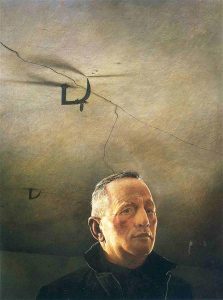

Well into his career as an advertising executive, Hank Feeley, 84, wondered if he’d taken the wrong fork in the road. Wonder led to action: He hung up his business suit and enrolled in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. A painting hobby became a professional practice. Making, he said, is “what human beings are supposed to do.”

This interview was conducted in April 2025 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Hank Feeley

Describe the medium in which you work. What is your work?

I’m mainly a painter: 60% oil, 20% acrylic. The rest, watercolor and pastel. I also sculpt, but not much these days. I used to do a lot casting in bronze and lead crystal when I was in Chicago, but I’m not there anymore, not close to the foundries. What I’ve been doing [instead] is using Sculpy. You don’t need a foundry, but an oven to bake it.

When you decide you want to work in sculpture, what’s the thing the thing that says to you, “This needs to be a sculpture.”

I don’t think of it that way. I’m painting, painting, painting, and then I’m having down time, and I think I haven’t done a lot of sculpture recently, so I take it up. It’s almost on a whim. Painting is my main business. So I take it as a break, an interruption, a change. Something to stimulate a different part of the brain.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

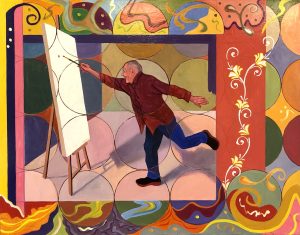

When I was 2 or 3 years old, I had some cousins who would babysit me. They went on to become successful commercial artists. They got me interested in art. I wouldn’t call it “formal” training, but they began the process in my life. I became a pretty good painter in my teenage and college years. Then, I figured I’d make that a career, so I went into the advertising business with the idea of being an art director. Somebody was making three times what I was making down in the research department. I went down there, interviewed, and ended up working for 30 years on the business side [of advertising with the corporation Leo Burnett], not the creative [side], not being an artist but around a lot of artists. It always bothered me that maybe I’d taken the wrong fork in the road. I did art while I was in the advertising business, but it was a hobby. I got to a point where I decided — financially and otherwise — that I could take the fork I didn’t take originally. My office was across the street from the Art Institute of Chicago. I started taking classes (1993-1995). Eventually, I quit my business and went full-time. I got a BFA in studio art, and one in art history.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

It changed everything. I always painted and drew, because I could. I didn’t ever think about art history, what other people did. When I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago [SAIC], I took a lot of art history, which really changed everything for me. It was a revelation — seeing what other people had done and understanding why they did it. For instance: I never liked Picasso. I didn’t understand him. After art history, understanding these artists, what they were trying to do, and the groundbreaking innovation and creativity — it changed everything for me. It changed my art. The other thing is the students I was going to school with were younger than my own kids: wide open, creative, experimental people. The SAIC really didn’t want to train a watercolor painter like me. They wanted to train the next Picasso. These creative kids influenced me a lot. So, I started experimenting a lot, tried to stretch the envelope.

You have two studios. One in Northern Michigan, and one in Florida.

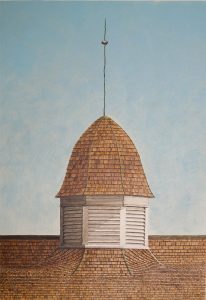

The one in Florida is a second-floor, storefront operation, about 800 square feet. It’s a good space. I designed the one in Michigan — I’m a frustrated architect. It’s a cool place. I love being there. It’s built like a barn. It’s heavy-timber construction that old barns were made from. The doors open to the outside. Also, I use it as a storage space. Right now my boat and my cars are in there. It’s my home base.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

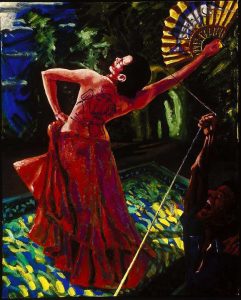

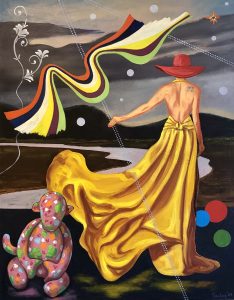

I started out doing themes; back in those days, it was music. I always play jazz when I’m painting, and I started painting with the music, and got musically-looking kind of work. I did that for while, and then I moved into something called The Red Dress: I did about 40 paintings [in which] a red dress was involved. Then I got into things based on the information age.

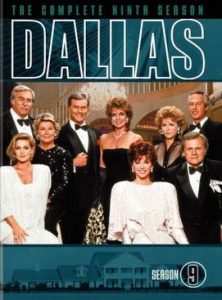

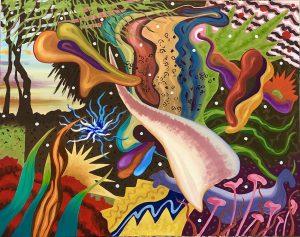

Years ago, when I was [still in the advertising business], we went to Venezuela. They had had a monsoon, and it had wiped out all these indigenous people who lived in the mountains. They had no electricity, no water, nothing. When we went there [with medicine and food], we observed one group of people who [had pirated] electricity from the government lines along the road. They were watching, on little rabbit-ears TV, Dallas. It was a paradox. It was like, What’s going on here? People who have nothing and are starving and have no water, are watching a television show about the most affluent people in America. It stunned me. Years later, it occurred to me, in the age of technology, that people around the world see things that are totally incongruous, different to what their lives are. I made a bunch of paintings about it. I still do that if an issue comes up. I make the contrast between my life, and what’s happening in the rest of the world. It was a theme that gripped me, but you run out of steam. You do 60 of these paintings in a row, and you decide that you’ve done it. At that point I decided that I wouldn’t have themes anymore. I’d just get away from themes and just dream. That’s mostly what I do now. And, the way I achieve that: Over many years, I’m an inveterate collector of images. I have 14 boxes of images that I’ve pulled out of newspapers, or sketches I’ve made, or photographs. They catch my eye; I don’t know what I’m going to do with them, so I just throw them into the box. If I’m looking for an idea, I sit down and go through the box. These images were isolated when I first picked them out, but now they’ve gotten shuffled with other images, and I look at them in a different light. That becomes the spark, the new idea.

Years ago, when I was [still in the advertising business], we went to Venezuela. They had had a monsoon, and it had wiped out all these indigenous people who lived in the mountains. They had no electricity, no water, nothing. When we went there [with medicine and food], we observed one group of people who [had pirated] electricity from the government lines along the road. They were watching, on little rabbit-ears TV, Dallas. It was a paradox. It was like, What’s going on here? People who have nothing and are starving and have no water, are watching a television show about the most affluent people in America. It stunned me. Years later, it occurred to me, in the age of technology, that people around the world see things that are totally incongruous, different to what their lives are. I made a bunch of paintings about it. I still do that if an issue comes up. I make the contrast between my life, and what’s happening in the rest of the world. It was a theme that gripped me, but you run out of steam. You do 60 of these paintings in a row, and you decide that you’ve done it. At that point I decided that I wouldn’t have themes anymore. I’d just get away from themes and just dream. That’s mostly what I do now. And, the way I achieve that: Over many years, I’m an inveterate collector of images. I have 14 boxes of images that I’ve pulled out of newspapers, or sketches I’ve made, or photographs. They catch my eye; I don’t know what I’m going to do with them, so I just throw them into the box. If I’m looking for an idea, I sit down and go through the box. These images were isolated when I first picked them out, but now they’ve gotten shuffled with other images, and I look at them in a different light. That becomes the spark, the new idea.

In so many of your paintings, there are symbols and images and icons and people scattered throughout the composition. It’s surreal. They don’t, at first glance, seem to be related to one another.

What’s your favorite tool?

I’m a painter. It’s brushes, obviously.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal?

I occasionally do some sketching. [Mostly,] I put things together in my mind. I have some beginning ideas. Sometimes I sketch things out. Like a figure. I want to sketch out the figure before I do it, to get it accurate. Believe me, I don’t know what the painting is going to be once it starts. I keep manipulating it until I don’t know what else to do.

This would stand in direct opposition to the work done in an advertising agency where everything is plotted out, you think through the strategy, and nothing’s left to chance.

That’s true. My work [in the studio] is totally open ended. In the advertising business there’s always an end in sight. It’s an entirely different thought process. I live in two different worlds.

Do you feel comfortable living in two different worlds?

It’s interesting. I have two different names. My professional name as an artist and advertising person is Hank. But among friends from high school and college, I’m Chips. My business friends, they’re interested in productivity, and how long does it take me to make it? And, how many do I make in a year? I have no idea. It’s not the way an artist thinks. It’s funny — the way they [people in business] think and how an artist thinks, and I have both of these in my mind.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Zero. I don’t do Facebook. I don’t do Instagram. I don’t have any relationship to it. I have a website that my daughter-in-law put together for me about 20 years ago, and it has never changed. It has [a tab] that says “About Hank Feeley,” and when you click on it, it says, “Information to come.” When people ask me for my website, I tell them to Google me. All the information about me comes through the galleries that represent me. They put it all out there. I’m too old to deal with that stuff.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

To make us better humans. It stimulates our better emotions. It causes us to wonder. It makes us more empathetic, more collaborative, more willing to listen. When you say that, you ask what the hell is the government doing defunding the arts?* It just doesn’t make sense. If you’re going to have peace in the world, you’ve got to have that collaboration and empathy — the things that art stimulates.

[*Beginning in the mid-1950s, the State Department realized the potential of jazz to build bridges with other nations, and started sending jazz musicians on state-sponsored tours of the USSR and the Middle East. PBS made a film about it.]

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

I like to think that all parts of the world do. I try to be very observant, very engaged with the world. I’m particularly good at catching visual things. I read a lot. I love poetry. That all enters my art.

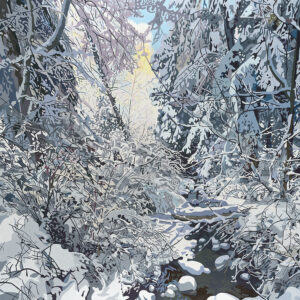

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s indirect. I do go out and do landscape painting, but I’m mainly a studio artist. The stuff I do Florida and the stuff I do in Michigan is the same. But I will say this about where I live both in Florida and Michigan: It’s great to live in a community that appreciates art, where there are other artists to engage with. That keeps you fresh and stimulated — aside from the beauty of Northern Michigan and Leelanau County. It’s just a comfort to live here.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

My two cousins who started me out were artist types, and went on to become professional artists. In the advertising business, you’re dealing everyday with artists. Many of the artists I dealt with in the business were, outside of that, serious fine artists. They did a lot of their own art and had gallery shows. When I went to the SAIC, the professors — some were my age, some were younger than me — I became very close to many of them: Ted Halkin, Dan Guston, the Chicago Imagists, Barbara Rossi, Ed Paschke. My art was highly influenced by their thought process. All their art was different, but they had a good thought process: invent things, create, experiment.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

That’s a problem for me now. When I lived in Chicago — I haven’t had a residence in Chicago for about six years — I used to be in contact with some of the people I knew from the SAIC. They’d come to my studio, look at my work, and we’d talk. I don’t do that much anymore, and I miss it.

What role does exhibiting play in your practice?

Once a year I’m in a show in New York or Chicago. I want people to see what I’m doing. And, I especially want other artists to see what I’m doing. It goes back to what we were saying: Maybe somebody will become a better human because I’ve touched their emotions, I’ve made them think about art a lot more.

How do you fuel and nurture your creativity?

I look at what I do as a job. You show up in the morning, and you do your work. Some days you don’t feel like doing it, but you do because it’s your job. I’m in my studio every day — every day I’m not playing golf, which is on Wednesdays — and I start working. I don’t think in terms of waiting for inspiration; if you wait for inspiration, you’ll never get anything done. What you do is you work, and as you work, maybe something inspiring happens. But you have to put in the hours, put in the time, put in the dedication. I think of it that way.

Even though you’re putting out a lot of creative energy, it doesn’t sound as though you’re draining the well.

I don’t feel drained. A very good friend of mine who’s an artist said the way to live is to have a creative thought every day. It’s a regimen. Now, sometimes it’s hard to have a creative thought every day, but that’s your job and you’ve got to do it. So, I come in [to the studio] and I’ve got nothing going on, and I need to have some stimulus: I go to my boxes. That’s the great thing I have with these boxes. I can spend a day going through them, and all of a sudden: Boom! Let’s try this! Let’s try that. And bang! I’m off painting again.

What drives your impulse to make?

This goes back to being a human. Humans have always made. It’s in our nature. I’m doing what human beings are supposed to do. That’s what has made our world.

Learn more about Hank Feeley here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.