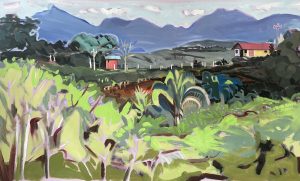

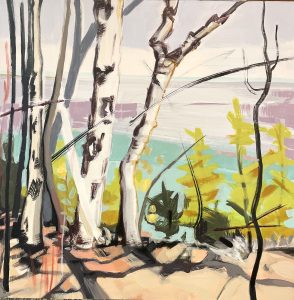

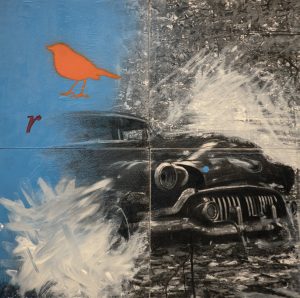

Painter Lauren Everett Finn, 64, isn’t shy about mixing her media. In any given composition, the Benzie County artist [pictured left] might develop an idea by collaging an element to the canvas. Or, add some marks made in pencil, crayon or oil stick. Lauren uses “whatever’s handy” to bring to fruition the idea she wants to explore. The same applies to the tools she uses in her practice: Paint brush and human hand have equal value. This interview took place in June 2022. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

You work in a lot of media. Do you consider yourself a painter? Or, other?

I think I’m still a painter. Most of the building-up of layers [with other media takes place] underneath [the composition]. What’s on top is paint.

What draws you to all these materials that you use?

It’s the “what ifs.” I wonder what would happen if: this is on top of that, and that is on top of that. Some of [the results] you can predict just with your experience. But sometimes you get something unexpected, which is a treat. Lately I’ve been using this tissue paper that doesn’t melt with water. It’s hardy. But when you collage it [onto a painting], it disappears — other than what you’ve painted on top of [the tissue paper]. Can you do that right on the painting? Yes. That’s an option, but sometimes you’re toward the end [of a composition], and need a little something, and don’t want to risk going hog wild [on the surface of the almost-finished painting].

Why do you like painting?

It’s the actual process. The paint. The feel of it. The opacity. The transparency. Color mixing. It’s so versatile — that’s the main reason. Yeah. It’s my jam.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

No. I graduated with a degree in advertising from Michigan State [1979]. I took one art class in college, and I’m blaming the instructor: I absolutely hated it. It was awful. I couldn’t understand what he wanted. That was very frustrating for me. I don’t know if he was talking over my head at that point. I’d played around in high school [Rochester High School, Rochester, Michigan], I didn’t do a ton of art until after I got my first job doing drafting [with a small engineering firm in Birmingham, Michigan]. And then, realizing I could draw and see 3-D, I did pen-and-ink house portraits [1981-1984]. That was such a fabulous way to learn how to paint because it was just value, no color. We [Lauren and her husband, Don] moved around the Midwest a bit, doing the house portraits as a side business as we moved yearly, and then we moved back to Michigan. I wanted to learn color, so I started taking classes at Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center.

Explain what the house portraits were about.

Since you did not receive formal training, how did you learn the craft behind your medium?

At [community] art centers. Also, I have the most ginormous art book library. Anything that looked slightly interesting, I would buy the art book. I have two huge book cases. I keep trying to pare down, and I’m having a really hard time. Even now, I’ll randomly grab a book, and just flip through — I count on serendipity — and all of a sudden it’s like, Oh. That’s an interesting idea. I hardly ever read them. I’m just looking at the pictures. I read them when I first got them. Instead of [looking at images on her phone or computer screen] I like flipping through books. They’re my friends. They’re very familiar to me.

Describe your studio.

It’s the original cottage on the property [where she lives in Benzie County]. It’s six feet from the house. It’s ideal. People say how great it is to have a studio away from home. Well, I want my studio closer. When the mood strikes, I want to be able to easily waltz into the studio [18 feet x 20 feet]. I’m not one who wants a view in the studio. I love a basement studio if it’s well lit. I get easily distracted if there’s too many windows. I’m gawking at what’s going on out there. I do better if I have blinders on.

For a while now, you’ve worked on two, distinct thematic things: florals, and non-representational abstracts. Talk about both of those things.

The florals I love because they’re accessible for people. I can’t say they’re easy to make, but they’re fun to do. They’re joyful. I can play with color combinations. The abstracts: I love a challenge — that’s what has kept me interested in art for so many years. I’m never going arrive. You’re always going to get better. Abstracts are so challenging. I used to just start with an idea, and figure out where I was going to go in the middle [of the composition]. I still do that. But I’m learning that the design has to be great or no one is going to bother to see what you’re trying to say. If the piece of art isn’t interesting from across the room, then you’re not going to entice someone to come have a closer look. The design leads with [her abstracts], I’m finding. I come up with an idea while I’m working, and that helps me to finish. You work fast and furious to start. And, there’s a lot of thinking. The theme of the show of abstract paintings I’m doing [at Center Gallery August 5 – 11, in Glen Arbor, Michigan] is about hope. It’s called Wishing and Doing. I’d love to say I know exactly what [the paintings] are all going to be, but I’m exploring the theme [as she paints]. I have to be comfortable with a little bit of ambiguity.

Let’s go back to the florals. You said you love them because they’re accessible. What do you mean by that?

The floral paintings are easy to live with. There’s nothing mentally challenging about them. They’re pretty, and they’re uplifting. There aren’t many people who don’t love flowers.

You don’t strive for botanical accuracy in these painting.

No. The florals are more about color, color combinations. And then, as I paint them, each flower anthropomorphizes — they turn into individuals. They all have personalities. I find more people can look at flowers [than abstracts] because they’re not intimidated by a floral. Somebody looks at an abstract, and you’re asking something of them.

How do you flip back and forth between these two styles?

I don’t find it hard at all. The difference is the abstracts are more challenging, but the process is basically the same [for her floral paintings] — it’s all design. With florals, you know what your subject is going to look like; abstract, you don’t. You have to create a subject almost. It’s tough. My whole life, I’ve loved a challenge.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

What prompted the [recent] abstracts is Center Gallery approached me, and asked if I’d like to have a show of abstracts? Sometimes [the prompt is] external. I don’t pre-plan all that much. I let the process take charge.

Your floral paintings came out of a project you assigned yourself: the 100 Bouquets project.

The 100 Bouquets is now 200 Bouquets: I’m at [bouquet painting number] 137, I think. The project started from a business article I was reading. The question [posed in the article was]: What consistently sells the best? And, it was my florals. So, I thought, I’ll just do 100 bouquets, and see where it takes me. It was fabulous. I had a show of florals at [the GAAC in 2018], and it just blossomed from there. I like those little mini projects. If I’m going to do a project like that, the one thing I don’t do is keep it to myself. I make sure to tell people so I’ll follow through.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

Typically yes. Right now I’m not doing any florals because I’m getting ready for the [Center Gallery] abstract show. Typically, though, I’ll bounce around. You can feel yourself — I don’t know if it’s boredom — needing to switch it up a bit.

Your bouquets project is a good example of painting in a series. What happens, in terms of process, when you paint in a series?

Each painting informs the next. Before the florals, I did an abstract series called Taking The High Road, and it featured a lot of ladders. I worked on that for three or four years. At first it was a ladder in the background, and then there more ladders, and then there were lines, and circles. [In each of the paintings] you can see a progression [of the thematic idea]. You’ll bore yourself to death if you keep doing the same thing over and over. If you force yourself to keep with a theme, you’re going to innovate.

What’s your favorite tool?

My fingers. I’m tactile. I love the touch of things. It’s probably not real healthy — I don’t wear gloves, which is a bad practice. I usually remember to put Artguard on my hands. But I start with gloves, and then they’re off. I’m always softening or moving paint with my thumbs or fingers. I guess I never graduated from finger painting. The other thing is: the Procreate app on my iPad. After I’m done in my studio, I can have my iPad in the house, and play around with different ideas on [digital images of] paintings that are about three-quarters of the way done. I can audition 50 ideas in the span of 15 minutes. And, then, if some [inspiration] happens, the next day in the studio, I’m rarin’ to go. Not that you can’t do that [directly] on the work. You absolutely can. If I have no time constraints, that’s usually what I do. If I want to be really efficient with my time, Procreate is a god send. I find it really freeing to say, What would polka dots look like there? Oh, no! That was not a good idea.

Do you use a sketchbook?

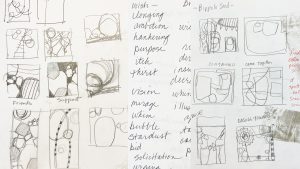

Yes. Before I start an abstract, I’ll do a lot of writing trying to nail down my thoughts about a subject. That will help lead the design. Sometimes, when I’m writing, I’ll do a bunch of thumbnail sketches. I have a million sketchbooks.

Why does working with one’s hands remain valuable, and vital to modern life?

I think, as a human, giving of yourself — whether it’s painting, cooking, quilting, furniture making, gardening — making things better in the world makes us feel better. I think it’s good for your mental health to step away, and create something that wasn’t there before.

We do use our hands a lot, but it’s mostly our thumbs.

I embrace technology. I love technology. It’s like anything: There’s good and bad to it. I do think it has had a negative impact, but it’s still relatively new technology — at least to me. So, we all have to figure out where it’s going to fit. It’s here. If it makes you uncomfortable, don’t use it. We all have to figure out where it fits for each of us — it’s a tool. I always have my tablet at the ready, I have a podcast going, or audio book. I need a lot of audio stimulation when I work. I embrace it, but there is definitely a negative aspect to too much.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

When I started doing the house portraits, I thought of them as a business. When I started [painting] watercolors, I entered a few shows, and had a few successes. I’m one who falls into things. And, if it feels OK, I’ll keep doing it. If it doesn’t, I won’t. I will always paint — can’t imagine not — until I die, or can’t possibly do it anymore. The challenge of [working with serious intent started with a question]: Can I do that? I think I can. I’ve had other jobs, and they’ve never engaged me like this. I love not having a boss, other than myself. It has engaged me completely. I’ve found my thing. We’re lucky. We don’t count on my income to eat, so I’m fortunate for that.

How does the income you derive from your practice influence how you feel about your success as an artist?

It’s a part of it. But it’s not the entire part of it. I’ll have good years, and bad years — a lot of it is out of your control. I’ve had years when, oh my god, everything I turn out sells. And then I’ll have a year where it’s like, Hello??? Anybody out there?

Let’s talk about social media. You have an email newsletter, you publish instructional videos on your Facebook page, you use Instagram.

The newsletter — which I’ve ignored for too long — it used to be when I sent out the newsletter, it would always result in a sale, so how dumb is it not to do it? Writing is hard for me. It takes a lot of time and effort to do the newsletter, so I’ve kind of let it go. I might bring it back. I don’t know. I like to share ideas with other artists, so if I come across something [exciting], I’ll share it through Instagram or on Facebook. They’re two, distinct and different audiences. People I actually know follow me on Facebook. People I don’t know follow me on Instagram, and I have a larger following on Instagram. I used to love Instagram, but they’ve shifted to a lot of [moving content on video], and it’s not as relaxing for me to scroll through there anymore.

What’s the role of social media in your practice?

It’s a record-keeping thing. If I wonder when I painted something, I can scroll through Instagram quicker than I can [rooting through] my records. There is connection. I’ll get notes from people, other than local people. It’s about accountability. It shows I’m a working artist. I putting work out. It’s a bit of professionalism these days. Sharing is part of it. Do you have to? No. But I think a lot of people expect it. It attracts a younger audience, too.

What’s the influence of social media on the work you make?

I don’t think there’s a ton, except you can scroll through, and see what other artists are making. That’s fun to see. It’s like going to a mini museum. It provides inspiration. You’ll scroll by and see a color combination, and think, I want to try that. Not copying someone else’s work, but inspiration.

What do you believe is the creative practitioner’s role in the world?

That’s a big question. We try to connect with people on an emotional level that is weirdly personal, and at the same time, universal. Artists can bring respite, uplift, inspire, and motivate change. Creatives can make connections where there previously were none, and bring a richness and depth to an experience. We can illustrate a problem that may bring a person to a new understanding or perspective. I also think we encourage non-artists to try their hand at creating, at least I do.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

One of the reasons I’m limiting my news consumption [these days] is I’m trying to do this show about hope. I’m a Pollyanna. I try to look on the bright side. When I get too far down, I think: There’s a lot of fabulous things going on now that no one knows about. It’s not being reported. That’s the stuff I cling on to. I think just living influences my work. All of a sudden you’re doing something completely unrelated, and then something happens, and, oh my god: That’s a little spark of an idea. As far as my painting goes, I’m trying to keep the negative parts of the world out. I’m looking for all the good stuff, whether I come across it or just dream it up. I angst in my sketchbook. If I’m mad or sad about something, my sketchbook gets all that. It’s my release, and then I can go and do my happy thing.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

We’ve never lived in a tourist destination before. We were always the tourists coming up to see my mom and dad [in Benzie County]. What I found I love up here is winter. After Christmas, there’s nobody up here, and you can walk down the middle of M-22 and not see another car or soul. I love that solitude, and the quiet. Winter is an important time to get new work done. I can really immerse myself without distraction. I don’t think [however] the sense of place is [visible] in my work.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

No. My mom was a quilter — hobbyist. My dad a woodworker —hobbyist. I didn’t know any artists growing up. I stumbled into it.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

So many people. Starting out, it was pretty much [a] self-taught [experience]. Once I got to watercolor, then all those instructors at Birmingham Bloomfield got me going there. And then, I started in acrylic, and started taking workshops. Brian Atyeo was the first acrylic instructor I had. Robert Burridge, I took a workshop from him. I really liked the way he attacked [his work], and I still do that. The first strokes of my work are fast and furious. My art friends are all influential as well.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

I have a critique group up here that’s helpful, and it’s made up of local artists. We meet one a month. I have a critique group from downstate. They’re so kind. They include me every once in a while in a ZOOM meeting. I find their advice invaluable. If I’m stuck, I know I could send an image to that group, and they would help me in a heartbeat. I’m also part of an [online] group called Art2Life. They have a feedback section. I don’t know these people, but I get excellent advice.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

Robert Burridge said, and it made me laugh, that unseen is unsold. Letting work sit in the studio isn’t doing it any good. I haven’t done that many solo shows. [Getting ready for an exhibition] almost feels like you have all these little pieces of an overarching idea. I’m enjoying trying to figure out all [the Center Gallery paintings] are going to fit together. I have six or seven of these small, 6” x 6” paintings that I’m enamored of, but I know they’re not going to fit [in the Center Gallery show]. There’s also the pressure of the deadlines.

How do you feed, and nurture your creativity?

I walk most days in Sleeping Bear [Dunes National Lakeshore]. It’s about 100 feet [out her front door]. I do a short walk [with Major, her 13-year-old dog]. Then I meet fellow artists, and walk in the park on Thursdays. With the artist friends, there’s always art talk that happens. It’s half art, half talk about family, and general conversation. My solo walks are the ones that really feed me. It’s almost meditative. I like to go early in the morning. Even when it’s crowded, I rarely run into anybody. If you get out around 7-ish, there’s nobody out. After 8 am, it’s really people-y.

What drives your impulse to make?

Wouldn’t that be interesting to know what it is. Some of it is: I think I can. What would happen if ? Something pops in your head, and that’s an interesting idea. I’m impulsive, and I jump in, but without a ton of thought sometimes. With art, though, I’m not going to get into too much trouble. It’s a good place to be impulsive. I really do need to make things, and I wish I knew why. It’s just innate. I’m unhappy if I’m away from the studio too long. But once I walk into the studio, it’s: Ahhhhh. This is where I needed to be.

Read more about Lauren Everett Finn here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.