Creativity Q+A with Karen Anderson

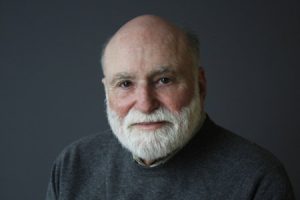

Karen Anderson came “out of the womb searching for meaning.” The Traverse City writer has found it in a bowl of oatmeal, buckle snow boots, canoeing the Manistee River, and the historic neighborhood in which she’s lived for several decades — among other places and things that, at first blush, seem mundane. But it is this very ordinariness about which she writes that has spoken, clearly and loudly, to readers of her newspaper column, and now to listeners of her weekly radio essays. Karen Anderson’s love affair with words and ideas has been part of the locality since the 1970s; and continues — in spite of a college professor’s lament that marriage, motherhood and all the rest might diminish her creativity. This interview took place in January 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work. What is your work?

Currently, my medium is radio, and I contribute weekly essays to Interlochen Public Radio.

How many books have you published and what are their titles, publication dates?

Three: Letters from Karen in 1978; A Common Journey in 1982; and Gradual Clearing: Weather Reports from the Heart in 2017.

How many essays have you written and read on IPR?

I started contributing a weekly essay in 2005. So, if you do the math, it’s weekly … 52 a year times 15 -16 years, whatever that is.

How long did you published essays in the Traverse City Record-Eagle?

It was a weekly column, and I did that for 30 years. I was invited to start writing a personal column in 1973, and continued until 2003. Then, Peter Payette [then News Director, now Executive Director] at Interlochen called me up and said, “Your columns could be adapted for radio. Would you be interested?” And by then, I really was interested in trying a different medium. I’d been doing the Record-Eagle for a long time. I really love IPR … I felt like this would be a new growth opportunity. And it was, and is.

What are the difference between writing for print and writing for radio?

I had to learn that, and thanks to Peter Payette, he could be my coach. When I wrote for the Record-Eagle, my columns were about 700-words-a-piece, and my essays for Interlochen are only 200 words. They slide them into a two-minute slot between news stories. That’s a big drop in words, so you have to condense dramatically. I learned a number of things. One is: You can really only include one idea per essay. You can’t really ramble around and add ideas and detours. There are no detours in two minutes. Another thing: Your sentences need to be short because people are listening. They don’t have text in front of them like when they’re reading the Record-Eagle. They’re listening. And if they miss something, or if your sentences are too complex, or your words are too big and unfamiliar, it’s going to go by them, and you can’t go back. Simplicity — both in terms of concept, and I don’t mean simplistic, [but sentences that are] straightforward, with focused ideas, short sentences, sentences that are clear, without lots of adjectives or dependent clauses. Here’s the thing I learned: I take out words; but I can add in with my voice what I take out in words. I can add inflections, and pauses, and emphasis that I can’t do in print. Even though it’s shorter, I really like being able to use my voice. It’s a way of indicating to the listener what I care about. With radio, there’s an intimacy about it. From time to time IPR gets people in from NPR to visit the station and coach the staff. I worked with a woman years ago … and she talked about how intimate radio is. It’s helpful if you think that you’re just talking to one person. You don’t imagine yourself talking to a thousand people. And, probably most people are listening alone. I like the immediacy and intimacy of radio, which is different than print.

IPR gets people in from NPR to visit the station and coach the staff. I worked with a woman years ago … and she talked about how intimate radio is. It’s helpful if you think that you’re just talking to one person. You don’t imagine yourself talking to a thousand people. And, probably most people are listening alone. I like the immediacy and intimacy of radio, which is different than print.

What draws you to writing, to the written word? Why did you choose writing as a vehicle of creative expression?

Because I learned early that I was good at it. I was an avid reader, and I started writing terrible, youthful things, essentially copying The Secret Garden as if it were my own novel when I was in the 6th grade. When I was in 10th grade, the assignment was to write a personal letter, and I wrote one that I made up. I made up a family in which I had an older brother who could fix me up on dates. The teacher gave an “A” on this and read it to the class. She liked it because it had so many personal details, and it was so conversational. She seemed to think I had a talent for writing, and I think that gave me some confidence and focus about going forward in that realm. I was also in art classes, and I had a small amount of talent in visual art; but it didn’t interest me as much as writing. I was hungry to ferret out the meaning of life, and I felt like words were my vehicle, metaphors and language always attracted me. That was the path I followed.

Did you receive any formal training in writing?

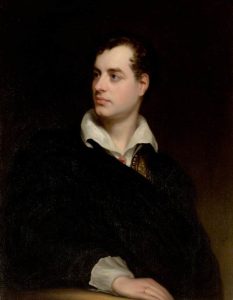

I majored in English literature at U of M, [Karen received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan in1966] wrote lots of papers, and went back and got a master’s degree in English literature [late 1960s]. That was some formal training. I had some really good coaching from one professor. We had to write a paper on Byron. I didn’t know anything about Byron, so I went and got a bunch of book about Byron from library. I wrote a paper quoting all the experts on Byron, and got a “C” on my paper, which shocked me. This is my major. So I went to see the professor, and he said, “I don’t want to read about what the experts think about Byron. I already know that. I want to read about what you think about Byron.” Oh my god. I didn’t have any thoughts about Byron, but he gave me permission to have ideas about something that he thought might be valuable. That was really important to me. Trust yourself.

How did your formal training affect your development as a writer?

It made me a good writer. Writing academic papers for high-quality professors is rigorous, and I learned how to express myself in a grammatically correct and beautiful way. I was taking a Chaucer class … We could write either a creative or research paper. Of course, I wanted to do a creative paper, so, I decided to make up an additional Canterbury Tale pilgrim. I made up my own pilgrim to add to the gang that was going to the cathedral. I wrote my paper in iambic pentameter rhymed couplets It was quite a few pages of single-spaced rhymed couplets, and I had so much fun doing it. My professor gave me an A+, which was thrilling. He said [I] seemed to have a gift for writing. Here’s the awful, additional thing he said. We’re talking about the 60s now. He said, “You seem to have a real gift for creative expression. I hope, when you get married and have children, it won’t dissipate your interest in intellectual pursuits,” or something like that.

How did that comment, in retrospect, influence how you went forward in the world with your writing?

Here’s the embarrassing thing: I was so thrilled that I got an A+, and that he said I was a really good writer, that I didn’t feel sufficiently offended by his additional comment that my path to motherhood and marriage would dissipate my intellectual pursuits. I never believed that; but I wasn’t as offended as I would have been after the Women’s Movement brought to my attention the ways in which the patriarchy has shaped our world. Consciousness raising was on the horizon; but it wasn’t there. I look back on it now, and I’m just appalled that he would even [say] that; and worse, that I didn’t object; but the other messages were valuable to me.

Beyond your formal training, what are the other ways you learned about your craft?

I attended the Bread Loaf Writers Conference in Vermont [1977-79, 1983 as a Bread Loaf Fellow] … It’s an extraordinary experience. It was two weeks of listening to top-notch writers read from their work, and then you attend workshops on craft, and then you can have your manuscript read by writers on staff, and meet with them to get feedback. All of those things were enormously helpful to me. It was nitty-gritty writing … I remember Hilma Wolitzer saying that her editor would go through her manuscripts and circle the words she’d repeated. That’s really good advice. Read your stuff out loud to yourself, and you’ll hear all the repetitions and the things that don’t make sense. I ended up going to Bread Loaf four times. One time, after I’d published a book of columns, I was there as a fellow, which meant I got to read from my own work, which was a great thrill. And, I got to go to Bloody Mary pre-lunch gatherings with the writers. I got as much help from those experiences at Bread Loaf as I did from U of M studying formal literature. It always helps to go to conferences and workshops where there are opportunities to get feedback on your work.

I had another good experience there, an ah-ha! moment. In my Record-Eagle columns I used to include a quote from a famous person at the beginning of the column, that was related to the topic. Writer Geoffrey Wolff was the staff person who reviewed my first book. He really liked my essays. He said, “These quotes you have at the beginning of each essay don’t add anything.” He said, “You’re hiding behind the quotes as if you needed an authority to prove your idea was valid. Your ideas are strong enough. You don’t need those quotes. They’re just a distraction.” I was scared to take them out, that my readers would protest. But I took them out and nobody even mentioned it.

Describe your studio/work space.

It’s nothing special. It’s my daughter [Sara’s] bedroom. When she left for college I grabbed her bedroom for my office. It’s just a bedroom with a twin bed, and the Cabbage Patch dolls are on the bed.

How does your studio/work space facilitate your work? Affect your work?

It just gives me privacy. A place where everything is available.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

I write about my own experiences. Daily life. Ordinary experiences. Also: nature — I write quite a lot about doing things outdoors. I write about relationships, and often a theme is the search for wisdom, or insight about the meaning of life. That sounds grandiose. Trying to extract meaning from my daily experience is the effort, the energy behind the essay.

You’re heard weekly on Interlochen Public Radio. Characterize these essays you write and read on air.

You’re heard weekly on Interlochen Public Radio. Characterize these essays you write and read on air.

They’re brief meditations on my experience and search for meaning. The subtitle of my book [Gradual Clearing], which was suggested to me by a writer friend, it’s Weather Reports From The Heart, which is a little corny; but does suggest what I’m after.

The Interlochen Radio essays are two minutes in length. What are the challenges to expression and writing posed by such a compact “space”? How do you craft an idea for such a compact space so that you can take the idea through its full arc?

Quickly. There’s one idea. Short sentences. Simple words. Focus. Focus. Plus, a kind of intimacy. That’s the construction of them. That content is, I’ve tried to be willing to be vulnerable, to be confused, to not have answers, to share from personal experiences in an honest way. Here’s the thing, and this is from the time I started writing columns in the Record-Eagle: When people talk to me about my columns, or now, my essays, they don’t talk about my experience, they talk about their experience. They’re really not interested in my experience except as it connects them to their own experience or insight or understanding. So, they come to me and tell me about themselves, which is wonderful. It’s like we’re more alike than we are different. And, people connect to what I write in ways I could have never predicted.

The confined spaces of your former column, and now, the radio essays, impose boundaries and limits on your writing. I wonder if these confines are humbling, if they remind the writer that every word isn’t precious?

I don’t think they’re humbling. I think they’re challenging. Another formal and informal training that was helpful to me is writing poetry. When my granddaughters were home schooled, I offered to teach the poetry curriculum. So, every week for seven years, they came to my house. I decided I should get more serious about writing poetry, and I took a class at the [Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City, Michigan] with [Leelanau County native] Holly Spaulding, and discovered how difficult poetry is to write. It’s even more distilled than my essays. It condenses things down even further at its best. That was really helpful. You find you can leave out a lot of words you thought you couldn’t leave out. It doesn’t take away, it adds to. You get right to the heart of things. I confess now that I’m very impatient with people who cannot be brief, either in writing or in speaking.

Are the essays you published in the Traverse City Record-Eagle different in any way than the ones you’re writing for and reading on the radio?

They were longer, so I had time to meander and include various additional thoughts and ideas. They weren’t as focused. When I started writing them, I was in my 20s. We’re talking not quite 50 years ago. I didn’t know nearly as much as I know now. Here’s the other thing: When I first started writing my column I was the “roving reporter.” I would write about fun activities around town, and then I might throw in one about my grandmother. The ones that people liked were about my grandmother. I learned from my audience that people really liked personal stories. My maturity level, my self-awareness, my repertoire of experiences were much less in the 70s than they are now. The goal is the same — to extract meaning from my experiences — but I think that I’m better at it because I know more about myself and about writing.

Who is your audience?

Right now, it’s the IPR listeners who are in Northern Michigan, and all over the place. When my book of essays was published in 2017, the audience expanded further. Not necessarily people who can hear me, or who have ever heard me, they discover my book … I really feel privileged, truly, honored and grateful to have a weekly audience. It’s a very precious thing.

What kinds of clues have you gotten along the way that tell you who your audience is?

I think it’s evenly men and women. I get letters, emails, comments out in the community. For example: When I was writing a weekly column in the Record-Eagle, my picture was in the paper every week, so people would recognize me when I was out around town. Now, people recognize my voice. It is the strangest thing. My husband and I were at a nursery buying a Maple sapling for the backyard, and the forester telling me about the tree said, “Oh, I know you. I listen to your essays on IPR.” He recognized my voice, which is fascinating when you think how distinctive our voices are. I have those experiences quite often … When I published my book and I went out and did readings — it was weekly, for a year I was out on the trail — there were as many men as women in the audience.

What do you do with the feedback you get from your readers and listeners?

I use it. Depending upon what it is. Knowing what they like is a good clue to themes and points of view resonate with people. If they don’t like it, I can use that, too — if I think it’s valid … I write a variety of essays. One recently was about oatmeal for breakfast. Now, that’s pretty mundane. Right? It wasn’t profound. I got more response to that oatmeal essay than I’ve had in quite a long time. People weighing in on how they like their oatmeal. It was humorous to me. I could never have predicted that, and I loved it. It’s a reminder that ordinary life that’s where we live, day-to-day, in our kitchens eating oatmeal. It reinforces my belief that ordinary experiences can connect us. And I just don’t mean describing oatmeal. Usually there’s some level of understanding or humor or insight about daily experiences. It delights me to find what people particularly enjoy because it isn’t often what I expect.

I use it. Depending upon what it is. Knowing what they like is a good clue to themes and points of view resonate with people. If they don’t like it, I can use that, too — if I think it’s valid … I write a variety of essays. One recently was about oatmeal for breakfast. Now, that’s pretty mundane. Right? It wasn’t profound. I got more response to that oatmeal essay than I’ve had in quite a long time. People weighing in on how they like their oatmeal. It was humorous to me. I could never have predicted that, and I loved it. It’s a reminder that ordinary life that’s where we live, day-to-day, in our kitchens eating oatmeal. It reinforces my belief that ordinary experiences can connect us. And I just don’t mean describing oatmeal. Usually there’s some level of understanding or humor or insight about daily experiences. It delights me to find what people particularly enjoy because it isn’t often what I expect.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

It depends on what I need, whether it’s the actual sentence construction or themes. I’ve always gotten good feedback from Peter Payette at IPR; from my poetry teacher Holly Spaulding, who helped me edit the essays in my most recent book. She’s absolutely relentless and fearless about taking things out. I always valued her feedback. [IPR Program Director] Dan Wanchura is the guy who produces my essays for IPR. I send him ideas before I write the essays, and he’s very honest about whether he thinks [an essay idea] has has legs, or not, or how it might grow legs. From time-to-time, I’ve had a writing group. I was in a writing group for a couple years with several really talented, regional/Northern Michigan writers, and they also helped me put my book together. I can still go to any one of them for counsel, if I need it.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

A whole bunch of things. Experiences. Overheard conversations. Sometimes a memory because I write about my childhood. I recently wrote about my brother getting to wear buckle boots when he was a little boy. I didn’t get buckle boots because I was a girl. I had to wear those dorky zip-up boots with fur around the top. It was partly a meditation: I’d perceived that things were already better for boys than girls. I had so many men telling me about their memories and experiences with buckle boots. Childhood is a rich source of memories and ideas. Books that I read, conversations I have, daily life, which keeps happening. Then I try, like many writers, to quick jot down the idea. I only need the idea. I get it on paper, in little notebook, and then I can revisit it when I have to write a batch. I write about 12 [IPR] essays at a time. And, then I go tape 12.

A whole bunch of things. Experiences. Overheard conversations. Sometimes a memory because I write about my childhood. I recently wrote about my brother getting to wear buckle boots when he was a little boy. I didn’t get buckle boots because I was a girl. I had to wear those dorky zip-up boots with fur around the top. It was partly a meditation: I’d perceived that things were already better for boys than girls. I had so many men telling me about their memories and experiences with buckle boots. Childhood is a rich source of memories and ideas. Books that I read, conversations I have, daily life, which keeps happening. Then I try, like many writers, to quick jot down the idea. I only need the idea. I get it on paper, in little notebook, and then I can revisit it when I have to write a batch. I write about 12 [IPR] essays at a time. And, then I go tape 12.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

Not much. I’ve been doing it so long. All I need is the idea. It’s like Hemingway saying begin by writing the truest sentence that you know. All I need is an image or a sentence and then it writes itself, not always well. I don’t want to know what the end is. I don’t know where I’m going to arrive because I trust the process to take me where it needs to go. If I already have an ending in mind, I often get derailed from it, and it isn’t as strong as letting the material go where it goes.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Yes. I might have several essays in various stages of development. Sometimes, I will start to write and find, for whatever reason, the stars are misaligned, and I cannot write a coherent sentence today. It just won’t happen, and I could sit here all day and it just wouldn’t change. So, I leave it, and then the stars realign, and the next day the sentences come to fruition. Sometimes I just have to leave a piece, or the idea, or I can’t figure out the ending, so I just have to leave things and revisit them, so I can work on other things while I’m waiting.

What’s your favorite tool?

I just write on a PC pretty much. Computer keyboard.

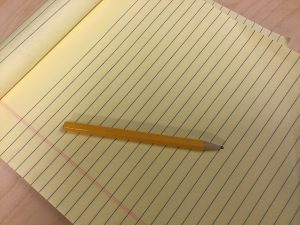

You didn’t come out of the womb writing on a computer keyboard, so talk a little bit the difference between writing by hand with a pencil and paper versus the word processor/laptop.

I used to write everything longhand on legal pads. But the computer arrived, and I was working full-time in public relations and marketing at Northwestern Michigan College. That was my full-time job, and I had to learn to use the computer for my job. I soon learned how much easier it was to revise things on my computer than it was any other way. My work forced me into using a computer.

I used to write everything longhand on legal pads. But the computer arrived, and I was working full-time in public relations and marketing at Northwestern Michigan College. That was my full-time job, and I had to learn to use the computer for my job. I soon learned how much easier it was to revise things on my computer than it was any other way. My work forced me into using a computer.

What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I make notes in a little notebook. And if I just have an idea for an essay, it’ll go into my notebook if I’m out and about. Or, I grab a scrap of paper, or a receipt from Meijer. It could vanish if I don’t write it down. My file of essay ideas is full of scraps of paper.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

When I went to work at the Record-Eagle in [the early] 1970s. It was just job, like a Gal Friday. I was reading proofs, and doing grunt work in the ad department. But I approached Bob Batdorff, who was the publisher then, and I said, “You don’t have any book reviews in the Record-Eagle, would you let me write some?” He told me to write a few and I did, and they liked them, and after they’d used a half dozen he said, “You’re a good writer, would you like to write a weekly column? Just your own. Whatever you want it to be.” It was an extraordinary invitation. At that moment, I began to think how I could shape something that was my own idea, that wasn’t about somebody else’s book or life. I started writing a weekly column for the Record-Eagle in 1973. That was the beginning of taking myself seriously as a practicing writer. And they paid me.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Not very much. My essays for Interlochen are part of their website. I have my own page where they archive my essays; but I don’t Twitter, and I don’t have my own website. I’ve thought about creating one, but I just haven’t done it.

What do you believe is the creative practitioner’s role in the world?

I think of Holly Spaulding when she was teaching us poetry, and she would say, “Make it fresh.” I think our responsibility is to take whatever ideas we have, and make them fresh so that someone looks at them anew, so that they a reason to pay attention … to any concern, insight, or wisdom we have to offer them. It depends on your purpose, if you’re trying to persuade people of something, or to enrich their daily lives. The other thing I’ve talked about before: Connecting with other people. Demonstrating how we’re all more alike than different. That we can bond over oatmeal. That there are commonalities in the human experience, which are really nourishing to consider and celebrate.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

My neighborhood: I live in Central Neighborhood in a 100-year-old house. I love this old neighborhood. I feel at home here. And, also, the larger outdoors — my husband and I go canoeing and camping and hiking in this region and beyond. Those things also really nourish me. That whole small town thing. Traverse City is a small town in some ways, and I like that.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s an accessible place. Even though we have a lot of new people moving in, I can still walk downtown and see people I know and chat with. I can talk with Jim Carruthers, the [former] mayor of Traverse City who bikes by my house. There’s still a sense, since I’ve lived here a long time [since 1984], of knowing people and feeling a kind of belonging and ownership in this community, not just Traverse City; but the region at-large. I feel invested in it. I belong to it.

Is the work you create a reflection of this place?

Yes.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

That’s really an imponderable. That opportunity to write that column — would that have happened if I was working at the Chicago Tribune? Maybe not. But because the Record-Eagle is a smaller paper and the town is a smaller place, that opportunity came to me. It was phenomenal. Would I have done the same work somewhere else? Maybe. I hope so. I think now I’d have the confidence to make that effort. I still think I’d be writing about the small things.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious writing practice?

I had an 11th grade English teach named Nelle Curry who was a writer and connected to the art world. She was a frumpy, dowdy woman with frizzy hair — you would never have thought of her as a glamorous artist; but she was a writer. She invited a group of six of us to join a creative writing group. We met at her apartment, which was a glamorous, high-ceilinged [place], with lots of books. She knew various visual artists. And, she was not married. She was a single, independent woman. It was an eye-opener for me. Her life was nothing like my mother’s. I loved considering Nelle Curry a free agent who was doing creative work and living in this book-lined apartment. I think that gave me another vision of possibilities for women. All the women I knew were just like my mom. They were home, raising kids, not working outside the home. Miss Curry gave me a glimpse of myself as a writer; but also a larger vision for women.

[NOTE: There is an essay about Miss Curry on P. 42 of Karen Anderson’s book Gradual Clearing.]

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Initially, a person who made an impact on me was Loren Eiseley. He’s really a science writer, wrote The Immense Journey, which is a collection of essays. He is such a beautiful writer. What I learned from him was the use of the extended metaphor. He would be writing about one thing but talking about a lot of other things. Sometimes people have talked about essays as a way to talk about big things and small things at the same time. Loren Eiseley taught me in The Immense Journey how to use an extended metaphor. You take a single experience, write about it accurately and then find meaning in it that can expand the significance of it. I admired that so. It seemed to me such a rich approach. He does it masterfully.

What is the role of publishing in your practice?

It was meaningful to me to have book of my radio essays published because radio is pretty ephemeral. With the Record-Eagle [essays], there’s a piece of newsprint if you want to save it. Radio comes and goes. It’s satisfying to have 120 essays between two covers instead of hoping someone might catch it on Friday mornings at 6:30 or 8:30. Publishing has given me an opportunity to reach a larger audience, and interact with that audience in ways that I don’t and can’t just by being on the radio.

Tell me about the feelings you have when you hear yourself on the radio.

Sometimes I sound better than other times. It’s always a little scary. What if it sounds terrible? But I listen because I learn. I should have read that sentence differently. I could have added more emphasis. Or: That part was good. I always listen with little fear, and a little hope.

Publishing one’s work is accepting that you’re going to be vulnerable. You’re putting yourself out there for any Tom, Dick or Harry to read. Does radio change that in any way? Or, exacerbate it?

It’s a risk. Being in any medium is a risk. Not everybody is going to like what you do for a variety of reasons. I guess you just have to learn to accept not everybody is going to love it. If possible, it’s great to engage with the people who don’t like what you’re doing, and have a conversation with them — if that’s possible. You can learn from people who don’t like what you’re doing. Sometime people will say, “Oh, why don’t you write an essay about X,” and it’s their particular passion. And I always have to gracefully say that the person who needs to write about X is YOU. You really care about it. I can only write about something I really care about. I suggest they do a letter to the editor, or a forum piece in the Record-Eagle. Get your concerns out there, they belong to you. I can’t do it as well as you can. I don’t have the passion for it, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I write about my everyday life so I keep living my everyday life; but I try to live it in such a way that I have a piece of my mind open to the possibility [of an event] being the focus of an essay. I think most artists are always scanning their experiences for the possibility of turning them into art. I certainly have that additional level of awareness, and discovery going on a lot of the time, whether I’m canoeing on the Manistee or shopping downtown or walking in my neighborhood. Or, remembering. People [ask her] how can I remember stuff that happened when you were a little kid? Well, you only need a fragment of that memory — the sound of a buckle boot — and you start to write about it, and it all starts unspooling from your memory. It’s all in there. You just have to invite it back. Memories are great. Reading books might stimulate something. Outdoor experiences. Relationships. All of that.

What drives your impulse to create?

Two things. I’ve mentioned one, and that is: It seems that I did come out of the womb in search of meaning. It was a joke in our family: Karen wants to know what it all means. There was a sense of searching for meaning, so I went to books and poetry; and an effort to extract meaning from my own experience, not just from the experts and existing authors. The second piece is I love language. I love it. I love the way it works, I love words, I love the way words fit together and create magical combinations that nurture our souls. Playing with language, finding the right word is a joy for me. And when I feel like I’ve nailed it … When I was able to say what just what I mean in the most beautiful language I could find inside of two minutes — that’s deeply satisfying. I really pay attention to language. Whether it’s people talking to me, or using it myself, or reading it in books. Our language is so rich and beautiful. Maxine Kumin the poet said all the good words have been taken, we can only rearrange them. Isn’t that wonderful? You don’t need new words. You just have to rearrange them so that it makes the world fresh.

Karen Anderson’s essays are heard Friday mornings, at 6:30 and 8:30, on Interlochen Public Radio. Read them here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.