Creativity Q+A with Meg Staley

There has never been a straight line through Meg Staley’s career. But every experience — from sale clerk, to department store clothing buyer, to printmaker — has factored into the creative work she now does. The Leelanau County artist hand builds women’s clothing. Each piece is a composition that allows Meg, 70, to bring to it the myriad surface design techniques that make up her distinctive visual vocabulary. This is not, however, a story about fashion, but a life-long journey that uses clothing as an expressive tool. This interview took place in April 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

Several. Textile, printmaking, surface design 2 + 3 D, and clothing design.

You don’t work in a single medium. Talk about how all the things that comprise your practice, and how they draw you into them.

I don’t know what a “normal artist” is. And, I’ve never thought of myself as an artist. Period. I would say, in terms of the visual, it’s the texture, and color, and pattern that my mixture of media makes me happy. As far as motivation, it’s practical: It was money. A way in which I could express myself that was in service of women.

How was your work “in service of women”? How did you serve women through your clothing?

Because my early work was in building clothing for women — myself, and then for others. It’s been a life-long journey. I was always, from an early age, very, very excited by clothing. And I could easily wear clothing, and found myself making it for myself. Then, as I went on, I realized women — in general — would ask me style questions. And, through my first career at Nordstrom, I was a salesperson, and I went into fitting rooms with women, helping them find something they’re happy in. I realized women have all sorts of stories about their bodies, and what they don’t like. I got good at helping women find things that made them feel pretty. I was lucky enough, in my 20s, to put together a number of different jobs, in different places, in different aspects, to begin to understand that I could do something with that skill. When I got to a point where I could apply some of my skill set in terms of sewing, and making, and building, and printmaking, and all these other aspects of what I’d learned into designing for women, I understood that I had a mission.

You said you never thought of yourself as “an artist.” Talk about that.

My older sister showed a very early talent for representational art. She could draw a picture, and it looked like the thing. And, then she studied art. That was my interpretation of what an artist was. So, my sister was the artist in the family, and you know [siblings] can’t have the same roles. Even with a sewing machine, and sewing lessons, I was the only person who had ever sewed. I learned to sew, but in those days [in the 1950s and 1960s], that was not art. That was a craft that women did. So I didn’t ever associate it with art. That was my early story I told myself about not being an artist.

Was an “artist” something you wanted to be?

I wanted to be anything my sister was. In fact, telling on myself, there was this women who lived across the street from us in Bellevue, Washington, who was a cartoonist. I copied some cartoons and took the sketches over to her, and told her I’d sketched them. She told my parents she thought I was very talented. That’s part of my story, wanting to be something that I’m not, and not being happy with who I am.

Have you achieved the level of “artist”? Have you been admitted to the club yet?

Yes — because my definition has changed. Anybody who thinks a thought, sings a song, writes a sentence is an artist. I think of myself as a creative, sentient being. If you want to call that an “artist,” great, I’ll take it.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

That wasn’t until I was lucky enough to go to Smith College, which had a great art department. I learned there that art history was something — I never knew that was a thing. I took music history. I took music composition. I found out that all these things I was interested in were things [one could] study. Also, I took a drawing class in sophomore year — when I found all the things I thought I was supposed to study required so much reading, and I was not a fast reader. I thought I needed something I could do besides read. I had this wonderful [drawing] teacher. He was practitioner, and worked for Hallmark Cards. He was not considered a Ph.D guy — he was a practitioner. He taught me how to see differently. The following year, I took a composition course from him. He told me I had a great eye, and he thought I should pursue an art major. He was a major influence. And, he’d come from a very different background: He was not a fine artist. He was a commercial artist. He gave me a stamp of approval about the way I look at the world. I studied mostly photography and serigraphy [screen printing]. By the time I graduated [in 1973] I was a printmaker.

You use silkscreen printing in your business, Meg Staley Handmade.

During my business of 30 years, we did a ton of silk-screening on fabrics, and I collected more than 500 images that I still have. I have this library of single-color images. I could easily make new images, but I have such an amazing library that I use my favorites over and over again on fabric. I cut up the printed fabric, and utilize it on different places on a garment.

I began collaborating and making things [with her husband, Jerry Gretzinger] in 1985 [as Staley Gretzinger Inc.]. We sold the business [in 2008], and I had to come up with a different name for myself. I wanted and needed to continue practicing. I needed to make money, so I started a new label: Meg Staley Handmade. It started out being women’s clothing, and branched out to many things — home goods, soft bedding, quilts, patchwork pillows. That has grown into a lot of commission work for people who have lost loved ones. [She makes] legacy quilts, keepsakes — that’s very important work for me now. I get to work with an individual, and process with them their loss, and work with them to make something that has meaning for them. But I still make women’s clothing because it’s fun.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

When I went to Smith and began to study art, I was very influenced by my peers and classmates. I watched their process. I watched them not give up. I watched them come at a problem from a different angle. I watched them permutate their work in several different direction, and realized there’s no one way to make art. I never thought I’d make a career or a profession of it. I always thought it would be relegated to something that maybe I’d be lucky enough to play around with at some point. Serigraphy requires space. And it requires equipment. All art[making] has certain requirements, but this thing that I loved had a high threshold for practicing. I thought this was something I was going to have to say goodbye to. Thirteen years [after graduating] I started silkscreening again.

Describe your studio/work space.

It’s very me. If color is my religion, then my studio is my chapel. My studio is four miles away [from her home] in Cedar, Michigan. It’s an old general store built in 1909. It still has all its original floor, ceiling, and the original store front windows. It’s right on the main street of Cedar, two door down from the Cedar Tavern, and across the street from Blue Moon Ice Cream. When I try to describe where I am to the locals, those are the two reference points I use. The workable space is probably1,000 square feet, and then I have a whole basement.

The studio is so many things to me. It’s a place I can be by myself with my own music, puttering without any destination in mind. It’s sanctuary that way, and a celebration. In the middle of winter in Northern Michigan, and we’re all cooped up in our homes, it’s a place for me to go that’s filled with color and memories, and objects, and things hanging, and all of my favorite toys. It’s such a luxury for me. It’s the first space I’ve ever had that was really designed for me. We put in a big slop sink, and a big commercial dryer for setting inks, and a washing machine. I have tons of table space, tons of storage. Every other space I’ve worked in has been carved out of something more important. Or, it has been a living space, and I convert the dining room table into a print table, and then back again and put it all away. This has been a huge acknowledgment for me that I’m worth it. It also makes me incredibly happy.

Your studio is on the main drag in Cedar. What’s your relationship with the public walking by?

Initially I thought I could do a little store here. And, I quickly remembered my frustration and impatience being at Nordstrom, having people walk in the midst of me making an incredible display, interrupting my artist process, and wanting me to help them. I don’t need to do retail anymore, and I don’t want to. I have one [Leelanau County] store that carries my work [Ruth Conklin Gallery], so I can tell people who want to buy my work to go to that store.

One of the things about having this space is that there are no barriers/excuses for getting work done. I don’t have to reset it up. I don’t have to do a whole lot to get myself ready to work. I can just walk in there and work. Sometimes that is a problem. It’s a lot of pressure. I want the excuse. I get frustrated with myself because I don’t have an idea or a destination yet. But when I do, I can flow right into it. It’s a space that really supports that.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

The final product is to support women — their bodies and their spirit. The whole notion is that a piece of clothing, for a woman, is a home to live in for the time that you have it on. This means it needs to feel good on you. You have to have a place to put your hand. It can’t be a place where you feel self-conscious in your garment. The beauty, and color, and uniqueness of the person who is inside is, hopefully, expressed on the outside.

This idea is contrary to how many of us are trained to understand clothing, e.g. suffering for beauty is OK.

It’s incorrect. If you’re at ease, you feel more beautiful. It supports that process of having the inside match the outside. Choosing to be known. My clothing is not shy. It’s a conversation starter. A lot of my designs come in my interest in travel: The motifs and the colors are drawn from all sorts of global references. So, you’re communicating all the time you’re in your clothing, and my job is to make something that communicates you. The other theme is celebration. I’ve always been a person who’s attracted to several colors at once. I love a single-color message, but I also love multi. Multi for the Japanese is the color combination that connotes celebration.

What prompts the beginning of a project?

A deadline. Even after being out of the business for so long. I designed four collections a year. I was always working toward the next show. That was in New York [City]. Jerry and I started by collaborating. He had a business designing and making women’s bags. He had a workshop, and started making one-of-a-kind clothing, which I sold for him in my [SOHO] showroom. My partner and I represented small designers working in their lofts off 7th Avenue, and one of them was Jerry. He also made a few pieces of clothing because he was an architect, and very interested in the human form. We began to collaborate behind the scenes on clothing I thought would sell well. It just ballooned, and we were in Harper’s Baazar, and Vogue. There was a heyday, which in fashion lasts about five minutes. Ours lasted about five years, and from then on it was just keeping up, and creating new things so people didn’t forget about us. At our largest, we made four different lines, and each one was sold separately. There was fall [collection], spring, summer, holiday — so we had at least four different iteration of the each label a year. I was responsible for making all that happen. Every once in a while I’d burn out and turn to Jerry for [help] with a new idea.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project?

When I was in business, I was preplanning all the time. You had to think about the fabrics you’d need, and order those things well in advance of getting to design the collection. I was always working on three or four things at a time, six months in advance. Now, I get ideas and picture things well in advance. Other times, I don’t have an idea. And, I pray. A lot. I don’t have a lot of deadlines now. I like projects and I like deadlines because that gives me an endpoint to go for.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Not if I don’t have to. It’s such a luxury to work on one thing at a time now. I can concentrate of it. I’m not pulled in 25,000 directions. I can be pulled in directions that are creative in different ways. That’s one of the wonderful things about being semi-retired — having space in your calendar for being pulled in a different direction entirely.

Process is an organic thing. If you have time, you have space in your brain to entertain things that aren’t on the check list.

When our [four] kids were young Jerry and I were very active in their school, and would collaborate with the teachers to do art projects. Inevitably, four days before the project commences I’m cursing myself, and wondering why I ever said I’d do this. Sure enough, it would happen. A week later, I was including everything I got from that process into my process at work. Everything feeds the process, whether you like it or not

Do you work in a series?

Yes. I do. Not always. Some of them are one-offs. I’m really good at iterations, at spinning an idea out. And, I love all the iterations.

[NOTE: Meg and Jerry never outsourced their clothing to manufacturers in China. It was designed and created in their studio workspace. “That’s why we liked making one-of-a-kinds,” Meg said.]What’s your favorite tool?

By far my rotary cutter. I do a lot cutting, and cutting is a big, big part of my work. You can make perfect curves with a clean edge. You can make imperfect curves. It’s a wonderful tool for fabric.

Do you use a sketchbook? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

No. I’m not a good draftsman. I use a sketchbook for notes, and little cartoons of what I’m trying to say when I can’t say it with words. I’m not well organized, so if I have something [in which to record ideas] it has to be something all together in a notebook. Usually, I’m just working with my stitcher, Shelley. We do verbal stuff. I just show her what I want.

How do you come up with a title?

I used to name the garments when I had to. When I was making a [clothing] line, and there were 12 pieces in a line, then the ones that were the showstoppers got named because people enjoyed the names. I could communicate some humor, some excitement, some joy, a deeper meaning, or a sense of adventure. A destination comes through a name.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

I won’t say it was a decision. I’ve always been practical in terms of: Can I make money with this? It was backwards in that I was making money, and I had my own business. I was lucky to find something I could do well. After I was a buyer with Nordstrom [Meg held a variety of positions with Nordstrom from 1974-78], I opened a showroom in New York with my friend, and we represented clothing designers to buyers — I’d been a buyer, so I could talk to them. And then, I started working with the designer on how to merchandise their ideas, how to communicate to buyers and make a collection that would tell a story on a retail floor.

Many people, when they think of a Capital “A” Artist, might not think that the business experiences you’ve described could inform a creative practice.

I would never have said there was a through line while I as doing it. There was a point in my early 30s when I looked back, and said, “Wow, I’m using everything I’ve learned thus far.” It’s a gift of hindsight. I would not have said I was aiming toward anything consciously. All of those jobs that I’ve described taught me how to work with other people, how to talk to other people, taught me about customer service, taught me about connecting with people, taught me about organization, gave me a view into other people’s process, helped me understand that I was value-added with other artists in helping them shape their practice. And, it wasn’t until I started working with Jerry, collaborating with him on pieces of clothing to sell in my showroom, that I grasped the fact that I had a point of view that was important in this collaboration.

The second thing that really brought the whole thing full circle was when Jerry found on Crosby Street two old silk screens that were advertisement for T-shirts. He brought them to the studio and asked if I knew how to silk screen print, and could we figure out a way to use these? We threw some fabric down on the floor and screened our first piece. I thought: This is something that I learned [13 years earlier in college]. I can add something that is so dear to me.

Talk about making your own materials as opposed to sourcing all the materials for your work and cutting it off the bolt.

The main impetus for that was that we lived in a neighborhood that was filled with jobbers. Jobbers bought secondhand fabric off of manufacturers, and sold it to other people. This was an important part of the garment industry in New York. These guys had filled their buildings with fabrics. Over years. Decades. They had all sorts of fabrics that would not be suitable to use for other people — they had stains on them, they were white. But we could transform them, and they were cheap. We started dyeing fabrics, and we would print fabrics. We came up with several different techniques for printing. That allowed us to buy other people’s leftovers.

The economics of this are obvious. The other piece is that making your own materials gives you a unique, visual voice.

Over the period of time we were in business, we had so many people copy us, which was supposed to be a form of flattery. But nobody could really do what we did. We did so many different transformational things to our clothing. The clothing always looked different. That’s one of the things that kept us alive for so long — we could draw on so many different [surface design] techniques. It couldn’t really be copied.

What role does social media play in your practice?

About zero. I’m on Facebook and Instagram, but I don’t post my work. When we moved out here I made a decision I didn’t want to grow my business anymore. I didn’t have to. And, I wasn’t going to take jobs for money if I didn’t want them. If anything I had to make a decision not to have a website or have a business card. I wanted to narrow my work to that which I only wanted to do.

What do you believe is the visual creative practitioner’s role in the world?

Art is expression and communication. It’s very different for other people. All art helps people connect with their feelings, and identify with what’s going on out there. Words don’t cut it at times — although writers help me connect with my feelings. But it helps people feel their feelings by identifying with an image, or a film, a song, or a book — that’s why art is so profound, and joyful, and devastating. I don’t think many artists think of themselves as having a purpose, but they can’t help it.

What parts of the world find their way into your work?

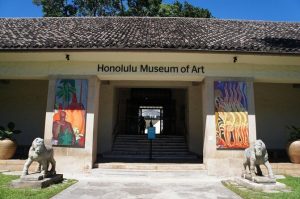

I was lucky. My grandmother was a docent at the Honolulu Museum of Art when I was kid, and because of that, [she] populated our house with a lot of Japanese art. That really influenced me. My mom always says, “I’m not an artist. I don’t know where you girls got this.” And I used to say to Mom, “Mom! You taught me to look.” She was all about getting us to look at things. The National Geographic! I’d pore over that. It’s just a feast, the world.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

That’s a really interesting question for me. When we would come out here in the summer, we’d manage to get away from the business for a month, and the whole family would come out here. We would have all sorts of projects, which we wouldn’t finish because we had to go to the beach. I found, when I would come here, I would have these incredible surges of creativity, and I would have to find something to do with it. For three years I painted the concrete foundation of our barn, with a fake stone foundation. That’s the name of our farm now: Fake Rock Farm. I can’t attribute the location as the entire reason, but it was a place that engendered creativity for me. Also, we were living in New York. We were bombarded by stimulation there, and visual information and noise, and intense amounts of things that would compete with our basic creative urges. Coming out here gave me space to listen. In moving here, it has been an entirely different experience than coming here for bits and pieces of time. In the winter the palette is both stultifying and supportive of my need for color. I have to say also the landscape has created more nuance in my palette, and sense of patterning. Northern Michigan has given me space and time.

[NOTE: Meg and Jerry began vacationing in Leelanau County in 1988. They moved permanently to Maple City in 2021.]

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

If I did, I didn’t see it as a creative practice. We knew artsy people, but I didn’t know the practice behind [their art-making].

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I talked about my teacher at Smith who waved a magic wand and told me I was a creative being, who supported my eye, and said I had a good eye. My mother always telling us to look. My grandmother had so much style. My uncle owned the first showroom in San Francisco that represents Knoll Furniture, and he had an incredible eye. My first significant boyfriend is a painter, and he painted no matter what. He now hangs in The Met, and has an amazing career. He showed me perseverance. I also have to say that Jerry taught me to work on something every day.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

The market decides that. If I’m really stuck, I’ll reach out, but I almost never show my work to anybody until it’s done. When I had my business there was a tribunal that looked at the collection when it was all done, and made edits, and that was pure torture, but necessary. I learned you had to have a thick skin. I learned, doing that work over and over and over again, that you surrender work. You let go of it.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

In my clothing work it was sales. “Exhibiting” took place at trade shows. I had my first show-show with six of my other Smith friends when we went back to Smith for our 45th reunion. We had a show of all work we done as adults in our adult careers. It was one of scariest thing I’ve ever done. And, it was one of the most joyous things I’ve ever done. It was a lot of work, and I had to explain all the things I chose to exhibit. You have conversation with yourself about how you’re not worth it. I think artists are incredibly courageous to put a piece of you up on a wall and say this is me, and open yourself up to god knows what.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

With everything. When you open up your ears eyes and mouth, you’re feeding yourself. If you’re listening, you’re feeding yourself. Going to museums. Travel. And, when I get to a hump in the creative process, when I have that self-talk — I am not an artist, I can’t come up with a new idea, what was I thinking — I think of service, of doing service. If I am in service to the universe, and in fact to women, I can do anything.

What in the world drives your impulse to make?

Inextricable to my career is making money. But I had not been making art per se for 13 years. I was looking to get back to my creative self when Jerry and I started collaborating. I’d been in a creative dance with people, thinking creatively, but not in a hands-on way. What drives the impulse to make is not making for a while. It gets bottled up, and I just have to do it.

Read more about Meg Staley here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.