Blacksmith Scott Lankton [left] was “hooked on hot steel” the first time he worked with it. The Leelanau County artist, 66, went on to find a vocation in the forge, pounding metal into domestic objects of great beauty. Scott Lankton also found that this old art + craft form can be put to use in the pursuit of peace, and be a way of raising awareness about gun violence — as he raises the profile of his calling, who is a blacksmith, and how it is more than an historical craft form demonstrated in museum settings. This interview was conducted in July 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

I work iron and steel, but I’ve also worked in copper and bronze, in silver and gold, most metals really, but iron and steel my favorites. I’m a blacksmith. I do custom metalworking.

What draws you to blacksmithing and working with metal?

I started out in jewelry, working in gold and silver, but when I saw some guys working with hot steel, I was hooked. They let me try it, and I was hooked for life.

What was it about the hot steel that hooked you?

It was the spontaneity. The fact you have to think ahead and work quickly, literally strike while the iron is hot. You have to have a plan in mind, but you also have to adapt quickly to changing circumstances.

Did you receive any formal training?

I got a BFA from Western Michigan University in jewelry and metalsmithing [1978].

Did you have any coursework in blacksmithing?

I was studying small metals — the tiny, shiny things, like gold or silver. But I started working in copper, making vessels, raised hollowware. And, some other students had a forge set up in one of the garages at one of the university buildings. I though it looked neat, that I could make bigger things. My teacher, [the late] Professor Bob Engstrom, encouraged me.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I think that it did. There are many blacksmiths who’ve had a university education, and higher education, but many haven’t. Having an experience in art school taught me how to draw, it taught me how to see things better, how to think about art, doing critiques.

Describe your studio space.

My studio [Sleeping Bear Forge], which is my fourth studio, is big, well lit, well equipped, and lets me do just about anything I want to do with metal working. I wish I’d had it earlier in my career. It would have facilitated me to do more work. It’s warm in the winter, and many studios were not. For many years, it was either you work or you freeze.

My studio [Sleeping Bear Forge], which is my fourth studio, is big, well lit, well equipped, and lets me do just about anything I want to do with metal working. I wish I’d had it earlier in my career. It would have facilitated me to do more work. It’s warm in the winter, and many studios were not. For many years, it was either you work or you freeze.

What themes and ideas are the focus of your work?

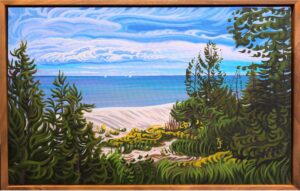

Nature, by far, is really the biggest influence. I’ve always liked nature: the animals, the trees, the birds, the lake shore here is pretty inspirational because of its vastness. Nature has been the biggest thing to inspire and motivate me to make things. So much art is an imitation of nature. I’m no different.

You moved your life, and yourself, and your family to Northern Michigan from Ann Arbor.

It started in 2016. I bought property [in Leelanau County]. And built the studio first, and then the house.

Ann Arbor is a different place than Northern Michigan. It’s called the City of Trees, and in that respect, nature is a big part of living in Ann Arbor. But you said nature is the biggest influence in your creative life. So, how did working downstate differ from working in Northern Michigan?

Ann Arbor may be the City of Trees, but still a rat race. It’s a great town. I lived in the country a little ways out of town, so I was still living in nature even though I was near the city. But the whole feeling you have when you live in a place full of cars, rushing around, doing their business, it’s a completely different thing than living in a place where people are not rushing around, where nature is far more dominant than commerce. It’s a much more relaxed, and contemplative environment to work in.

What prompts the beginning of a project?

An idea is like a spark. You have to act right away, or it may go out. If you want to build that spark into a fire you have to do something with it. Sometimes I don’t have an idea, but I’ll simply light a fire, start working on something, and ideas comes from the work itself. The process itself is full of ideas. The fire and the anvil and the hammer have been some of my greatest teachers. Just the experience of doing it.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project?

That really depends. If I’m just making a small thing, very little. If I’m making something functional, like a hook for the wall, there really isn’t much planning. I might do a quick sketch in chalk on the table. I’ve done a lot of large architectural work. [For these projects] there are meetings, and discussions, and drawings, and renderings depending on the needs of the client to understand it. Truly, blacksmiths often do something called sketching in iron where you actually make a small piece, which will answer many of the questions. If a photograph or drawing is worth a thousand words, the object is worth a thousand pictures. So to actually put something in someone’s hand, and let them touch it and feel it and see it, and see what the colors are, it’s a completely different thing. I do some sketching, not much. I do it as necessary to communicate with the customer.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

I usually have many projects going and underway, but I find that I work best, and can only really concentrate well, on one thing at a time. So, once a project has begun, that project will be worked on to completion — unless something else takes priority.

Do you work in a series?

Not usually. Most works are one-of-a-kind. A lot of my work has been functional in nature, stair railing and things like that. So, each one of those is unique, and it’s kind of a promise to the customer that we’re not repeating this design. This is your design. This is your piece. It’s not that we wouldn’t make anything that’s related or similar because I can’t help that. It’s still coming from the same source.

What’s your favorite tool?

A 1,000 gram hammer. It’s about 1.2 pounds, a typical cross pein, blacksmith forging hammer. I think it’s Swedish pattern. It’s a hammer I’m comfortable with. It’s a hammer I’ve done the majority of my work with. Blacksmiths have a lot of hammers. We have hammers like Imelda Marcos had shoes. We like to have hammers, but you’ll find one or two, or five or six are the favorites. Of those, I can usually pick one that would be the go-to hammer for most work.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

Not really. It’s a great idea, and I wish I did sketch and draw more. It’s a a wonderful way to have ideas. Usually there’s not a shortage of ideas.

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

The satisfaction. I feel best when I’m making something. I’m sure it’s tied up with a lot of things: work ethic, creativity, it’s pleasurable to see that I can make things. I feel best when I’m doing something, and that doing something is often making something.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life?

It really does [remain valuable]. The satisfaction of working with one’s hands — it’s very much in concert with working with one’s brain. There’s a lot of high, mental functioning going on. There’s tremendous satisfaction for anyone doing anything with their hands. Whether it’s cooking or painting, humans are innately geared to [work with their hands]. An awful lot of people do wonderful, valuable important work in our society today, but there’s not much to show for it. There’s not much to see. It disappears down a memory hole, it goes into a computer, into a file, and they don’t get to see what they made. It’s not easy to show people what they made. With an artist, at the end of the day, whether it’s good or bad, you literally get to see the fruits of your labor. And, that’s a valuable thing. The satisfaction of knowing I did something today, and I know what it looks like, that’s valuable. People miss that often in life.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

I started doing metalworking. I was lucky enough to get a job when I was 14 working at [Hodges Jewelry Store in Carrollton, Kentucky]. The people at this jewelry store taught me to size gold rings, to do engraving, to make things with my hands. When I was a kid, I was artistic. I was into drawing, sketching, and painting. I’d paint the horse. I’d paint the cat. The metalworking, the physicality of that, the direct working in the materials was attractive. I didn’t think about it too much. I went to college. I was going to study engineering like my father and my brothers. I went through a year of engineering school and said, “I don’t like this.” So, I started taking art classes. I transferred schools, to a school [from Ohio State University to Western Michigan University in 1974, graduating from [WMU with a BFA in 1978] where they had an a better art program, and got a degree in art: metalsmithing and jewelry. That’s where the blacksmithing came.

At that point, I was pretty much committed. This is what I’m going to do for a living. How I was going to do that, I didn’t know. Saying you’re going to do something can cause it to happen. Saying I’m going to move up north caused it to happen. I didn’t have a great plan for a career as a blacksmith. I didn’t know what it was going to be. What I tell [blacksmiths] starting out is: You make a piece, and you sell it. Then you make another piece and you sell that. And, you make another piece and you sell it. You just keep going like that. If you were to write a book about how to do this, it would be a blank book, and on the first page it would say, “Do the next thing.” Whatever that would be. By making a statement [I’m going to be a blacksmith], you can become a blacksmith.

It’s the build-it-and-they-will-come approach.

What I made changed a lot. Out of college, I bought an old blacksmith’s shop [in Hart, Michigan, 1979] that had done repair work. That’s what people came to the shop for, so I learned to do electric welding, and arc welding, and things I was not trained for in art school. I learned about making knives [by visiting an exhibition at Cranbrook Museum]. So, I saw [examples of] “art” knives, very fancy, jewelry-like knives, and I got interested in this. My professor Robert Engstrom encouraged me to do it.

There wasn’t an a-ha moment. I got a degree. I was making things. I started selling a few things. I did art fairs. I saw that I could make things, and people would buy them, and I could buy food. It was a simplistic progression. There wasn’t an inspirational moment. By deciding at a young age that I was going to do this for a career it made it happen. It was an evolution into: What can I do to put food on the table? Some of it was practical. And: What can I do to please myself aesthetically at the same time?

What role does social media play in your practice?

It does. For better or worse, and I have very mixed feelings about social media because of the way it has influenced our elections. But it does a lot of other things that are good. So, I still use Facebook. It lets me communicate with my colleagues around the country, around the world — there’s a worldwide and nationwide community of blacksmiths and blacksmiths’ organizations. And, we share information. Social media allows me to see the work other people are doing, how they’re doing it. Obviously, there was nothing like this 30 or 40 years ago, when I first got started. We had one or two books on blacksmithing. Now, there are dozens and dozens of fantastic, inspirational books. With social media and YouTube, there are videos on how to do almost anything. We were sort of lost [in the pre-social media days].

There was a renaissance in the American blacksmithing movement that started more than 40 years ago. An organization was formed called ABANA [Artist-Blacksmith’s Association of North America.] These 20 guys got together in Lumpkin, Georgia, and they formed this association, and they started having meetings, and conferences. I started going to these things in the early 1980s. There were hundreds if not thousands of blacksmiths there. There were Germans, and Swiss, and French guys doing this much more artistic blacksmithing than American colonial smithing. Social media has allowed us to share. The Forging For Peace Project we’re doing has been promoted well on social media. We that to show others what we’re doing, and get them interested. As a communication device, it’s really great. It is somewhat like trying to get a drink of water at Niagara Falls.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

I think artists, to a large extent, have always reflected aspects of society they feel are important. They’re holding up a mirror, in many cases, to social issues, to beauty issues, to aesthetics. Often, art is disturbing or controversial. Some of it’s hated at first, then accepted decades later. The role of the artist is to comment, and say something about society, and say it in a way that is not just with words.

Talk about the Forging For Peace Project in the context of this question.

Forging For Peace is an international project. It was initiated by a friend and colleague of mine, Alfred Bullerman, in Germany. He started Forging For Peace in 2015. It was in response to his friend’s workshop in Ukraine being destroyed in the first Russian invasion [in 2014]. We’re forging large nails because nails are a symbol of connection — among blacksmiths, and in general. We don’t think we’re going to stop a war by making big nails, but what we’re trying to do is get people to raise their awareness to think about why we have such a violent world, a violent country in the United States, why we have wars still. For smart people, we seem to be living in a very dumb way. And, I’m not sure why that is. We could do much better. Some of that is starting a conversation with people about why this is happening? And, what we could do about it? How could we slowly change this, and evolve into a more peaceful planet? I’m not thinking this is an easy thing, but I am thinking it’s a possible thing. I think it could happen if enough people get connected. Most people would like to live in peace, to live without the fear of getting shot going to the grocery store. It’s absurd we can’t find the political will to do something about that — as a community, as a country, as a world.

Forging For Peace is the latest, but not the first [peace project in which Scott has been involved]. In 1999, I got involved with an apprentice of mine, and we smashed guns. This was before Columbine. We were trying to get a conversation started about gun responsibility. About keeping guns away from children. It has been a long-term interest of mine.

Forging For Peace is mostly what I’m doing with my forging now. Making more things for people’s houses is not so interesting to me anymore. I’ve done it for 40 years, and this is a project worth working on. I’m devoting my time and resources to Forging For Peace, to help victims of war. But more than that, to start a conversation where we end up where there are no more victims of war because we have no more war. That’s a tall order, but we have to start somewhere.

The nails are a way to start the conversation. We’re doing these demonstrations because it’s interesting. People like to see blacksmiths hitting hot metal, and that draws them in. And, once they’re there, we say, “Well, I like peace. How ‘bout you?” Most people would agree with that.

You have some feelings about how blacksmiths are perceived, and the role of blacksmiths in the present day. Discuss.

There’s this stereotypical image of blacksmiths as big, always male, burly. They’re practicing this art, but everyone thinks it’s a dying art. In fact, there’s a huge, blacksmithing renaissance happening around the world now. A lot of blacksmiths now are women. It’s not unusual. Now it’s common as can be. And, historically, there are many women smiths in history. But we have this American idea that they’re horse-shoeing, knife-making brutes. Some blacksmiths would like to think of themselves as artists, and they’re reaching for the highest aesthetic expression as any other medium. It’s a very modern thing. Sure. We all use fire and hammers, but we use lasers and computers and CNC Machining. Blacksmiths have always embraced technology as it came out. Immediately. They do a hard job, and anything that makes it a little easier is usually welcomed.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

No. Not until I was an adult did I start looking around and [registering] that there are artists, and they make stuff. I was fortunate when I was a kid. I went to Italy, and saw the works of Michelangelo, DaVinci, Caravaggio, all these fantastic Renaissance artists. So, I was aware of art, but those weren’t people I knew personally. Working at the jewelry store taught me something. It wasn’t about art, but it was about craftsmanship, and quality, and doing quality work. That has always been my goal. I never thought I would be the best blacksmith, but I would be the best that I could be. And that has worked. To always do your best work is a good road to success.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

There were two people: Professor Robert Engstrom from Kalamazoo. He taught me a lot about doing good work. He taught me a lot about aesthetics. He showed me joie de vivre — how to love life and enjoy it. Bob was a World War II vet. He was a prisoner war, and they just about starved him. And, he loved food, and good living. So, we’d sit around, and have a glass of wine, and open up the safe and get out the rubies: Do you think this wine is more the color the Ceylonese rubies or the Burmese rubies?

The other major influence was Manfred Bredohl. Manfred is a German blacksmith, and a diploma’d designer — working more with pen, pencil, paper, and drawing, and very interested in modern design and aesthetics. He use traditional blacksmithing techniques to do things in a very untraditional design way. I worked with Manfred for four months in Germany [1985] but he [opened up] this European opportunity [to artists internationally] at his workshop in Aachen, Germany. He allowed us to work in the shop. We stayed in an apartment next door. Learned an awful lot about the blacksmith business — how much of that is in the office, how much of that is with the clients, and how much of it is in the work itself.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My peers. It would mostly be on the internet today. If you really want honest feedback, you have to ask for honest feedback, otherwise people will say something nice if they like it; they might not say anything at all if they don’t like it. Honest feedback would always come from my blacksmithing colleagues and peers.

How do you feed and nurture your creativity?

It’s pretty easy. Just living here. That was the overall, easy way to influence my work: move to a new place, to live in a new way. I didn’t intend to retire when I moved up here. I thought I would keep plugging away doing [architectural commissions]. What I found, taking time off to do that and build my home, it allowed me the space to breathe to think about what I wanted to do. A certain amount of that is simply walking on the beach, or walking in the woods, or hanging out with my partner, Karel. Doing these things is inspirational. And, if it doesn’t inspire me to make new work, it’s good enough all by itself.

What drives your impulse to make?

It’s a good question. Part of it is the selfish, good feeling I get from making things. It’s the stimulation, what it does for my brain, mind, body. My body feels better when I’m moving, and working. When I’m active. You get that endorphin rush working physically the same way runner, bicyclists, and other athletes do. The mind and the body are inseparable. What affects one, affects the other. Having my body do things physically affects my mind, and makes it feel better. It just really feels great to make things.

The satisfaction of seeing what you’ve done in a day — whether it’s good or bad, sometimes it’s a failure, but you learn from the failures. I don’t try to do things the right way first. I just make an attempt at it, and I learn something from it, from the process. From the process shows me a better way that I might do what I want, then I modify it, and do it again. That’s critical. The working itself is the fun, is the therapy. The object you produce in the end — OK: that’s the proof of that.

Read more about Scott Lankton here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.