Benzie County artist Jessica Kovan’s mixed media work is now on display in the GAAC’s Lobby Gallery. The Birds Are Watching, Kovan said, “asks viewers to pay attention from the vantage point of local bird species.” Kovan combines the personal with the political in this series of mixed media, avian vignettes created on cardboard. She took on the subject of local birds “in hopes of establishing a sense of interconnectedness between all beings.”

Category: Creativity Q+A

Creativity Q+A with Meg Staley

There has never been a straight line through Meg Staley’s career. But every experience — from sale clerk, to department store clothing buyer, to printmaker — has factored into the creative work she now does. The Leelanau County artist hand builds women’s clothing. Each piece is a composition that allows Meg, 70, to bring to it the myriad surface design techniques that make up her distinctive visual vocabulary. This is not, however, a story about fashion, but a life-long journey that uses clothing as an expressive tool. This interview took place in April 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

Several. Textile, printmaking, surface design 2 + 3 D, and clothing design.

You don’t work in a single medium. Talk about how all the things that comprise your practice, and how they draw you into them.

I don’t know what a “normal artist” is. And, I’ve never thought of myself as an artist. Period. I would say, in terms of the visual, it’s the texture, and color, and pattern that my mixture of media makes me happy. As far as motivation, it’s practical: It was money. A way in which I could express myself that was in service of women.

How was your work “in service of women”? How did you serve women through your clothing?

Because my early work was in building clothing for women — myself, and then for others. It’s been a life-long journey. I was always, from an early age, very, very excited by clothing. And I could easily wear clothing, and found myself making it for myself. Then, as I went on, I realized women — in general — would ask me style questions. And, through my first career at Nordstrom, I was a salesperson, and I went into fitting rooms with women, helping them find something they’re happy in. I realized women have all sorts of stories about their bodies, and what they don’t like. I got good at helping women find things that made them feel pretty. I was lucky enough, in my 20s, to put together a number of different jobs, in different places, in different aspects, to begin to understand that I could do something with that skill. When I got to a point where I could apply some of my skill set in terms of sewing, and making, and building, and printmaking, and all these other aspects of what I’d learned into designing for women, I understood that I had a mission.

You said you never thought of yourself as “an artist.” Talk about that.

My older sister showed a very early talent for representational art. She could draw a picture, and it looked like the thing. And, then she studied art. That was my interpretation of what an artist was. So, my sister was the artist in the family, and you know [siblings] can’t have the same roles. Even with a sewing machine, and sewing lessons, I was the only person who had ever sewed. I learned to sew, but in those days [in the 1950s and 1960s], that was not art. That was a craft that women did. So I didn’t ever associate it with art. That was my early story I told myself about not being an artist.

Was an “artist” something you wanted to be?

I wanted to be anything my sister was. In fact, telling on myself, there was this women who lived across the street from us in Bellevue, Washington, who was a cartoonist. I copied some cartoons and took the sketches over to her, and told her I’d sketched them. She told my parents she thought I was very talented. That’s part of my story, wanting to be something that I’m not, and not being happy with who I am.

Have you achieved the level of “artist”? Have you been admitted to the club yet?

Yes — because my definition has changed. Anybody who thinks a thought, sings a song, writes a sentence is an artist. I think of myself as a creative, sentient being. If you want to call that an “artist,” great, I’ll take it.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

That wasn’t until I was lucky enough to go to Smith College, which had a great art department. I learned there that art history was something — I never knew that was a thing. I took music history. I took music composition. I found out that all these things I was interested in were things [one could] study. Also, I took a drawing class in sophomore year — when I found all the things I thought I was supposed to study required so much reading, and I was not a fast reader. I thought I needed something I could do besides read. I had this wonderful [drawing] teacher. He was practitioner, and worked for Hallmark Cards. He was not considered a Ph.D guy — he was a practitioner. He taught me how to see differently. The following year, I took a composition course from him. He told me I had a great eye, and he thought I should pursue an art major. He was a major influence. And, he’d come from a very different background: He was not a fine artist. He was a commercial artist. He gave me a stamp of approval about the way I look at the world. I studied mostly photography and serigraphy [screen printing]. By the time I graduated [in 1973] I was a printmaker.

You use silkscreen printing in your business, Meg Staley Handmade.

During my business of 30 years, we did a ton of silk-screening on fabrics, and I collected more than 500 images that I still have. I have this library of single-color images. I could easily make new images, but I have such an amazing library that I use my favorites over and over again on fabric. I cut up the printed fabric, and utilize it on different places on a garment.

I began collaborating and making things [with her husband, Jerry Gretzinger] in 1985 [as Staley Gretzinger Inc.]. We sold the business [in 2008], and I had to come up with a different name for myself. I wanted and needed to continue practicing. I needed to make money, so I started a new label: Meg Staley Handmade. It started out being women’s clothing, and branched out to many things — home goods, soft bedding, quilts, patchwork pillows. That has grown into a lot of commission work for people who have lost loved ones. [She makes] legacy quilts, keepsakes — that’s very important work for me now. I get to work with an individual, and process with them their loss, and work with them to make something that has meaning for them. But I still make women’s clothing because it’s fun.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

When I went to Smith and began to study art, I was very influenced by my peers and classmates. I watched their process. I watched them not give up. I watched them come at a problem from a different angle. I watched them permutate their work in several different direction, and realized there’s no one way to make art. I never thought I’d make a career or a profession of it. I always thought it would be relegated to something that maybe I’d be lucky enough to play around with at some point. Serigraphy requires space. And it requires equipment. All art[making] has certain requirements, but this thing that I loved had a high threshold for practicing. I thought this was something I was going to have to say goodbye to. Thirteen years [after graduating] I started silkscreening again.

Describe your studio/work space.

It’s very me. If color is my religion, then my studio is my chapel. My studio is four miles away [from her home] in Cedar, Michigan. It’s an old general store built in 1909. It still has all its original floor, ceiling, and the original store front windows. It’s right on the main street of Cedar, two door down from the Cedar Tavern, and across the street from Blue Moon Ice Cream. When I try to describe where I am to the locals, those are the two reference points I use. The workable space is probably1,000 square feet, and then I have a whole basement.

The studio is so many things to me. It’s a place I can be by myself with my own music, puttering without any destination in mind. It’s sanctuary that way, and a celebration. In the middle of winter in Northern Michigan, and we’re all cooped up in our homes, it’s a place for me to go that’s filled with color and memories, and objects, and things hanging, and all of my favorite toys. It’s such a luxury for me. It’s the first space I’ve ever had that was really designed for me. We put in a big slop sink, and a big commercial dryer for setting inks, and a washing machine. I have tons of table space, tons of storage. Every other space I’ve worked in has been carved out of something more important. Or, it has been a living space, and I convert the dining room table into a print table, and then back again and put it all away. This has been a huge acknowledgment for me that I’m worth it. It also makes me incredibly happy.

Your studio is on the main drag in Cedar. What’s your relationship with the public walking by?

Initially I thought I could do a little store here. And, I quickly remembered my frustration and impatience being at Nordstrom, having people walk in the midst of me making an incredible display, interrupting my artist process, and wanting me to help them. I don’t need to do retail anymore, and I don’t want to. I have one [Leelanau County] store that carries my work [Ruth Conklin Gallery], so I can tell people who want to buy my work to go to that store.

One of the things about having this space is that there are no barriers/excuses for getting work done. I don’t have to reset it up. I don’t have to do a whole lot to get myself ready to work. I can just walk in there and work. Sometimes that is a problem. It’s a lot of pressure. I want the excuse. I get frustrated with myself because I don’t have an idea or a destination yet. But when I do, I can flow right into it. It’s a space that really supports that.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

The final product is to support women — their bodies and their spirit. The whole notion is that a piece of clothing, for a woman, is a home to live in for the time that you have it on. This means it needs to feel good on you. You have to have a place to put your hand. It can’t be a place where you feel self-conscious in your garment. The beauty, and color, and uniqueness of the person who is inside is, hopefully, expressed on the outside.

This idea is contrary to how many of us are trained to understand clothing, e.g. suffering for beauty is OK.

It’s incorrect. If you’re at ease, you feel more beautiful. It supports that process of having the inside match the outside. Choosing to be known. My clothing is not shy. It’s a conversation starter. A lot of my designs come in my interest in travel: The motifs and the colors are drawn from all sorts of global references. So, you’re communicating all the time you’re in your clothing, and my job is to make something that communicates you. The other theme is celebration. I’ve always been a person who’s attracted to several colors at once. I love a single-color message, but I also love multi. Multi for the Japanese is the color combination that connotes celebration.

What prompts the beginning of a project?

A deadline. Even after being out of the business for so long. I designed four collections a year. I was always working toward the next show. That was in New York [City]. Jerry and I started by collaborating. He had a business designing and making women’s bags. He had a workshop, and started making one-of-a-kind clothing, which I sold for him in my [SOHO] showroom. My partner and I represented small designers working in their lofts off 7th Avenue, and one of them was Jerry. He also made a few pieces of clothing because he was an architect, and very interested in the human form. We began to collaborate behind the scenes on clothing I thought would sell well. It just ballooned, and we were in Harper’s Baazar, and Vogue. There was a heyday, which in fashion lasts about five minutes. Ours lasted about five years, and from then on it was just keeping up, and creating new things so people didn’t forget about us. At our largest, we made four different lines, and each one was sold separately. There was fall [collection], spring, summer, holiday — so we had at least four different iteration of the each label a year. I was responsible for making all that happen. Every once in a while I’d burn out and turn to Jerry for [help] with a new idea.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project?

When I was in business, I was preplanning all the time. You had to think about the fabrics you’d need, and order those things well in advance of getting to design the collection. I was always working on three or four things at a time, six months in advance. Now, I get ideas and picture things well in advance. Other times, I don’t have an idea. And, I pray. A lot. I don’t have a lot of deadlines now. I like projects and I like deadlines because that gives me an endpoint to go for.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Not if I don’t have to. It’s such a luxury to work on one thing at a time now. I can concentrate of it. I’m not pulled in 25,000 directions. I can be pulled in directions that are creative in different ways. That’s one of the wonderful things about being semi-retired — having space in your calendar for being pulled in a different direction entirely.

Process is an organic thing. If you have time, you have space in your brain to entertain things that aren’t on the check list.

When our [four] kids were young Jerry and I were very active in their school, and would collaborate with the teachers to do art projects. Inevitably, four days before the project commences I’m cursing myself, and wondering why I ever said I’d do this. Sure enough, it would happen. A week later, I was including everything I got from that process into my process at work. Everything feeds the process, whether you like it or not

Do you work in a series?

Yes. I do. Not always. Some of them are one-offs. I’m really good at iterations, at spinning an idea out. And, I love all the iterations.

[NOTE: Meg and Jerry never outsourced their clothing to manufacturers in China. It was designed and created in their studio workspace. “That’s why we liked making one-of-a-kinds,” Meg said.]What’s your favorite tool?

By far my rotary cutter. I do a lot cutting, and cutting is a big, big part of my work. You can make perfect curves with a clean edge. You can make imperfect curves. It’s a wonderful tool for fabric.

Do you use a sketchbook? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

No. I’m not a good draftsman. I use a sketchbook for notes, and little cartoons of what I’m trying to say when I can’t say it with words. I’m not well organized, so if I have something [in which to record ideas] it has to be something all together in a notebook. Usually, I’m just working with my stitcher, Shelley. We do verbal stuff. I just show her what I want.

How do you come up with a title?

I used to name the garments when I had to. When I was making a [clothing] line, and there were 12 pieces in a line, then the ones that were the showstoppers got named because people enjoyed the names. I could communicate some humor, some excitement, some joy, a deeper meaning, or a sense of adventure. A destination comes through a name.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

I won’t say it was a decision. I’ve always been practical in terms of: Can I make money with this? It was backwards in that I was making money, and I had my own business. I was lucky to find something I could do well. After I was a buyer with Nordstrom [Meg held a variety of positions with Nordstrom from 1974-78], I opened a showroom in New York with my friend, and we represented clothing designers to buyers — I’d been a buyer, so I could talk to them. And then, I started working with the designer on how to merchandise their ideas, how to communicate to buyers and make a collection that would tell a story on a retail floor.

Many people, when they think of a Capital “A” Artist, might not think that the business experiences you’ve described could inform a creative practice.

I would never have said there was a through line while I as doing it. There was a point in my early 30s when I looked back, and said, “Wow, I’m using everything I’ve learned thus far.” It’s a gift of hindsight. I would not have said I was aiming toward anything consciously. All of those jobs that I’ve described taught me how to work with other people, how to talk to other people, taught me about customer service, taught me about connecting with people, taught me about organization, gave me a view into other people’s process, helped me understand that I was value-added with other artists in helping them shape their practice. And, it wasn’t until I started working with Jerry, collaborating with him on pieces of clothing to sell in my showroom, that I grasped the fact that I had a point of view that was important in this collaboration.

The second thing that really brought the whole thing full circle was when Jerry found on Crosby Street two old silk screens that were advertisement for T-shirts. He brought them to the studio and asked if I knew how to silk screen print, and could we figure out a way to use these? We threw some fabric down on the floor and screened our first piece. I thought: This is something that I learned [13 years earlier in college]. I can add something that is so dear to me.

Talk about making your own materials as opposed to sourcing all the materials for your work and cutting it off the bolt.

The main impetus for that was that we lived in a neighborhood that was filled with jobbers. Jobbers bought secondhand fabric off of manufacturers, and sold it to other people. This was an important part of the garment industry in New York. These guys had filled their buildings with fabrics. Over years. Decades. They had all sorts of fabrics that would not be suitable to use for other people — they had stains on them, they were white. But we could transform them, and they were cheap. We started dyeing fabrics, and we would print fabrics. We came up with several different techniques for printing. That allowed us to buy other people’s leftovers.

The economics of this are obvious. The other piece is that making your own materials gives you a unique, visual voice.

Over the period of time we were in business, we had so many people copy us, which was supposed to be a form of flattery. But nobody could really do what we did. We did so many different transformational things to our clothing. The clothing always looked different. That’s one of the things that kept us alive for so long — we could draw on so many different [surface design] techniques. It couldn’t really be copied.

What role does social media play in your practice?

About zero. I’m on Facebook and Instagram, but I don’t post my work. When we moved out here I made a decision I didn’t want to grow my business anymore. I didn’t have to. And, I wasn’t going to take jobs for money if I didn’t want them. If anything I had to make a decision not to have a website or have a business card. I wanted to narrow my work to that which I only wanted to do.

What do you believe is the visual creative practitioner’s role in the world?

Art is expression and communication. It’s very different for other people. All art helps people connect with their feelings, and identify with what’s going on out there. Words don’t cut it at times — although writers help me connect with my feelings. But it helps people feel their feelings by identifying with an image, or a film, a song, or a book — that’s why art is so profound, and joyful, and devastating. I don’t think many artists think of themselves as having a purpose, but they can’t help it.

What parts of the world find their way into your work?

I was lucky. My grandmother was a docent at the Honolulu Museum of Art when I was kid, and because of that, [she] populated our house with a lot of Japanese art. That really influenced me. My mom always says, “I’m not an artist. I don’t know where you girls got this.” And I used to say to Mom, “Mom! You taught me to look.” She was all about getting us to look at things. The National Geographic! I’d pore over that. It’s just a feast, the world.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

That’s a really interesting question for me. When we would come out here in the summer, we’d manage to get away from the business for a month, and the whole family would come out here. We would have all sorts of projects, which we wouldn’t finish because we had to go to the beach. I found, when I would come here, I would have these incredible surges of creativity, and I would have to find something to do with it. For three years I painted the concrete foundation of our barn, with a fake stone foundation. That’s the name of our farm now: Fake Rock Farm. I can’t attribute the location as the entire reason, but it was a place that engendered creativity for me. Also, we were living in New York. We were bombarded by stimulation there, and visual information and noise, and intense amounts of things that would compete with our basic creative urges. Coming out here gave me space to listen. In moving here, it has been an entirely different experience than coming here for bits and pieces of time. In the winter the palette is both stultifying and supportive of my need for color. I have to say also the landscape has created more nuance in my palette, and sense of patterning. Northern Michigan has given me space and time.

[NOTE: Meg and Jerry began vacationing in Leelanau County in 1988. They moved permanently to Maple City in 2021.]

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

If I did, I didn’t see it as a creative practice. We knew artsy people, but I didn’t know the practice behind [their art-making].

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I talked about my teacher at Smith who waved a magic wand and told me I was a creative being, who supported my eye, and said I had a good eye. My mother always telling us to look. My grandmother had so much style. My uncle owned the first showroom in San Francisco that represents Knoll Furniture, and he had an incredible eye. My first significant boyfriend is a painter, and he painted no matter what. He now hangs in The Met, and has an amazing career. He showed me perseverance. I also have to say that Jerry taught me to work on something every day.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

The market decides that. If I’m really stuck, I’ll reach out, but I almost never show my work to anybody until it’s done. When I had my business there was a tribunal that looked at the collection when it was all done, and made edits, and that was pure torture, but necessary. I learned you had to have a thick skin. I learned, doing that work over and over and over again, that you surrender work. You let go of it.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

In my clothing work it was sales. “Exhibiting” took place at trade shows. I had my first show-show with six of my other Smith friends when we went back to Smith for our 45th reunion. We had a show of all work we done as adults in our adult careers. It was one of scariest thing I’ve ever done. And, it was one of the most joyous things I’ve ever done. It was a lot of work, and I had to explain all the things I chose to exhibit. You have conversation with yourself about how you’re not worth it. I think artists are incredibly courageous to put a piece of you up on a wall and say this is me, and open yourself up to god knows what.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

With everything. When you open up your ears eyes and mouth, you’re feeding yourself. If you’re listening, you’re feeding yourself. Going to museums. Travel. And, when I get to a hump in the creative process, when I have that self-talk — I am not an artist, I can’t come up with a new idea, what was I thinking — I think of service, of doing service. If I am in service to the universe, and in fact to women, I can do anything.

What in the world drives your impulse to make?

Inextricable to my career is making money. But I had not been making art per se for 13 years. I was looking to get back to my creative self when Jerry and I started collaborating. I’d been in a creative dance with people, thinking creatively, but not in a hands-on way. What drives the impulse to make is not making for a while. It gets bottled up, and I just have to do it.

Read more about Meg Staley here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Larry Fox

“I’ve always built things. I’ve been a maker since I was a little kid,” said Leelanau County artist Larry Fox, 69. And the things he has built — sculptural constructions in Poplar and Baltic Birch — have found their way into homes and corporate settings across the US. A veteran of the art fair circuit, Fox has traveled far and wide with his trailer full of work inspired by architectural shapes, cracks in the parking lot pavement, and what he discovers when he falls into a creative pothole. Fox’s work is all about dimensional shape. “I’m attracted to dimension,” he said. And it was dimension that brought him and his family to Northern MIchigan in 1989.

This interview was conducted in February 2023 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured left: Larry Fox

You work in a sculptural form using wood.

Yes. Three-dimensional forms that are constructed out of wood, and primarily painted — as the finish.

And there are always lots of interesting marks on the surfaces of your sculptures.

A lot of that is a painting technique called dry brushing. I learned that from working on movie sets. It’s a loose type of painting. I also use colored pencils to enhance [the surface design] a little bit.

When did you work on movie sets, and where?

Mostly in Detroit. Small independents. Then I worked on a few big features around the country [including The Abyss, Tiger Town, and Stardust]. I was doing fine woodworking at the time — making furniture and building additions. This was in the 80s and 90s.

What draws you to working in wood , and working with wood in a sculptural way?

I can manipulate wood to satisfy my curiosity. My father had a shop, and as a young kid I was in the shop all the time. He was very giving about me playing around in there. That’s where [his interest in] wood came from — and the fact that it’s a natural material — as opposed to metal. I don’t find other materials attractive. Wood is warm. It’s growing. I love trees. The three-dimensional aspect: I’ve always been attracted to dimension. I grew up in Detroit, and it was totally flat. That’s one reason why I’m in Leelanau County: There’s some dimension to [the landscape]. I’ve been thinking about transitioning to painting as I get older, and I haven’t made that leap yet — because of the dimensional aspect …

It’s flat.

It’s flat!

What physical effects are you feeling that makes you consider leaping ship, and going to painting?

Getting out of bed every day. My body’s starting to hurt. I used to do a lot of really-big work [e.g. a 50 foot-long installation for GE Medical, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 2006]. I’ve curtailed that. I’m doing more bench work. I still have the desire [to work large], but not the energy.

Did your dad let you run power tools?

Oh, yeah. I was lucky I never did anything really bad. I would always take the tools, and try to push them: What can I do with this as opposed to just doing what you’re supposed to do? I would always push. I do that with my work.

You don’t allow yourself to be hemmed in by either the materials or the tools, or the conventional expectations of what both of those things can do.

To a degree, I do. You have to respect the materials and the tools. Every time you approach a power tool you have to be on your game. I appreciate that aspect of it. At the same time, the other side of my brain is going, What can you do with this that’s different?

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

I studied architecture for two years at Lawrence Tech. And then I went to the College For Creative Studies in industrial design. And then I got a degree from Wayne State in art education [1979]. I also went to Penland, and Haystack, which are craft schools. And an internship out in Canada at the Banff Art Center.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

It definitely contributed to my ability to use my talents.

It sounds like you may have learned a lot in the doing.

Yes. I would say mostly in the doing.

Describe your studio/work space.

It’s in a pole barn, and is a 24 feet by 24 feet. I have a room for painting and drawing. It’s 150 feet from my house. Half of it’s heated. When I first moved in, it did not have windows. I remember coming back from a funeral [25 years ago], and I said, I’ve got to put a window in that shop. So, I got a big window from somebody who was ripping down a big house. It overlooks all these pine trees, and it’s beautiful.

How does your studio/work space facilitate your work?

I’ve had six or seven studios in my life, everything from a garage to a studio in Suttons Bay [Michigan]. It can make it easier; but the actual work? It really doesn’t matter. You’ve got to have natural light. You’ve got to be relatively comfortable. But you can adapt to anything.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

A primary idea is one based on observation, [observing] form, pattern. If I see something — let’s say it’s a crack in the sidewalk, and I’ll say, That’s amazing. I’ll eventually interpret that [observation] into a piece. Sometimes I’ll want to tell a story, whether it’s political or human relations. There’s an architectural interest. I get ideas walking in the woods. There’s natural phenomena. There’s man-made phenomena. Pretty much everything.

It’s like you’re always punched in.

You are. It’s amazing. The key is, as soon as you see something, you’ve got to jot it down. You’ve got to sketch it on a piece of paper or wood. Then you put it away, and say, Someday I’ll make that.

I’m interested that you jot down inspirations. Cameras are ever present these days. Are you still a pencil-and-paper guy?

Oh yeah. Give me a legal pad and a Sharpie, and I’m happy. The pencil issue: I’ve always loved drawing. Even now, I don’t spend a lot of time drawing; but I do sketch out my work. Loosely. I’ve always loved that physicality of the pencil on the paper, and that texture of the paper is important. There’s a great joy to sit down and just draw some ideas down: That’s one of my favorite things to do.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

First you have to have the idea, the concept [and ask yourself] How am I going to interpret that concept in a physical form? You have to ask yourself what you want to say. What is this piece about? Is this a form piece? Or does it mean something? What is it? You take that thought pattern, and interpret into the shapes. I draw the piece as I build it. I see the piece graphically as I’m making it. And, sometimes I build and see that it’s not working, so I cut it in half, and now it works: You can’t always see it right away.

You work in wood. It takes a little courage to chop things up. Wood is a lot harder to put back together than a couple pieces of paper or fabric.

Not really. There is a little bit of a [psychologic] barrier. You try to talk yourself into [settling for a composition that doesn’t work by saying]: That’s OK. That looks pretty good. But you keep coming back to: That’s not OK. And so you go: I gotta do it. But you don’t want to do it because you’ve already put the time and effort into building it, and you know it’s not right.

Sometimes I see that as an opportunity to have a new creative thought. It ejects you from the path you were on, which is saying, You’re going in this direction. But then you hit a pothole.

And, sometimes, those potholes are fantastic. They make the piece. Sometimes your initial concept of the piece doesn’t quite work. It’s always about: How am I going to make this piece work? It’s not a black and white thing.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Rarely. I can’t multitask very well — unless it’s a process I have to let sit, and then I’ll go onto something else.

What’s your favorite tool?

Bandsaw.

Why’s that?

The freedom of it.

It’s a scary tool, with a band of sharp, fast-moving metal.

You always have to have your hands away from the blade. What that tool can do is incredible. It’s a blade and you can play with it. A lot of things I work on aren’t perfectly straight. There was time when that was different, but now my work is a lot looser.

Why is making things by hand important to you?

It’s key. Every time you make something, you’re creating something — whether it’s a chair or a table or a house. You had this idea, and you process it, and you make the thing. It’s an over-and-over cycle of burden. Here’s this new thing. It’s incredible.

Why does making by-hand remain valuable and vital to modern life?

From the beginning of time, it’s a human thing to use your hands — whether you’re gathering food, or you’re making a piece of art. I think a lot of people lose it, forget about it. But I think every human has that desire to make things.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

I did my student teaching, and I thought, I like making things better than teaching. As far as committing to it, after college I thought about being a self-employed woodworker. There was no [precipitating] event, but I had to make money, so I was going to do what I loved to do. I always dabbled in other things — film, film sets — but the other side of that, I was always making something — whether it was with 20 people or by myself.

What role does social media play in your practice?

A website is the beginning of that. You have to have a website. The website connects people with your work that would never see it, and is a reference once they have an interest in it. Other than that, if I’m doing a show, my social media director — who is my daughter [Lindsey, 31, also a visual artist] — she does all the [social media promotional] stuff on Instagram.

Do you use social media to tell the world about your work, or look for inspiration?

No. I try to stay off it. I have to admit that I’m as curious as the next person, and sometimes you see stuff that’s really cool. But I don’t like going there.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

People who make things, artists, they can show me things I might not even think of. [They] broaden your view of the world, and [they] open up a bigger picture.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

Living up here allows me to have a lot of time to pursue the work I want to do, uninterrupted, and a low-key, very low-key, lifestyle. It [allows him] to clear my head, and have a clean palette to work with. Lots of times, you end up living where you went on vacation as a kid. I came up north on vacation when I was a kid. I grew up in Detroit, so I also have a big-city fix I have to satisfy every so often. When I did more [art fairs] I used to get that satisfied. Now, [his life] is a little isolated as I get older. It’s very quiet up here in the winter. I gotta get out more.

You’ve shown your work on the air fair circuit for decades. What kind of job is that for a guy to have?

The beauty of that whole [art fair] world is it allows you to do what you love to do. Now, traveling to the shows and selling the work — I’ve never liked that. I’m introverted. I have to get into my extrovert mode to do that. As a general thing, it’s not my favorite part of the business.

You get a lot of immediate feedback about your work on the air fair circuit. You come face-to-face with a lot of human beings who are looking at your work.

You have to put on your sales-person hat, and it’s really important what you say and how you present yourself. I can do it occasionally. I like the idea that the work sells itself, but that’s not really true: You have to engage and say the right thing. That’s the part of the business I’m not really crazy about. I’ve struggled with it. I’ve been [working the art fair circuit] for about 30 years now.

Do you exhibit at art fairs year-round? Do you do that trek to Florida to do all the shows in that state?

I used to do it every year, but I’m kind-of done with Florida. I did that for 20 years.

When you were growing up, did you know anyone with a serious, creative practice?

My dad loved making things, but everything was by-the-book. My mom was a Sunday painter. Most people asked me, What are you doing? You can’t be an artist. When are you going to get a real job. I heard that a lot.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work?

My heroes, in the historical sense, are Frank Lloyd Wright, Louise Nevelson, the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava.

To whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

At this point, my daughter, Martha [his wife], and my son Jesse [27]. He’s really good with proportion and forms.

What is the role of exhibiting in your practice? Do you ever exhibit your work in museum or gallery shows?

Yes. It’s getting eyes on your work.

Tell me how you fuel and nurture your creativity.

I do it by taking hikes, going skiing, reading.

Walking in parking lots looking for cracks in the pavement?

Exactly. I don’t directly try to nurture my creativity. I’ve never had to. It’s hard to answer that. You go through hills and valleys of creativity. Sometimes, when I’m in a valley, I go, I haven’t really thought of any good ideas in the last month. But I don’t go, I’ve gotta do something to nurture it. All of a sudden, there will be another wave. I can’t tell you what promotes that.

You work, mostly, in a non-representational fashion. Why is that the best way for you to execute ideas — as opposed to trying to make something that someone will say, A-ha! That’s a chair!

Whenever I was in drawing class, there were compositions or human forms, and you’re supposed to capture that — the proportions, the feelings. When I make stuff, I don’t want to be tied to [its realism]: That’s a horse, or that’s a hill. I just want to make an interpretation of [an object or subject]. It frees you up. It’s partially due to my limited technical abilities — that’s why I switched from fine woodworking to what I do now. Technically, it’s not that challenging, but artistically, it’s more challenging. It’s a lot more fun. Harder to sell, but it’s a lot more fun.

Read more about Larry Fox here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

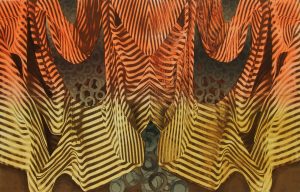

Creativity Q+A with Dorothy Anderson Grow

As part of the exhibition Ropes, Ribbons, Twigs, and Things in the GAAC’s Lobby Gallery, Traverse City artist Dorothy Anderson Grow talked with Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, about the venerable art of printmaking as she practices it with 21st century tools and materials. Dorothy maintains an active practice focused entirely on printmaking. Working in her home-based studio, she creates hand-pulled, one-of-a-kind prints full of bold shapes, colors, and the sensation of texture. Ropes, Ribbons, Twigs, and Things is on display September 2 through December 15, 2022.

Describe the process of making an intaglio etching plate.

Initially, I create an image. I work and think both abstractly and non-objectively. My images may begin both the familiar or unfamiliar; real or unreal. My inspiration can come from such things as ribbons, ropes, fabric, twigs, clay forms, or my own drawings. In order to input these images into my computer and began the process of making an etching plate, they need to be photographed. For me photography is a tool not an outcome. It’s absolutely necessary that I use photography for my process. That’s the only way I can load an image into my computer so that I can make a transparency, and a print.

So, you’re not taking dictation. The photograph is just a way to record or generate an image on which you do more work.

Given my generation, working from photographs was a no-no. You had to be more creative. Some realistic things are reproduced in my work now, but it’s not like I’m copying from a photograph.

Once in the computer, I use Photoshop to recreate, manipulate, distort, and arrive at an 8” by 10” composition. I work in gray scale with no color. Color enters into my thoughts later when I am inking the etching plates. So for now, I am using the computer (another tool) to produce an 8” by 10” clear transparency with black ink only (like in the first photo). My second step is to create the etching plate (second photo). Instead of using the old traditional method of engraving metal plates with toxic chemicals, I use a DuPont film [known commercially as ImagOn] on a plastic plate, a UV light, and soda ash to create a toxic free plate. There is a lot of equipment, timing, testing and chemistry that goes behind this method. Some printmakers use a similar and simpler method called Solarplate. The plates are already prepared and use only sunlight to develop them. I find them far more costly and not as controllable. On step three, once the plate is made, it needs to be hand inked and tested on my printing press. If the print details are not clear enough, I need to recalculate and go back to step two.

How is the plate hand inked and transferred onto paper?

This is the long awaited step in my printing process. To hand ink a plate, I mix a color and spread the water based ink over the plate. I use a form of cheese cloth to rub off the excess ink and continue to whip the plate with recycled paper to clean the raised surfaces. The ink will remain in the recessed areas that are etched out. When the plate is placed in the bed of the press, a sheet of printing paper is laid over top. In order for the paper to pick up the recessed ink from the etching groves, a felt blanket is placed on top. As the drum rolls over the paper, the pressure creates an intaglio print.

At times, I will ink up to eight 8” by 10” plates and place them next to each other of the bed of the press to create a final 16” by 32” print. The number and how I place these plates will determine if I have a large or small; symmetrical or asymmetrical print. The initial etched prints are only the first step to my finished work.

What media and concepts do you apply to make the final work?

This final stage is the most exciting. There are several techniques I use and I am always experimenting with new ideas. I usually start by adding blends of color with an inked brayer onto a sheet of Plexiglass producing a monotype. I will also, at times, go back into the etching with colored pencils to create some shading effects or clearer definitions. Not all the details in the etching plate come out perfect, so I check for detail. I touch up the gaps. I will also try to shade, although it’s hard to shade into a print.

Next, collage elements are critical to my thinking which add elements of juxtaposition and interest. Many of the collage pieces are inkjet printed sections of my previous prints, modifications of color and scale of the current print, or a newly formed image. I also add textures created from ink, paint, and a variety of sources. Conceptually, my goal is to arrive at a new and unknown place.

Using all these tools and processes, I want to create a visual form of communication that’s stands apart from other ways of communicating. To me art is a language with a visual vocabulary

How have printmaking supplies and methods evolved since you have studied printmaking?

The most relevant change for me has been the switch from oil based inks to water based inks. The new Akua inks will remain moist for five years if not in contact with paper or cloth. They print on dry paper (Arches 55), as opposed to soaked paper. They are nontoxic. I have already mentioned the safe way of making etching plates with film versus acid etching. Also, I attended a lithography workshop a couple of years ago where an image is printed onto a rubbery type surface from a computer printer instead of the traditional hand drawn image on a stone or metal sheet. It is amazing how much technology has effected the visual arts.

After 30 years as a painter, you decided to concentrate 100% on printmaking. Why?

I loved being a nonobjective painter. But also during my past years of study and two degrees in art [a BA/Art Education from Baylor University, 1965; an MFA from Michigan State University, 1976], I had also studied several types of printmaking. I found that my processes with painting and printmaking were quiet similar. Printmaking had evolved from a toxic art media into a safe media. Slowly, I began experimenting with forms of collagraph and monotype [printing], and found them challenging.

While I was teaching art at Northwestern Michigan College [1999 – 2005], I enrolled in Photoshop and other computer graphic classes. I searched for a way to incorporate these new skills into my printmaking. I then discovered ImagOn. DuPont had collaborated with Keith Howard from Rochester Institute of Technological and developed a film and technique to produce toxic free etching plates. Using this new process, I was able to apply my new computer knowledge. This became my new focus.

Some of your work is translated into a three-dimensional print. Talk about that.

This courage came gradually. I had been a member of the Washington Printmakers Gallery in Washington D.C. for several years when I began taking my printmaking seriously. The gallery held a very traditional view of what types of prints were acceptable. Prints needed to be matted and framed according to a specific standard and computer generated inkjet prints were not allowed. Since then, they have expanded their views and so have I. I began by creating wall relief prints without frames and eventually free standing prints with multiple views.

But because these three-dimensional works are intaglio prints, they needed to be printed first on my etching press. The idea was to combine several two- dimensional prints together. This was a very exciting move for me. I would print out several 8” by 10” sheets of paper containing the etching image and then cut, fold, bend and glue the pieces together. Because the majority of my prints are symmetrical, this was an advantage. So compositionally, my current three-dimensional works are an extension of the processes and techniques I use on my two-dimensional pieces. I have future ideas of creating asymmetrical 3-D work and prints on cloth.

Where and how did you learn to print? Formal training?

In my undergraduate studies in art education and studio art, I was exposed to relief printmaking like linoleum block printing. In graduate school, I did extensive coursework in screen printing. Post graduate, I studied several intaglio forms of printmaking including collagraph, monotype, etching, and embossing. Once I decided to make intaglio printmaking my focus, I had to search for these new processes on my own. Since there is very little intaglio printmaking happening in this area, I traveled to instructional workshops in Santa Fe, New Mexico and spent a month of immersion in Italy.

The subject, and title, of this exhibition is ropes, ribbons, twigs and things. What is it about these objects and shapes that interest you?

I began studying art following the Abstract Expressionism period. Most of my creative thoughts were grounded in Formalistic thinking.

Explain what you mean by the term “formalistic thinking.”

As opposed to creating art to tell a story, to represent an image, or to promote a cause, I create art so that I can use the elements of visual art to compose and create something new. The colors, the shapes, the forms, how they interact with each another, and how the outcome arrives: that’s formalism.

So today, I still find myself searching for pure visual expression in abstracted realism or non-representational art. My art is not about social change, political ideas, environmental awareness, or other commendable issues.

As my work has evolved, I am currently working with imagery that is non-solid, stringy, flexible, and temporary. They can be twisted, tied, folded, curled, or looped. They can be tangled, intertwined, overlapped, or repeated. Many of the images are familiar and relate to my past. Once items of my childhood play, they are now a part of my serious art. I am so excited that these images transcend into the three-dimensional realm.

Read more about Dorothy Anderson Grow’s work here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates exhibitions for the Glen Arbor Arts Center. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

Creativity Q+A with Nancy Crisp

Nancy Crisp, 81, taught visual art to all ages, and abilities, in public school and private institutions, from the 1960s until 2003. Her own visual art education began in junior high, guided by a teacher who grounded her in the fundamentals. Now, her painting practice unfolds in a home studio she shares with her husband, a ping pong table, and more. Regardless of the other roles the studio plays, it’s the exact, right place to consider what’s developing on the canvas. “A lot of painting time is thinking time,” she said.

This interview was conducted in April 2023 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Left: Nancy Crisp

Describe the medium in which you work.

In the last, few years of painting, it’s acrylic. I’m a big acrylic fan. It’s my paint of choice, and I love it. Occasionally I mix it with oil-on-top, but rarely. And, sometimes I [add] collage to acrylic [paintings], which is very adaptable to that.

What is it about acrylic that speaks to you?

When I went to college, it was just at the cusp of acrylic coming in. It’s the drying time: I love [acrylic’s] expediency. I can put paint on. I can cover it up quickly, so it’s easy to layer. Layering is my thing.

Tell me about your formal training in visual art.

I started at a college out East, and took classes there but realized they were limited. I switched to [the University of Michigan], and loved the art department. I got my MA there, in painting and sculpture [1964].

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I had more training in high school than I did at the university. In my graduate program, we were totally on our own. I saw my graduate teacher once a semester — he’d come in, and we’d talk about everything but painting. When I graduated, I felt I needed to self-teach a lot — I did a lot of reading. I had a fantastic art teacher [in both junior high and high school, in Midland, Michigan]. Charles Breed went with us from seventh grade through 12th. The greatest gift that he gave [his students] was a real sense of composition. Charles included the elements of design (point, line, shape, volume and space) as well as the principles (center of interest, balance, focal point, rhythm, contrast and unity) in all our projects in all mediums.We didn’t do any painting in his class, but we worked with all kinds of other materials.

When I was in grad school, I loved being there. If somebody would have footed the bill, I would have stayed there for the rest of my life as a student. I think what happened in graduate school is — I’m a fairly shy person, and I did not do what a graduate student should do: They’re the ones who should go out seeking the knowledge, but I expected [instructors] to bring it to me. I didn’t ask questions.

Describe your studio/work space.

My work space is huge. We live in a very strange building that was built as a chicken coop. They sold eggs out of it. There were about 5,000 chickens at one point. It’s 185 feet long. The front third [of the building] is our living area. There is a 35 foot x 35 foot studio area that we [Nancy, and her husband, Howard] share. It was supposed to be mine.

How does your studio space facilitate your work?

I was able to go larger [4 feet x 6 feet — up from, for instance, 12 inches x 24 inches], which I wouldn’t have been able to do. I love that I can walk through the door, and I’m in my studio. That makes a lot of difference. I can pop in, do a lot of thinking, or maybe put a few brushstrokes on a canvas, and then pop back out [into their living space].

Does it ever feel, with your studio space being in such close, physical proximity, that your studio is breathing down your neck, and you can’t get away from it?

I’ve never had that feeling. We do our recycling in the studio. We play ping pong in the studio. It’s used for other things. And whatever I go in there for, I’m studying the paintings while I’m doing something else. It gives me more think-time on them.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

That always changes. I went through a long period of painting abstractly — using the paint, and seeing where the paint took me, and then would develop a composition from that without a theme in mind. Now I seem to have issues I want to talk about in the painting, like the environment, places I’ve been, or experiences.

What prompts a change in your focus?

That could be anything. I don’t have a straight line in my development. It depends upon whatever is in my visual and emotional life.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

I rarely work from a drawing. I’m all over the place. I don’t have a method I go to to develop a painting. It’s pretty much all emotional response, not an intellectual delving-into.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

I often work on two paintings at a time just so I can use up leftover paint. It’s always good to have something new on the horizon. If one painting isn’t working well, I can switch to another. A lot of painting time is thinking time. That’s almost as important as the painting time, being aware of what’s going on and taking time to figure out where I’m going — because I usually don’t know until I get there.

What’s your favorite tool?

All my brushes. I don’t paint with a palette knife. All my good-sized brushes from my U of M days are there, and I’m still working with them.

Do you use a sketchbook, or a work journal?

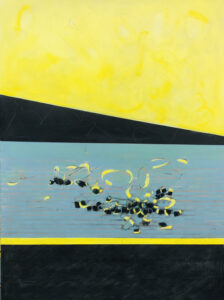

Sometimes I do sketches, and sometimes I do paintings from the sketches. Swimming In The Heat started out to be a simple line sketch of the beach and the hills. But as I worked on it, I began thinking about the environment, and how much I loved any view of Lake Michigan and the shoreline and hills, and all of a sudden, my sketch turned into a cautionary tale about heat. Usually if I work from a sketch, it’s a starting point. But I don’t usually work from a sketch. I usually start out with paint.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? And what were the circumstances?

I don’t know if I ever consciously made that decision. I was fortunate to have a mom who was an artist, too. She started us painting before I had memory. I don’t think there was ever a point when it wasn’t part of my life. It was always an activity that was valued in my household.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Probably none.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

I think the visual artist’s role in the world is to be as true to themselves as they can be, and find their own voice. Whatever is personal is often universal.

What parts of the world find their way into your work?

Before the 2016 presidential election, I reacted very strongly, and my paintings were about that.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

By looking out the window right now, I see buds starting. We go through all the seasons. We’re not urban. We’re in this beautiful country. It — the landscape — has to influence us. It would be hard not to. When I’m out in nature, or walking the streets, I’m always seeing line, texture, color. When I walk with somebody else, they have to listen to me as I talk about it.

Did you know any practicing studio artists when you were growing up?

My mom, and then my beloved art teacher, Charles Breed. He was a huge influence. He worked in a studio in Midland, and it was open to artists. It was a communal thing, so we were able to see him work, be with him while he was working. There was a core group of student who followed him through junior high and high school. We had dinner with him. We went to his cabin and studio on Long Lake [in Traverse City]. It was a warm and inclusive experience.

Lots of time we don’t have access to adults who can model the work we want to do. If you want to be a dentist, it’s fairly easy to find a practicing dentist from whom you can learn what a dentist does. In the visual arts: not so much.

I think that’s true. We mostly work in our private spaces. Having those few years where there are other artists coming into [the Midland studio spaces] was a rare opportunity. Now I realize I had that. Most of the time, creating is very lonely. You’re in a studio by yourself.

Where, or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

I have friends, and I have my husband who’s number one. He’s very honest with his feedback.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

That’s been a changing role. It’s hard in this area. There was a time when there was a thriving art community, and we had [the Traverse City] arts council. There were frequent opportunities to exhibit. [But, she said, the exhibition opportunities in local galleries are harder to find.]

Why do you want to exhibit your work?

At some point one wants to have other people see it. We do it because we want to share it, and get response. It’s part of our identity. If no one sees it, how do we carry that identity if it’s only us [seeing our own work]?

There are many exhibition opportunities beyond Northern Michigan. Talk about how you feel about trying to find a place to exhibit outside your community.

There are lots of opportunities, which require an exceeding amount of work — filling out the forms, and then you have to ship your things, which involves expense and time taken away from other things you want to do. You aren’t guaranteed that after you’ve gone through the expense of applying that your work will be accepted. It needs to be sent back, or you have to go down and bring it back. I’m down to exhibiting locally. That’s what I spent my energy on.

You hit on a lot of things that illustrate that a studio practice isn’t all glamor — the yeoman work of applying, and packaging, and shipping.

No. It’s not.

How do you nurture and fuel your creativity?

I’m fortunate to be married to an artist. We both respond to the visual world. We’re both, often, working in the studio, and will react to each other’s work. That’s just part of what’s happening in this household. Through the years, many of our friends are also in the art world. I’ve done a few workshops in the past.

When you were teaching, what challenges did teaching present to you practicing your own work?

The big challenge was time. Teaching was very time consuming. My last 15 years were in the public schools. During that nine-month period, my days started pretty early, and I usually didn’t get home until 6 pm. There wasn’t really time to do art. In summer, I felt I had the opportunity to do the most work. Now, I have day after day after day to go into the studio. I may not paint every day, but I at least think every day.

How did your teaching activities cross pollinate with your studio activities?

Part of my mind was always [focused] on teaching art, on line and color and composition and shape, and working with different materials, and responding to what was happening with the children, and being encouraging. I always felt like I was thinking of art, and it paid off when I went into the studio. I didn’t feel like it was taking away from my making of art.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.