 71.

20: Glenn Ruggles taught for 35 years at Walled Lake Central High School. He was a renown oral historian who summered in Grand Traverse County.

21: Geoffrey Chaucer [c. 1340s-1400] was an English poet and author. Widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages, he is best known for The Canterbury Tales.

22: The Decameron is a collection of novellas by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio [1313–1375]. The book contains 100 tales told by a group of seven young women and three young men; they shelter in a secluded villa just outside Florence in order to escape the Black Death.

23: Rebecca Lessard is a Leelanau County raptor rehabilitator and expert. She is the founder of Wings of Wonder, a raptor education center.

Learn more about Terry Wooten here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Karen Anderson

Karen Anderson came “out of the womb searching for meaning.” The Traverse City writer has found it in a bowl of oatmeal, buckle snow boots, canoeing the Manistee River, and the historic neighborhood in which she’s lived for several decades — among other places and things that, at first blush, seem mundane. But it is this very ordinariness about which she writes that has spoken, clearly and loudly, to readers of her newspaper column, and now to listeners of her weekly radio essays. Karen Anderson’s love affair with words and ideas has been part of the locality since the 1970s; and continues — in spite of a college professor’s lament that marriage, motherhood and all the rest might diminish her creativity. This interview took place in January 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work. What is your work?

Currently, my medium is radio, and I contribute weekly essays to Interlochen Public Radio.

How many books have you published and what are their titles, publication dates?

Three: Letters from Karen in 1978; A Common Journey in 1982; and Gradual Clearing: Weather Reports from the Heart in 2017.

How many essays have you written and read on IPR?

I started contributing a weekly essay in 2005. So, if you do the math, it’s weekly … 52 a year times 15 -16 years, whatever that is.

How long did you published essays in the Traverse City Record-Eagle?

It was a weekly column, and I did that for 30 years. I was invited to start writing a personal column in 1973, and continued until 2003. Then, Peter Payette [then News Director, now Executive Director] at Interlochen called me up and said, “Your columns could be adapted for radio. Would you be interested?” And by then, I really was interested in trying a different medium. I’d been doing the Record-Eagle for a long time. I really love IPR … I felt like this would be a new growth opportunity. And it was, and is.

What are the difference between writing for print and writing for radio?

I had to learn that, and thanks to Peter Payette, he could be my coach. When I wrote for the Record-Eagle, my columns were about 700-words-a-piece, and my essays for Interlochen are only 200 words. They slide them into a two-minute slot between news stories. That’s a big drop in words, so you have to condense dramatically. I learned a number of things. One is: You can really only include one idea per essay. You can’t really ramble around and add ideas and detours. There are no detours in two minutes. Another thing: Your sentences need to be short because people are listening. They don’t have text in front of them like when they’re reading the Record-Eagle. They’re listening. And if they miss something, or if your sentences are too complex, or your words are too big and unfamiliar, it’s going to go by them, and you can’t go back. Simplicity — both in terms of concept, and I don’t mean simplistic, [but sentences that are] straightforward, with focused ideas, short sentences, sentences that are clear, without lots of adjectives or dependent clauses. Here’s the thing I learned: I take out words; but I can add in with my voice what I take out in words. I can add inflections, and pauses, and emphasis that I can’t do in print. Even though it’s shorter, I really like being able to use my voice. It’s a way of indicating to the listener what I care about. With radio, there’s an intimacy about it. From time to time IPR gets people in from NPR to visit the station and coach the staff. I worked with a woman years ago … and she talked about how intimate radio is. It’s helpful if you think that you’re just talking to one person. You don’t imagine yourself talking to a thousand people. And, probably most people are listening alone. I like the immediacy and intimacy of radio, which is different than print.

IPR gets people in from NPR to visit the station and coach the staff. I worked with a woman years ago … and she talked about how intimate radio is. It’s helpful if you think that you’re just talking to one person. You don’t imagine yourself talking to a thousand people. And, probably most people are listening alone. I like the immediacy and intimacy of radio, which is different than print.

What draws you to writing, to the written word? Why did you choose writing as a vehicle of creative expression?

Because I learned early that I was good at it. I was an avid reader, and I started writing terrible, youthful things, essentially copying The Secret Garden as if it were my own novel when I was in the 6th grade. When I was in 10th grade, the assignment was to write a personal letter, and I wrote one that I made up. I made up a family in which I had an older brother who could fix me up on dates. The teacher gave an “A” on this and read it to the class. She liked it because it had so many personal details, and it was so conversational. She seemed to think I had a talent for writing, and I think that gave me some confidence and focus about going forward in that realm. I was also in art classes, and I had a small amount of talent in visual art; but it didn’t interest me as much as writing. I was hungry to ferret out the meaning of life, and I felt like words were my vehicle, metaphors and language always attracted me. That was the path I followed.

Did you receive any formal training in writing?

I majored in English literature at U of M, [Karen received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan in1966] wrote lots of papers, and went back and got a master’s degree in English literature [late 1960s]. That was some formal training. I had some really good coaching from one professor. We had to write a paper on Byron. I didn’t know anything about Byron, so I went and got a bunch of book about Byron from library. I wrote a paper quoting all the experts on Byron, and got a “C” on my paper, which shocked me. This is my major. So I went to see the professor, and he said, “I don’t want to read about what the experts think about Byron. I already know that. I want to read about what you think about Byron.” Oh my god. I didn’t have any thoughts about Byron, but he gave me permission to have ideas about something that he thought might be valuable. That was really important to me. Trust yourself.

How did your formal training affect your development as a writer?

It made me a good writer. Writing academic papers for high-quality professors is rigorous, and I learned how to express myself in a grammatically correct and beautiful way. I was taking a Chaucer class … We could write either a creative or research paper. Of course, I wanted to do a creative paper, so, I decided to make up an additional Canterbury Tale pilgrim. I made up my own pilgrim to add to the gang that was going to the cathedral. I wrote my paper in iambic pentameter rhymed couplets It was quite a few pages of single-spaced rhymed couplets, and I had so much fun doing it. My professor gave me an A+, which was thrilling. He said [I] seemed to have a gift for writing. Here’s the awful, additional thing he said. We’re talking about the 60s now. He said, “You seem to have a real gift for creative expression. I hope, when you get married and have children, it won’t dissipate your interest in intellectual pursuits,” or something like that.

How did that comment, in retrospect, influence how you went forward in the world with your writing?

Here’s the embarrassing thing: I was so thrilled that I got an A+, and that he said I was a really good writer, that I didn’t feel sufficiently offended by his additional comment that my path to motherhood and marriage would dissipate my intellectual pursuits. I never believed that; but I wasn’t as offended as I would have been after the Women’s Movement brought to my attention the ways in which the patriarchy has shaped our world. Consciousness raising was on the horizon; but it wasn’t there. I look back on it now, and I’m just appalled that he would even [say] that; and worse, that I didn’t object; but the other messages were valuable to me.

Beyond your formal training, what are the other ways you learned about your craft?

I attended the Bread Loaf Writers Conference in Vermont [1977-79, 1983 as a Bread Loaf Fellow] … It’s an extraordinary experience. It was two weeks of listening to top-notch writers read from their work, and then you attend workshops on craft, and then you can have your manuscript read by writers on staff, and meet with them to get feedback. All of those things were enormously helpful to me. It was nitty-gritty writing … I remember Hilma Wolitzer saying that her editor would go through her manuscripts and circle the words she’d repeated. That’s really good advice. Read your stuff out loud to yourself, and you’ll hear all the repetitions and the things that don’t make sense. I ended up going to Bread Loaf four times. One time, after I’d published a book of columns, I was there as a fellow, which meant I got to read from my own work, which was a great thrill. And, I got to go to Bloody Mary pre-lunch gatherings with the writers. I got as much help from those experiences at Bread Loaf as I did from U of M studying formal literature. It always helps to go to conferences and workshops where there are opportunities to get feedback on your work.

I had another good experience there, an ah-ha! moment. In my Record-Eagle columns I used to include a quote from a famous person at the beginning of the column, that was related to the topic. Writer Geoffrey Wolff was the staff person who reviewed my first book. He really liked my essays. He said, “These quotes you have at the beginning of each essay don’t add anything.” He said, “You’re hiding behind the quotes as if you needed an authority to prove your idea was valid. Your ideas are strong enough. You don’t need those quotes. They’re just a distraction.” I was scared to take them out, that my readers would protest. But I took them out and nobody even mentioned it.

Describe your studio/work space.

It’s nothing special. It’s my daughter [Sara’s] bedroom. When she left for college I grabbed her bedroom for my office. It’s just a bedroom with a twin bed, and the Cabbage Patch dolls are on the bed.

How does your studio/work space facilitate your work? Affect your work?

It just gives me privacy. A place where everything is available.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

I write about my own experiences. Daily life. Ordinary experiences. Also: nature — I write quite a lot about doing things outdoors. I write about relationships, and often a theme is the search for wisdom, or insight about the meaning of life. That sounds grandiose. Trying to extract meaning from my daily experience is the effort, the energy behind the essay.

You’re heard weekly on Interlochen Public Radio. Characterize these essays you write and read on air.

You’re heard weekly on Interlochen Public Radio. Characterize these essays you write and read on air.

They’re brief meditations on my experience and search for meaning. The subtitle of my book [Gradual Clearing], which was suggested to me by a writer friend, it’s Weather Reports From The Heart, which is a little corny; but does suggest what I’m after.

The Interlochen Radio essays are two minutes in length. What are the challenges to expression and writing posed by such a compact “space”? How do you craft an idea for such a compact space so that you can take the idea through its full arc?

Quickly. There’s one idea. Short sentences. Simple words. Focus. Focus. Plus, a kind of intimacy. That’s the construction of them. That content is, I’ve tried to be willing to be vulnerable, to be confused, to not have answers, to share from personal experiences in an honest way. Here’s the thing, and this is from the time I started writing columns in the Record-Eagle: When people talk to me about my columns, or now, my essays, they don’t talk about my experience, they talk about their experience. They’re really not interested in my experience except as it connects them to their own experience or insight or understanding. So, they come to me and tell me about themselves, which is wonderful. It’s like we’re more alike than we are different. And, people connect to what I write in ways I could have never predicted.

The confined spaces of your former column, and now, the radio essays, impose boundaries and limits on your writing. I wonder if these confines are humbling, if they remind the writer that every word isn’t precious?

I don’t think they’re humbling. I think they’re challenging. Another formal and informal training that was helpful to me is writing poetry. When my granddaughters were home schooled, I offered to teach the poetry curriculum. So, every week for seven years, they came to my house. I decided I should get more serious about writing poetry, and I took a class at the [Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City, Michigan] with [Leelanau County native] Holly Spaulding, and discovered how difficult poetry is to write. It’s even more distilled than my essays. It condenses things down even further at its best. That was really helpful. You find you can leave out a lot of words you thought you couldn’t leave out. It doesn’t take away, it adds to. You get right to the heart of things. I confess now that I’m very impatient with people who cannot be brief, either in writing or in speaking.

Are the essays you published in the Traverse City Record-Eagle different in any way than the ones you’re writing for and reading on the radio?

They were longer, so I had time to meander and include various additional thoughts and ideas. They weren’t as focused. When I started writing them, I was in my 20s. We’re talking not quite 50 years ago. I didn’t know nearly as much as I know now. Here’s the other thing: When I first started writing my column I was the “roving reporter.” I would write about fun activities around town, and then I might throw in one about my grandmother. The ones that people liked were about my grandmother. I learned from my audience that people really liked personal stories. My maturity level, my self-awareness, my repertoire of experiences were much less in the 70s than they are now. The goal is the same — to extract meaning from my experiences — but I think that I’m better at it because I know more about myself and about writing.

Who is your audience?

Right now, it’s the IPR listeners who are in Northern Michigan, and all over the place. When my book of essays was published in 2017, the audience expanded further. Not necessarily people who can hear me, or who have ever heard me, they discover my book … I really feel privileged, truly, honored and grateful to have a weekly audience. It’s a very precious thing.

What kinds of clues have you gotten along the way that tell you who your audience is?

I think it’s evenly men and women. I get letters, emails, comments out in the community. For example: When I was writing a weekly column in the Record-Eagle, my picture was in the paper every week, so people would recognize me when I was out around town. Now, people recognize my voice. It is the strangest thing. My husband and I were at a nursery buying a Maple sapling for the backyard, and the forester telling me about the tree said, “Oh, I know you. I listen to your essays on IPR.” He recognized my voice, which is fascinating when you think how distinctive our voices are. I have those experiences quite often … When I published my book and I went out and did readings — it was weekly, for a year I was out on the trail — there were as many men as women in the audience.

What do you do with the feedback you get from your readers and listeners?

I use it. Depending upon what it is. Knowing what they like is a good clue to themes and points of view resonate with people. If they don’t like it, I can use that, too — if I think it’s valid … I write a variety of essays. One recently was about oatmeal for breakfast. Now, that’s pretty mundane. Right? It wasn’t profound. I got more response to that oatmeal essay than I’ve had in quite a long time. People weighing in on how they like their oatmeal. It was humorous to me. I could never have predicted that, and I loved it. It’s a reminder that ordinary life that’s where we live, day-to-day, in our kitchens eating oatmeal. It reinforces my belief that ordinary experiences can connect us. And I just don’t mean describing oatmeal. Usually there’s some level of understanding or humor or insight about daily experiences. It delights me to find what people particularly enjoy because it isn’t often what I expect.

I use it. Depending upon what it is. Knowing what they like is a good clue to themes and points of view resonate with people. If they don’t like it, I can use that, too — if I think it’s valid … I write a variety of essays. One recently was about oatmeal for breakfast. Now, that’s pretty mundane. Right? It wasn’t profound. I got more response to that oatmeal essay than I’ve had in quite a long time. People weighing in on how they like their oatmeal. It was humorous to me. I could never have predicted that, and I loved it. It’s a reminder that ordinary life that’s where we live, day-to-day, in our kitchens eating oatmeal. It reinforces my belief that ordinary experiences can connect us. And I just don’t mean describing oatmeal. Usually there’s some level of understanding or humor or insight about daily experiences. It delights me to find what people particularly enjoy because it isn’t often what I expect.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

It depends on what I need, whether it’s the actual sentence construction or themes. I’ve always gotten good feedback from Peter Payette at IPR; from my poetry teacher Holly Spaulding, who helped me edit the essays in my most recent book. She’s absolutely relentless and fearless about taking things out. I always valued her feedback. [IPR Program Director] Dan Wanchura is the guy who produces my essays for IPR. I send him ideas before I write the essays, and he’s very honest about whether he thinks [an essay idea] has has legs, or not, or how it might grow legs. From time-to-time, I’ve had a writing group. I was in a writing group for a couple years with several really talented, regional/Northern Michigan writers, and they also helped me put my book together. I can still go to any one of them for counsel, if I need it.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

A whole bunch of things. Experiences. Overheard conversations. Sometimes a memory because I write about my childhood. I recently wrote about my brother getting to wear buckle boots when he was a little boy. I didn’t get buckle boots because I was a girl. I had to wear those dorky zip-up boots with fur around the top. It was partly a meditation: I’d perceived that things were already better for boys than girls. I had so many men telling me about their memories and experiences with buckle boots. Childhood is a rich source of memories and ideas. Books that I read, conversations I have, daily life, which keeps happening. Then I try, like many writers, to quick jot down the idea. I only need the idea. I get it on paper, in little notebook, and then I can revisit it when I have to write a batch. I write about 12 [IPR] essays at a time. And, then I go tape 12.

A whole bunch of things. Experiences. Overheard conversations. Sometimes a memory because I write about my childhood. I recently wrote about my brother getting to wear buckle boots when he was a little boy. I didn’t get buckle boots because I was a girl. I had to wear those dorky zip-up boots with fur around the top. It was partly a meditation: I’d perceived that things were already better for boys than girls. I had so many men telling me about their memories and experiences with buckle boots. Childhood is a rich source of memories and ideas. Books that I read, conversations I have, daily life, which keeps happening. Then I try, like many writers, to quick jot down the idea. I only need the idea. I get it on paper, in little notebook, and then I can revisit it when I have to write a batch. I write about 12 [IPR] essays at a time. And, then I go tape 12.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

Not much. I’ve been doing it so long. All I need is the idea. It’s like Hemingway saying begin by writing the truest sentence that you know. All I need is an image or a sentence and then it writes itself, not always well. I don’t want to know what the end is. I don’t know where I’m going to arrive because I trust the process to take me where it needs to go. If I already have an ending in mind, I often get derailed from it, and it isn’t as strong as letting the material go where it goes.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Yes. I might have several essays in various stages of development. Sometimes, I will start to write and find, for whatever reason, the stars are misaligned, and I cannot write a coherent sentence today. It just won’t happen, and I could sit here all day and it just wouldn’t change. So, I leave it, and then the stars realign, and the next day the sentences come to fruition. Sometimes I just have to leave a piece, or the idea, or I can’t figure out the ending, so I just have to leave things and revisit them, so I can work on other things while I’m waiting.

What’s your favorite tool?

I just write on a PC pretty much. Computer keyboard.

You didn’t come out of the womb writing on a computer keyboard, so talk a little bit the difference between writing by hand with a pencil and paper versus the word processor/laptop.

I used to write everything longhand on legal pads. But the computer arrived, and I was working full-time in public relations and marketing at Northwestern Michigan College. That was my full-time job, and I had to learn to use the computer for my job. I soon learned how much easier it was to revise things on my computer than it was any other way. My work forced me into using a computer.

I used to write everything longhand on legal pads. But the computer arrived, and I was working full-time in public relations and marketing at Northwestern Michigan College. That was my full-time job, and I had to learn to use the computer for my job. I soon learned how much easier it was to revise things on my computer than it was any other way. My work forced me into using a computer.

What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I make notes in a little notebook. And if I just have an idea for an essay, it’ll go into my notebook if I’m out and about. Or, I grab a scrap of paper, or a receipt from Meijer. It could vanish if I don’t write it down. My file of essay ideas is full of scraps of paper.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

When I went to work at the Record-Eagle in [the early] 1970s. It was just job, like a Gal Friday. I was reading proofs, and doing grunt work in the ad department. But I approached Bob Batdorff, who was the publisher then, and I said, “You don’t have any book reviews in the Record-Eagle, would you let me write some?” He told me to write a few and I did, and they liked them, and after they’d used a half dozen he said, “You’re a good writer, would you like to write a weekly column? Just your own. Whatever you want it to be.” It was an extraordinary invitation. At that moment, I began to think how I could shape something that was my own idea, that wasn’t about somebody else’s book or life. I started writing a weekly column for the Record-Eagle in 1973. That was the beginning of taking myself seriously as a practicing writer. And they paid me.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Not very much. My essays for Interlochen are part of their website. I have my own page where they archive my essays; but I don’t Twitter, and I don’t have my own website. I’ve thought about creating one, but I just haven’t done it.

What do you believe is the creative practitioner’s role in the world?

I think of Holly Spaulding when she was teaching us poetry, and she would say, “Make it fresh.” I think our responsibility is to take whatever ideas we have, and make them fresh so that someone looks at them anew, so that they a reason to pay attention … to any concern, insight, or wisdom we have to offer them. It depends on your purpose, if you’re trying to persuade people of something, or to enrich their daily lives. The other thing I’ve talked about before: Connecting with other people. Demonstrating how we’re all more alike than different. That we can bond over oatmeal. That there are commonalities in the human experience, which are really nourishing to consider and celebrate.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

My neighborhood: I live in Central Neighborhood in a 100-year-old house. I love this old neighborhood. I feel at home here. And, also, the larger outdoors — my husband and I go canoeing and camping and hiking in this region and beyond. Those things also really nourish me. That whole small town thing. Traverse City is a small town in some ways, and I like that.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s an accessible place. Even though we have a lot of new people moving in, I can still walk downtown and see people I know and chat with. I can talk with Jim Carruthers, the [former] mayor of Traverse City who bikes by my house. There’s still a sense, since I’ve lived here a long time [since 1984], of knowing people and feeling a kind of belonging and ownership in this community, not just Traverse City; but the region at-large. I feel invested in it. I belong to it.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place?

Yes.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

That’s really an imponderable. That opportunity to write that column — would that have happened if I was working at the Chicago Tribune? Maybe not. But because the Record-Eagle is a smaller paper and the town is a smaller place, that opportunity came to me. It was phenomenal. Would I have done the same work somewhere else? Maybe. I hope so. I think now I’d have the confidence to make that effort. I still think I’d be writing about the small things.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious writing practice?

I had an 11th grade English teach named Nelle Curry who was a writer and connected to the art world. She was a frumpy, dowdy woman with frizzy hair — you would never have thought of her as a glamorous artist; but she was a writer. She invited a group of six of us to join a creative writing group. We met at her apartment, which was a glamorous, high-ceilinged [place], with lots of books. She knew various visual artists. And, she was not married. She was a single, independent woman. It was an eye-opener for me. Her life was nothing like my mother’s. I loved considering Nelle Curry a free agent who was doing creative work and living in this book-lined apartment. I think that gave me another vision of possibilities for women. All the women I knew were just like my mom. They were home, raising kids, not working outside the home. Miss Curry gave me a glimpse of myself as a writer; but also a larger vision for women.

[NOTE: There is an essay about Miss Curry on P. 42 of Karen Anderson’s book Gradual Clearing.]

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Initially, a person who made an impact on me was Loren Eiseley. He’s really a science writer, wrote The Immense Journey, which is a collection of essays. He is such a beautiful writer. What I learned from him was the use of the extended metaphor. He would be writing about one thing but talking about a lot of other things. Sometimes people have talked about essays as a way to talk about big things and small things at the same time. Loren Eiseley taught me in The Immense Journey how to use an extended metaphor. You take a single experience, write about it accurately and then find meaning in it that can expand the significance of it. I admired that so. It seemed to me such a rich approach. He does it masterfully.

What is the role of publishing in your practice?

It was meaningful to me to have book of my radio essays published because radio is pretty ephemeral. With the Record-Eagle [essays], there’s a piece of newsprint if you want to save it. Radio comes and goes. It’s satisfying to have 120 essays between two covers instead of hoping someone might catch it on Friday mornings at 6:30 or 8:30. Publishing has given me an opportunity to reach a larger audience, and interact with that audience in ways that I don’t and can’t just by being on the radio.

Tell me about the feelings you have when you hear yourself on the radio.

Sometimes I sound better than other times. It’s always a little scary. What if it sounds terrible? But I listen because I learn. I should have read that sentence differently. I could have added more emphasis. Or: That part was good. I always listen with little fear, and a little hope.

Publishing one’s work is accepting that you’re going to be vulnerable. You’re putting yourself out there for any Tom, Dick or Harry to read. Does radio change that in any way? Or, exacerbate it?

It’s a risk. Being in any medium is a risk. Not everybody is going to like what you do for a variety of reasons. I guess you just have to learn to accept not everybody is going to love it. If possible, it’s great to engage with the people who don’t like what you’re doing, and have a conversation with them — if that’s possible. You can learn from people who don’t like what you’re doing. Sometime people will say, “Oh, why don’t you write an essay about X,” and it’s their particular passion. And I always have to gracefully say that the person who needs to write about X is YOU. You really care about it. I can only write about something I really care about. I suggest they do a letter to the editor, or a forum piece in the Record-Eagle. Get your concerns out there, they belong to you. I can’t do it as well as you can. I don’t have the passion for it, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I write about my everyday life so I keep living my everyday life; but I try to live it in such a way that I have a piece of my mind open to the possibility [of an event] being the focus of an essay. I think most artists are always scanning their experiences for the possibility of turning them into art. I certainly have that additional level of awareness, and discovery going on a lot of the time, whether I’m canoeing on the Manistee or shopping downtown or walking in my neighborhood. Or, remembering. People [ask her] how can I remember stuff that happened when you were a little kid? Well, you only need a fragment of that memory — the sound of a buckle boot — and you start to write about it, and it all starts unspooling from your memory. It’s all in there. You just have to invite it back. Memories are great. Reading books might stimulate something. Outdoor experiences. Relationships. All of that.

What drives your impulse to create?

Two things. I’ve mentioned one, and that is: It seems that I did come out of the womb in search of meaning. It was a joke in our family: Karen wants to know what it all means. There was a sense of searching for meaning, so I went to books and poetry; and an effort to extract meaning from my own experience, not just from the experts and existing authors. The second piece is I love language. I love it. I love the way it works, I love words, I love the way words fit together and create magical combinations that nurture our souls. Playing with language, finding the right word is a joy for me. And when I feel like I’ve nailed it … When I was able to say what just what I mean in the most beautiful language I could find inside of two minutes — that’s deeply satisfying. I really pay attention to language. Whether it’s people talking to me, or using it myself, or reading it in books. Our language is so rich and beautiful. Maxine Kumin the poet said all the good words have been taken, we can only rearrange them. Isn’t that wonderful? You don’t need new words. You just have to rearrange them so that it makes the world fresh.

Karen Anderson’s essays are heard Friday mornings, at 6:30 and 8:30, on Interlochen Public Radio. Read them here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Nancy McRay

Nancy McRay, 65, is “a fiber artist … mostly a weaver” of tapestries who pushes the medium out of its historic, domestic context, and into the Capital “A” Art world. She holds a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Michigan/Fiber Art; but getting there wasn’t a straight line in an academic system that lodged the fiber arts — weaving especially — in the home economics department. Nancy has worked as a studio artist and community arts organizer since 1994. This interview took place in March 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity. Nancy lives in Williamsburg.

Describe the medium in which you work.

The work I do is tapestry weaving or multi-harness weaving. [1] Tapestry is weft-faced weaving, which means you only see the weft. The warp is covered. The weft is discontinuous, which means that if the weft goes from one edge to the other edge throughout, it’s a striped rug. It’s not a tapestry.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

I almost feel like I wasn’t given a say in the matter. I’m mysteriously drawn to it. In fact, there have been times I’ve said to myself, I don’t care about fabric; what am I doing? And yet, every time I try to turn aside from weaving and try to pursue something else — like drawing or painting or sculpture — that’s fun, and I enjoy it; but it’s like, Now I have to get back to my work. I’m pulled back in. I don’t feel like myself unless I’ve woven that day.

It’s not just yarn. I enjoy knitting and crochet and even quilting and sewing; but that’s not my work. I used to own a yarn shop [2] so I would be seduced by soft yarns, textures, colors. My customers would be, as well. When I started a spinning group in my shop I … was bemused by their level of interest in the fiber. They were passionate about which sheep [wool the yarn was made from], the crimp, all of these technical terms. I understood; that’s how I feel about weaving. When I opened [Woven Art] I was intending to sell some yarn; but I was mostly intending to create a weaving center where I could have looms and teach people how to weave. Not everyone is as passionate about weaving as I am, so the direction of the shop became very supportive of knitters.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?