Cherie Correll, a mixed media artist living in Benzie County, retired in 2010 after decades of teaching art in the public schools. She said she took “2 1/2 years [after retirement] to decompress and figure out my practice. It was going to a lot of different directions.” This interview took place in November 2020. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

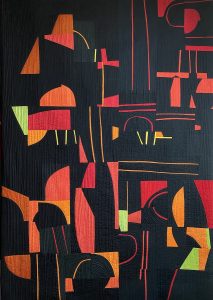

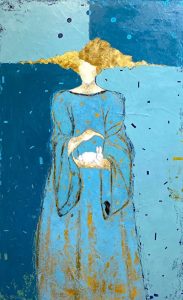

I work in a lot of mediums. If I had to narrow it down, I’d call it mixed media. I work in watercolor, acrylic, pastels, photography. I incorporate repurposed things and found objects. I’m not sticking to one media per se.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

Because it [mixed media] allows me to create in a broader sense. It gives me more tools to use. Sometimes the tools become a starting point. And sometimes they’re what I use to express what I’m trying to create.

Did you attend art school or receive any formal training in visual art?

I’ve been creating since I was a pre-schooler ….. I did go to college as an art major [Central Michigan University], and then transferred to Michigan State University for my last two years of undergrad, so my degree [BA] is from Michigan State. Many, many years later I went back and worked on a Masters at Central Michigan. And I’ve taken classes from Eastern, Western, workshops throughout the United States

You taught art in public schools.

I taught in various locations when we moved back from California. I did a lot of substituting and then was hired by Traverse City Public Schools ….. I ended up teaching for over 36 years in various schools. In fact, I’ve been to every school in Traverse City. I guess that’s my claim to fame as a teacher: I know every art room.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I think it was very important for me. I don’t know if it’s necessary to do strong work. I liked the idea of learning the elements and principles of design, the art history part of it was very important to me ….. I really enjoyed studying different indigenous people from throughout the world. I found that fascinating, whether it was African art, Asian art. In this part of the world, the Inuit world was interesting to me …… I shared that with my students and built a lot of curriculum around art history.

I think it enriches one when one learns how to mix colors, the color wheel, composition, how to study from real life. I found that was valuable in my practice.

Describe your studio/workspace. How does your studio/workspace facilitate your work? Affect your work?

It gives me space to explore different directions. I’m fortunate to have a heated section of our garage, that we partitioned off and drywalled. I kept the garage door so I can open up in the summer when the weather’s nice, and work flat or work out in the driveway and just bring it in. It’s really nice. I have a sink and windows. It’s full. It’s full of stuff. But I love it, and feel blessed to have that space; for years and years I didn’t, and I think it limited ….. my creativity, so now I’m like a kid set free.

If you were to guess, how many square feet is your studio?

It would be one section where you could drive a car into if you had a one-car garage. The problem is, it’s not a one-car garage. It happens to be bigger than our house. It’s a four-car garage. The far end of it is my husband’s tools and work area. And then the two middle sections are filled with bikes, snow blowers, that kind of things, but I’ve inched my way beyond our wall to our common space, and I often go into his work area to borrow tools and so forth. Funny. He built me shelving to put my canvases in, and that was very helpful.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

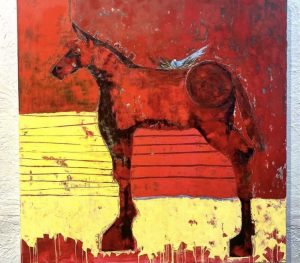

The overarching theme is our universe, the world, and how mankind and living things are influenced by the natural world, and how the natural world has influenced the human-made world .…. I’m drawn to found objects and re-purposing them ….. Oftentimes, I use things that have been discarded — plastic, tire parts — and I combine them with other things like tar and natural dyes.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

It comes from two different poles. It may be an idea I get from an actual physical object — something I’ve found or drawn to, I might see how that can develop into a sculpture or a relief or a mixed media piece.

I live with it for a while. I have quite a collection. The tire series I did came out of finding my first shred at the side of the road, and seeing what I could do with it, and then I spent many, many years incorporating tire part. I realized that they’re not something you just dispose of easily [from an ecological standpoint]. You can’t take them to recycle, and I kept accumulating them, so I wanted to find a way of using them and bringing another life to them.

The other side of the spectrum is an idea or thought that I want to convey brings me to how can I work with what I have in my head. It’s both the physical things that one can touch, and it’s also what comes from my brain.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

Sometimes I’m simply guided by an old piece that has not been resolved, and I want to put energy into resolving it, or else disposing of it. Sometimes disposing of it might mean tearing or spreading or whatever, and then I may find a use for parts of it in another piece. for example: in a collage.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

I work on several pieces at a time, and I do enjoy that, however, I have to limit myself to certain directions so I don’t get too spread thin. I need to follow through with a series before I open up another, completely different window. Sometimes I depart from that and go out and plein air paint .…. It is [a break]. I love the fact I can get out in nature and the elements. It’s uplifting and it’s also very challenging. I’m more an abstract artist rather than a representational artist, so it becomes a challenge to limit what one sees that we want to put down on a flat surface .…. It’s a good discipline. We’re not trying to create a realistic thing that becomes like a photograph, or else, why do it? ..… As far as I’m concerned, the artist needs to put their own eyes on what they’re doing and seeing.

Do you work in a series?

II like working in a series. If I find a direction that really excites me, I need to grow with that, and to take it farther. More recently, in the past year or two, global issues have weighed heavily on my heart, and I haven’t spent a lot of time doing plein air or getting sidetracked although I have a lot of things that are waiting to be resolved. I feel right now I have to explore what is weighing heavy on my heart. It may not be as uplifting as a beautiful scene or a sketching in my sketchbook a still life, I feel like time is of the essence, and it maybe I have a heightened awareness about our world. It may be because I’m getting older and realizing we’re only given so much time on this earth, and how am I going to make it most valuable .…. to me.

What’s your favorite tool?

This probably sounds selfish, but it’s my imagination. And the world around me.

What role does a sketchbook play in your practice?

I think it’s very helpful. I do more journaling that I do sketching. It’s a great discipline for one today a daily sketchbook. I found that my journaling has been beneficial because ideas go down in my journal, anything I’ve read that I find motivational or powerful, I write it down. It might have come from my upbringing; my dad wrote a page in his diary all his life since he was a youngster. Every day. Just a few sentences.

Sometimes it’s very hard and I don’t want to put any preconceived idea into the viewer’s mind, so [the title becomes] a broad word, or Number 1 or Number 2 or Number 3 in that series. When I do have to put a title to it, sometimes it just pops up. Other times, I’ll ask my husband, however, any title he comes up with is what he sees in it: “Oh. I see a specific thing” or “I see a creature”; that’s how he sees a title. I think it’s kind of interesting, but I do throw things back at him ……

I’m working on a series right now where I’m working in three-dimension — they’re sculptures. The first one I did over a year ago I call Balancing Act. It’s a metaphor for how I was feeling, and how life is. It’s a balancing act of life. That piece is completed.

I also bounce things off my daughter. She’s a visual and performing artist. We share, and it’s nice to have her as a resource. She’s very knowledgeable about what’s happening all over the world because she’s lived in Europe, Los Angeles, New York, and she has a lot of background.

What’s the job of a title?

It might help to give the viewer a better understanding of what the artist might be trying to portray.

When did you commit to working with serious [professional] intent? What were the circumstances?

I’ve always been serious about my practice. My art teacher in grade school was a driving force in getting me a one-person show at the Carnegie library [1] when I was in 7th grade. And, I had a show at the local camera shop when I was a teenager. I’ve always been serious about my work, but life goes on. And even though I was an art major, [some] things sometimes got in the way of being a full-time art practice: a mom, a wife, I had my teaching commitments, and most of my energy was for my students.

What role does social media play in your practice?

It connects me with other artists. I have a daily newsletter that I get [Art Daily] which I find very valuable in keeping me abreast of what’s happening in other parts of the world; what artists are doing, whose curating shows, what’s happening with art auction houses.

Do you use Facebook, Twitter, Instagram?

I am on Facebook. I don’t post a whole lot, but I love the people who are posting their work. It’s a social connection and I can see what they’re working on and how they’re growing. It’s really nice, however, I’m not one to do it myself unless there’s some huge show that’s coming up. I just don’t do that. It’s distracting me. You can really get sidetracked. I’m not a very good promoter but I love looking at other people’s work. Especially when I know them. Everyone says Instagram is great for artists .…. I just haven’t explored any of that.

What do you believe is the visual artist ’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

I think it’s being true to themselves. Being honest, and doing the work, and growing and finding their own voice.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It can’t help but influence someone’s work when we’re so blessed ..… to live with nature all around us. The seasons — we’re fortunate to have the season. We’re fortunate to be surrounded by water and all the elements. It can’t help but influence one’s work. I live at the corner of Benzie, Leelanau, and Grand Traverse counties — three of the most beautiful places in the world. It the most beautiful place, and I wouldn’t want to be in any other place. However, social media, bring out of my little cubbyhole here and gives me exposure to other places in the world.

How long have you lived in Northern Michigan?

I was born in TC, and I moved away when my husband and I were first married, and we lived in Northern California for three-and-a-half years [moved back in 1972].

Is the work you do a reflection of this place?

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

I think I would be doing different work. If I had a huge studio in a big city, I think my work might be totally different because I’d be surrounded by a different kind of energy. And a different kind of influence: the sounds, the smells, all the senses, would take on a different meaning.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

I knew a few. One of my parents’ dear friends was an illustrator, and she worked for Hallmark. And, she had a very creative mind. Her name was Mary Dorman [2], and she invented the pop-up card. She was the first to make pop-up cards for Hallmark. She would write little booklets, a lot of humorous things about simple things in life ….. My first impression was “what a wonderful job.” And then she came and spoke at one of my high school career days, and she was very discouraging about the profession. I know it’s a lonely profession. You’re working at your own drawing board. My heart sunk to my stomach. I don’t know how much she really enjoyed it.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Oh, there have been so many, from the cave paintings of our early ancestors, indigenous people throughout the world, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, the Impressionists for light and color. As a young artist, I was drawn to the Abstract Expressionists, especially Mark Rothko and Helen Frankenthaler. I learn from many art instructors and other working artists around the world. We have such a strong artist’s community right here in Northern Michigan, too.

But to answer your question with a specific person I would have to say my mother has had the most lasting influence on my work and art practice. She provided me an environment as a child and during my growing up years to express myself through art, and she showed me through her example that it also takes discipline. She was an artist in different ways — with her skills in cooking, gardening, dressing, decorating, and her whole personality.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

I’ve been involved in various critique groups. We all work in different media, and we all have different styles and kinds of practices. I find that’s very valuable to share with people you respect that might not necessarily be working in the same direction. We all learn from each other. Art friends that I highly respect, and they’re sure are enough of them around here.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

I think it’s healthy. It takes a lot of bravery for anyone, no matter how long you’ve been a working artist, to take that leap and put your work out there. For some, it’s an economic necessity. They’re building a business. I would have loved to have primarily been a working artist and not an educator, but that’s really risky. I found the needs of my family required me to go back to teaching, although I took a break and had my freelance design business [painting, furniture restoration] ….. to have the security of a teaching career, and have insurance, for one thing, led me to do that …..

Why do you take the risk to put your work out there? What does that do for your practice?

I think it can be very helpful. For example, It’s not going to deter me from my main direction, but I love a theme for a show. It gets people out of their heads .…. and I think how can I make that theme work for my own practice? And be true to what I’m doing? That becomes a really nice challenge ..… It’s a departure point …… It gets you out thinking beyond your own little vision. It’s stimulating, is what it is. It’s very motivating. And to be disciplined with a time stipulation is another thing.

Footnotes

1: The Traverse City Carnegie Library is located at 322 Sixth Street. It is now the Traverse City location of the Crooked Tree Arts Center.

2: Mary Dorman Lardie [1913 – 2009] lived on the Old Mission Peninsula. She was hired in 1933 as the first editorial staff member of the Hall Brother greeting card company, which later became Hallmark Cards.

Top Image: Cherie Correll at the door of her studio.

Learn more about Cherie Correll here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber + collage.