Creativity Q+A with Justin Shull

Traverse City painter Justin Shull “knew, even in high school, that I really wanted to be making visual art in some capacity.” And, that’s the course the 41-year-old artist set: a 2004 BA in Studio Art from Dartmouth College [Hanover, New Hampshire], followed by a 2009 MFA in Visual Arts from Rutgers University [New Brunswick, New Jersey]. But road blocks, and side roads, and other impediments got between him and total studio immersion. Now, he’s free to practice, and this is what he has learned.

This interview was conducted in January 2024 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Justin Shull

What is your work?

For the past three years I’ve worked full-time as a fine artist. Prior to that, my last role was product manager for a video company, Riot Games.

Any male, age 12 – 25 has heard of the game [he worked on]. It’s called League of Legends. It’s an online multi-player game, kind of a fantasy-based capture the flag with very deep strategy. I joined the company in 2011 when they were small — about 100 employees — and the company grew to about 3,500 employees world-wide, and had about 350 million monthly players at one point. Quite a large game. Very popular.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I knew, even in high school, that I really wanted to be making visual art in some capacity. But I thought then it was something I did along side or parallel to whatever profession I’d choose. At the time I was in engineering, then pre-med. I explored a lot of different directions and ended up studying studio art [undergraduate studies], and then going back after some time in the work force to do my MFA. I thought I wanted to teach, and be in higher education, and surrounded by that environment and be part of that community. What I enjoyed about undergrad, graduate school and teaching was the ability to explore visually, wherever your creative sensibility took you — there’s no market pressures in that. A good portion of my creative journey has been within that context, and it has only been in recent time that I’ve been trying to make work that connects more directly with a market.

What did you take away from school that you now see is part of the way you practice in your studio?

One of the dominant mindsets coming out of the academic environment is to focus narrowly, and in a very rational, research-based approach. I’m still deciding if that’s the right way for me to work. Very often, it doesn’t seem like the right way to work because I have found I tend to work on multiple series in parallel, that are only tangentially related, and that actually have to develop on their own over time. Having to describe them up front as [an academic] thesis is not the right way to arrive at the best work. That’s one thing that has taken me years to figure out in terms of what was the dominant framework for working in academia — versus creating a work flow and an approach that works in the studio. That was really important because how you structure your approach to work, and how you constrain or not constrain yourself, has a big impact on outcomes over time. I want to say I received a lot of technical, hands-on education around how to use the media, and I did not. Most of the programs are much more focused on the conceptual side, and they leave it to the students to figure out the medium.

Why do you think that is?

I think it’s a pendulum-swing reaction to the over-emphasis on a singular approach to the medium, which defined academies for centuries. There was a really strong reaction to that through Abstract Expressionism [to the present time]. There are programs that really stress how to, for instance, develop your facility with oil paint. But a lot of programs do not.

Do you work in oil, or acrylic, or both?

In undergraduate I worked primarily in oil paint until I developed a severe sensitivity. I’ve been limited in my ability to use oil paint since then. I only work with it outdoors now. But there are a couple of painting that I’m working on [in the studio] that are going to require some oil paint. As a medium there are certain things I can do with it optically that I can’t with acrylic. I tend to look at whether I’m using acrylic paint, or oil paint, or another medium in part [determined by] what that medium allows me to do visually, and in part what’s contained in that medium from an historical context.

Give me one example of what you can do with oil paint.

Because oil paint has a longer working time, you can use soft brushes to achieve very subtle gradations and blends that you cannot with acrylic. There are more recent developments with the open [acrylic] paints that let you begin to approximate that; but there is something about the way the oil blends materially and optically that lends itself to certain applications.

Describe your studio.

I work in a live-work space in the Tru Fit Trouser Building in Traverse City. In total, it’s about 1,300 square feet. I have about 700 square feet of that set up as a studio. I’ve been in this space for two year, and I specifically wanted to work out of this space because of its tall, white walls. There’s really a flexible track lighting system with high CRI [color rendering index] lights so I can approximate what larger work would look like hanging in a gallery. For me, that was part of the process of working up in scale, and developing studio work — not just landscapes rooted in outdoor observation.

You’re able to bring the landscape ideas inside, and complete them in the studio — as opposed to confining yourself to plein air painting.

Yes. Plein air painting is a great exercise in staying calm, collected, and focused on translating my experience of the space around me in real-time, navigating changing light and sometimes challenging weather conditions, and maintaining the mindset that my primary objective is to observe and translate spontaneously in a way that ultimately will be inviting to re-discover later (both for me and any other viewer) versus falling into the trap of going out to “make a good painting” or to “make a painting that will sell.” Everything I learn while painting en plein air filters into my studio work, but for me the studio is a place where ideas can unfold at a much slower pace, sometimes even over the course of years. I might develop a digital sketch over the course of a few weeks and then return to that idea a few years later to make a painting based on that sketch and the painting is then able to unfold into its own self and perhaps push some of those ideas even further. And more recently in the past year, branch out from landscape altogether into a more figurative, allegorical series.

You have been known as a “landscape painter.” You exhibited a piece in the GAAC’s 2023 Swimming exhibition that suggested you were trying to get out of the landscape silo, to explore other themes and subjects. How hard is it, when one is known as one thing, to start moving in other directions?

I’m still learning that. There’s a couple of different axes on which you can answer. One: It can be quite easy, if you’re just talking about making work. I can go into the studio and make something completely different. That part is easy. But then there’s the question of how it’s received? How do meet expectations, or not meet expectations, and how do people respond. That’s the part I’m still figuring out. Much of work from the last year I have available on the web through a couple of private viewing rooms, but I haven’t posted it my website yet. That’s one of my big project this year, to decide how I want to integrate, or not, those different bodies of work. There’s value in looking at historical examples of how people had multiple, diverse bodies of work versus a singular body of work. But then, I can decide that even if that didn’t work for someone, I’m going to make it work this way.

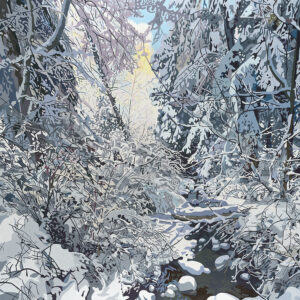

You paint landscapes in lots of lovely, luscious color. You’re also painting landscape in winter in a primarily black and white palette. Usually, when people paint the landscape that do that when it’s sunny, 70 degrees, and the world is in bloom. You, however, are finding something very paintable in a starker landscape. Talk about that.

The root of that is I don’t actually see myself as painting the landscape. What I see myself doing is painting my response, my representation of my experience of the world, which manifests in different ways. One is interaction with a landscape. One is interaction with various media, technologies. I always look at the landscapes I paint as metaphors for some other state of being, or mindset, or philosophy, and that creates a lot of space for working with different [seasonal] lighting conditions, subject matter within the landscape that might not be there to celebrate the sunny day, but be there to speak to our human experience as we move through the world. That’s how I come to the landscape. And then, of course, the audience will take different things away as well. That’s the beauty of it — there’s always room for a range of interpretation once the artwork is out in the world.

What’s your favorite tool?

My favorite tool is my projector. It allows me to accomplish a lot more than I would otherwise accomplish. In the history of larger-scale public painting there’s always the question of transfer, and how one scales their design — work at a small scale to work at a public scale. Digital projectors are amazing. I can make a drawing, a collage, an iPad drawing. I can combine them all. I can take that to an 8 ft. x 8 ft. canvas. I don’t have to sit there and grid out — for hours and hours and hours. In that way, it’s a productivity tool. It also helps you see things in a new way very quickly. And, I try to be really upfront that I use a projector in my work. When you start to talk about tools and methods, artists can very quickly start to splinter into ideological camps. I like to have that conversation with people who might not like to embrace photography as a source, or certain technologies. I’m happy to talk with anyone — especially people working in the Western traditions, the centuries of utilizing optical tools in the studio.

The distinction I hear you making is this: The machine isn’t doing the heavy creative lifting. It’s helping facilitate your expression of your original work. I think that’s where the conversation begins to get into “explain yourself” territory.

To our point, the bigger theme is the conscious choice as to which technologies we use, and to what extent efficiency is the goal. There are times when efficiency gains are really useful. And there are times when being in the middle of something, and having to make a decision with your hands is very useful.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I have a couple spiral bound sketchbooks. One of them I use to do color tests with paints. One of them I use to sketch out ideas. Then, I also will physically collage materials together — one-off pieces — that I collect and put into a photo portfolio at the end of the year. And, I also have a digital sketch pad.

You’ve created murals. You’ve worked as part of a video game start-up, and you’ve taught visual art at a number of universities. When did you decide to jettison these kinds of work, and commit to working with serious intent as a studio artist?

Coming out of undergrad I already felt that, if I had the choice, my priority would be maintaining a studio practice as a primary pursuit. It was a question of financial practicality, which it wasn’t [for Justin] for a good 15 years. After a few years of teaching through the financial crisis in 2008, 2009, my mentors [at Southern Methodist University (SMU) and Texas Christian University (SMU)] who were going to be retiring, chose not to retire, and they gave the feedback that if I couldn’t sustain myself [as an adjunct instructor], I should do something else. That got me out of teaching. As far as working in the video games goes, it’s difficult to work at a start-up part-time. It was really, for many years, all or nothing. I [eventually] tapered off to a part-time consulting role [with Riot Games], and then was able to paint. I’d stopped making art. It around 2017 I started painting again, and I knew it was going to be a few years, minimum, before I could produce work that I could bring to gallery. Coming out of the financial crisis, a lot of institutions decided to lean more heavily on adjunct instructors, and begin tapering back and eliminating tenured [positions]. The whole model and ecosystem of tenured-track positions changed dramatically.

How did teaching cross-pollinate with making your own work? And, how did teaching get in the way of you making your own work?

What I like about teaching is you have the opportunity to always be learning something new about some method or software or conceptual approach — if you want to. There’s this ongoing embrace of curiosity and learning that can cross-pollinate, between students and educators. There is an atmosphere of possibility in the classroom, with younger students. Those are things I really enjoyed. In reality, the world of an adjunct instructor is pretty difficult. You’re teaching two-three times the course load of an associate or tenured professor, and very often trying to find additional income — just from a practical standpoint — on top of teaching. When I was teaching, I was teaching six classes a semester, and also had a part-time job. As you can image, if you want to be making work, or if you have any aspirations to have a family life, those things can quickly come in conflict. The practical application of the current [teaching] model is that it does not create space or time or ideal energy to make the best work. That’s just the reality.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

There are different roles the visual arts play in our lives, as creators and as audiences, and a lot of people can engage with the visual arts and benefit from the creative process and how it affects their day-to-day approach to navigating their lives. And then there’s the question of: What role the visual artist plays in attempting to reach a broader audience, and be part of a broader conversation. That’s always up for debate, and always evolving. In the best scenarios, those individuals help us to understand what it means to be human, and to understand what our value systems and belief constructs are; and help us think about how we’re navigating the world. That’s pretty lofty, but I think, at best, what the visual arts, what other arts, can do.

You’re not creating work that attempts to be photographic in its precision. You’re creating work that provides people with a visual of how you’re interpreting the world. Lots of times, people who work in the visual arts see things differently, or see different things, and give viewers an opportunity to think about, for instance, the start beauty of a black-and-white landscape in the winter.

There is a certain satisfaction or joy that comes from being able to replicate a photograph. My goal is not to replicate a photograph. Photography and optical image projection, for me, are all tools. The image I ultimately create is a personal reflection.

What parts of the world find their way into your work?

Personally, one of the principles guiding my choice of colors, is the physiological effect color can have on us. Very often, the reactions a viewer is having to the colors in my work are connected to the types of experiences I’m trying to reference in the first experience of a location or a place. It might not be initially evident. Another thing that comes into a number of my landscapes is this idea of the intersection or interaction of our ordering of the world around us, and the natural logo or structure it pushes back with, and the dynamic balance — or lack of balance — between those two. There’s so many different ways to get at that.

On your website, you talked about direct observation: “ … my studies with Stanley Lewis at Dartmouth College and Chautauqua School of Art instilled in me the importance of direct observation, and introduced me to the amazing range of potential expression within this tradition.” Elucidate.

We can create space, and a sense of place completely from our imagination. Or, through strict adherence to shapes and colors that we observe directly. One of things I appreciated about Stanley was his commitment to going outside every day and working on a painting for two months straight, through changing weather and light conditions, and attempting to bring that experience into a single image — that was this condensation of time. My first exposure to folks going outdoors to paint was the Impressionists, and a lot of that work was really quick. To see this range of folks going out to experience the landscape directly, to capture their experience of it directly, for me that was a real revelation.

Why is there benefit in directly experiencing something?

I see value in personal, authentic, individual processing of then world around us rather than consuming what we’re told to consume.

How does Northern Michigan inform and/or find its way into your work?

I moved to Northern Michigan in 2018 from Los Angeles, and I arrived here with really fresh eyes. I wasn’t familiar with the landscape. I wasn’t familiar with the light. I wasn’t familiar with the history of [the place] and how the space had built up. It was a real joy, and it has been a real joy, being here, responding to that, taking it in for the first time. I’m actually noticing now, as I become more familiar with it, that’s become harder to do; and I’m going to have to change my approach in some way to keep the work, or the way I respond to it, fresh. But that took a good five years or so before I began to feel that. One of the things I’ve enjoyed about moving to different parts of the country, and seeing different parts of the world over the past 20 year, each time you land somewhere, you’re able to look at it with fresh eyes. I’ve found that that’s really important to learning how to look honestly. For me, it’s about true discovery, and authentically analyzing, thinking about, and interpreting in a way that is often unexpected, [as opposed to] digesting something in way you’re told to digest it.

Who has had the greatest, and most lasting influence on your work?

Oddly, or not oddly, Frank Stella. I discovered his work in high school. His work, formally, I admired; but also, the lasting impression comes from the very dramatic way his work evolved into different pursuits over time — starting as a formal minimalist working his way into something of a maximalist and working from very flat images to 3D sculptural work. Just as a role model, with the variety of work an individual’s career over time can embody — that’s stuck with me. That ties back to the question of: What do you do when somebody knows you as doing this thing, and you start doing that thing? There are some people, from an early age, I admired in their ability to follow their pursuits authentically even if it meant confusing expectations.

To whom do you go when you need honest feedback?

I’m always trying to expand the range of people I can get honest feedback from. I tend to lean on the friends I went to grad school with, and mentors who I studied with, and close friends. Those tend to be the people I can ask, Take a look at this, what do you think? Ask me some tough questions. Or, let me know when you think something is not working. I enjoy when a good friend will call out that they don’t like what I’m doing, or it doesn’t work. I usually respond to that better. It’s a challenge to articulate why I made the decisions I made, and to figure out if I’m going to push further into that until it’s doing what I want it to do. Or, abandon something.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

In the ideal world exhibiting artwork is, selfishly, a way for me to get real-world feedback from people about how they’re reacting to the work, and what they get from it. Sometimes that happens. I get the best feedback when I’m in-person with the work, doing a gallery walk-through and giving people additional context about the work. You really only get that through an exhibition space. I have my studio set up partially like an exhibition space, but there’s a lot more variables having your work out in the real world not knowing whose going to come into the gallery or art center and see it.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I try to expose myself constantly to other people’s work, and keep it dialed in so I’m not overwhelmed, but able to challenge myself through other people’s work as much as possible. The other thing I’ve found is really important is making sure I make time for other things — physical activity, athletics, just getting outside and wandering and giving myself time to not have to talk to other people. Just being in your head and letting yourself wander are important aspects of being able to foster creativity.

What drives your impulse to make?

I think it’s to find shared meaning and shared understanding. At it’s core, that’s the impulse to make — which is to put something out into the world, and find someone who says, Oh yeah! Or: I didn’t see it that way. At the end of the day, it’s a social activity, even if done in isolation.

Learn more about Justin Shull here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.