Antrim County painter Wendy McWhorter, 68, is a late bloomer, self-described. But after retiring in 2013 she blossomed — a verb that applies to her creative practice, and her subject matter. Wendy is passionate about flowers. They meet so many needs: color, shape, their brightening presence in the landscape and the front yard. But it’s not all florals. Northern Michigan’s landscape speaks to her. Loudly. And, year-round. Once blossomed, this painter does not seem capable of wilting.

This interview was conducted in April 2024 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Wendy McWhorter

What is the medium in which you work.

Oils. Occasionally I do watercolor when I can’t take oils; but oils are my preferred medium.

Why?

Because I love the saturation of the colors, and — as one instructor said — the “juicy-ness” of the medium.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

Yes I did. “Formal,” back then, would be instruction in abstract art. All the professors in the the 70s were teaching abstract. My first two years were at Northwestern Michigan College [1973-75], and the instructor I got the most out of was Jack Ozegovic, the printmaker. I really enjoyed printmaking, and thought that that was what I was going to do. He encouraged me, so I went to Indiana University for a year [1975-76]. Although I really liked printmaking, I didn’t think I could make a living as an artist. I changed my journey, and went on to become an art teacher. [Before that, however] I went to Michigan State University to get a degree in advertising — all my credentials just seemed to fit that. I graduated from MSU in 1979. I [worked in advertising] until 1985 at the Traverse City Record-Eagle. I enrolled at Eastern Michigan University and got my certification in art ed, and started teaching in 1988. The only time I was able to do my own art was in the summertime, and that wasn’t conducive to a good practice. I retired in 2013, and became more dedicated to painting. I started painting every day.

When you were studying printmaking, you said you didn’t feel like you could earn a living in visual art. Why?

I didn’t have the dedication to push myself to create a body of work back then. At 21 years of age, I didn’t have the maturity to know that. I didn’t have the tenacity. I didn’t have the hunger to do it. When you’re young, you have to make a living. I didn’t see how I could do that unless I had a 9-to-5 job; but then I would not have the energy to do art at the same time. I didn’t want to be a starving artist. I love New York City now, as an adult; but as a 21-year-old, it would have eaten me up. I was a late bloomer, a real late bloomer. I didn’t realize the tenacity and hunger part of being an artist until I was 58.

Is New York City the place you imagined one went to to seriously practice visual art?

Yes. That was my experience with everything I’d read about being an artist. The internet has changed that [perception]. You can live in rural Michigan, and if you want to, you can be shown in New York City. Or, you don’t have to be in a gallery anymore. People can see your artwork on Instagram, and bypass the whole gallery scene — if that’s what you want. [Wendy uses Instagram and Facebook in her practice.]

For me, being a regional artist, the people who are interested in my art are local to this area. My interest [subject] is in the geography, the topography of the northwest area — Leelanau County, Antrim County, Old Mission, Charlevoix, and Petoskey. When people are looking at art, they want to see something that reflects the beauty they see, and why they’re there. Artwork in their home, if it’s of a place they’re familiar with, that they have a memory of, that’s one of the reasons why they buy my work.

Describe your studio.

It is a 10 ft. x 10 ft. space I carved out of the lower level [of her home]. I had a wall put up, with a barn door in it. I have two light sources. I have a nice, big window, and door with a window. I can walk out from it [under the upper patio], so I have a sheltered place where I can work outside. That’s nice. When people want to come see my work, they don’t have to come into the house. We can walk right to my studio.

As we’re talking, you’re preparing work for Bloom, an exhibit of floral paintings at the Botanic Gardens/Historic Barns Park in Traverse City, Michigan. Bloom is a continuation of work you did last year for another exhibition, Lost and Found Gardens — exhibited at Center Gallery in Glen Arbor, Michigan. In Lost and Found Gardens, you imagined the flowers planted by early settlers at Port Oneida. How did you research the flora that existed in Port Oneida?

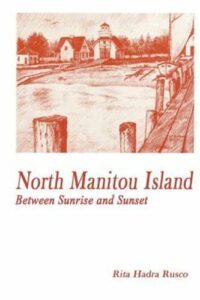

I went to the Leelanau Historical Museum, and did some research there. I also looked online, and read a book by a woman [Rita Hadra Rusco] who lived on North Manitou Island for a long time. What I discovered was that a lot of lilacs were planted, wild roses, and when the boats would come to Glen Haven and different ports along the way, they’d sell bulbs, so people had daffodils, tulips. The most common native flowers were Coneflowers and Black-eyed Susans.

How do you feel about people wanting to come visit you at your studio?

It’s by appointment. I don’t have a sign up. I’ve never had a drop-in. I only got the studio two years ago, and it was still quite clean then. Now, I’d have to stop everything I’m doing if someone wants to come visit, and clean up. I don’t mind. It’s always interesting. Visitors might have come to look at one painting, then see something else they like. That’s the good thing about a studio visit: They can see all the work in person.

What themes are the focus of your work?

Incorporating nature — flowers and gardens and blooming trees — with the vernacular architecture of the area — the farmhouses, the barns. I like to put the two together. One is geometric, and one is organic. If it makes sense, I put the flowers in the foreground. Sometimes I focus on the farm; sometimes I focus on the flowers.

It sounds like you don’t take dictation from the scene. You give yourself the latitude and the freedom to arrange the components as you want them to appear in the composition.

Exactly. I take artistic license. The series I did last summer, there weren’t any flower there [when she was painting]. Through my research, I put them in.

What’s your favorite tool?

It has got to be the paint brush. The larger the paintbrush the better. That’s a life-long struggle for artists, to use a larger brush so you have a looser painting; and not using a smaller brush that will get you into the tightness of the details.

Do you use a sketchbook, or a work journal?

In my studio I have a vision board with a lot of photographs on it, of what I want to do. When I’m out in the field, I’ll take out my viewfinder, zero in on what I want to paint, do a rough sketch, and figure out my colors.

Explain the vision board.

It’s a bulletin board. I have it divided up into paintings I’m focused on [if she’s preparing for a show]; the other is work that I submit to exhibitions and galleries. I divide it up among the venues that I have. The Torch Blue Gallery [in Alden] want scenes of Torch Lake. [Another gallery in] Charlevoix wants paintings of sail boats, still lives. I have photographs of gardens, photographs of interesting barns and homes I like. I use [the vision board] to come up with my ideas. It’s there for me to look at all the time. I have on it a calendar of what I want to accomplish. I also have different pictures of artists’ whose work I like.

Earlier in our conversation you said that you can live in Northern Michigan, and have a shot at earning a living, because of social media. It allows people farther away to see your work. Is there any other role that social media plays in your work?

You get instant feedback from it. It’s a way to connect with people. They follow you. They make comments. Maybe a couple months later, they decide they really like a painting they’ve been looking at, and they buy it. I really appreciated it during COVID. It was a way to interact with people and market myself. There were no gallery shows. It created a new venue for people to look at art.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

As an educator, I had that nailed down. As a visual artist, I’m still formulating [an answer]. I’m not a social justice artist. My artwork does not resonate with different things going on in the world. I appreciate artists [whose work falls under the social justice umbrella]; their role is clearly defined: They’re shining a light on what’s happening in our world, whether it’s war, climate change, racial disparity. Artists who are speaking to those issues are making a change. My artwork is simply for someone who wants to appreciate my vision of what I see out there in the world — paintings of the environment in Northwest Michigan, the hills, the lakes, the dunes. Appreciating nature. It’s ephemeral. It comes and goes. A record of what was, and let’s not forget it.

People have told you they purchase your paintings as a way to have a reminder of what they love. Is the role you play in the world that of creating a touchstone for people?

It’s a comfort. For three years in a row, [a client] who is a jewelry designer who lives in New York City, whose family has a cottage on Lake Michigan [in Leelanau County] has bought a painting from me each summer at the [GAAC’s] Paint Out. She said that these paintings, in her home in Brooklyn, remind her of her summer memories. And, I like to think of that — that I’ve got paintings in Brooklyn, which is a juxtaposition from a very busy area to a very relaxing memory of summer.

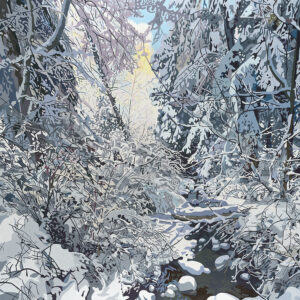

It’s one of the reasons why I moved back here from our little stint in Florida. Florida is flat. It’s extremely humid. It’s not very varied in topography. I have been up here, this past fall, for 50 years: going to NMC; my parents had a place in Glen Arbor; moving here after MSU. I’ve decided this is where home is. I’m much more inspired to paint here than anywhere else. It’s a connection. It’s a familiarity. But there’s also the unknown. In February, there was a really nice day, and I was going to paint near these orchards I always go to — I wanted to see what it was like to paint in the winter when there wasn’t any foliage. I was looking in my rearview mirror, and said, Wow. I’ve never seen that view before. So, I turned around. It was a farm. It looked like a Wolf Kahn painting, like a Grant Wood painting. With the bay, and the farm, and the fields: It was a perfect painting. And it’s a place I drive by every week; but because I looked in my rear-view mirror, I saw it differently. There are surprises every day. This is what I want to paint.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

No I didn’t. However, having proximity to the Flint Institute of Arts was huge inspiration for me [Wendy grew up about 12 miles south of Flint]. I was lucky enough that my father appreciated culture. He’d drop me off at the FIA on Saturdays to take classes, so that’s what informed my early art practice — and then going into the FIA’s fabulous galleries. It’s a world-class museum. When I was teaching [at a Lansing, Michigan magnet school in 2010], I took students there.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I’ve always loved Wolf Kahn’s work. In 2004 I was going to a workshop in New Hampshire, and I went through Vermont, where there was a gallery that had his work. To see it large and up close was a fabulous feeling. This is exactly the kind of painting I can do in Northern Michigan. I like how simple the shapes are. That was a beginning for me in my thinking about landscape painting. I also like the work of Fairfield Porter. Similar reasons. Subject matter is what drew me to those two: the geography of places that are similar to here, water, hills, dunes, forests. Also: Nell Blaine. I liked her story. She was an artist who was struck by polio in 1932. They told her she’d never paint again, and she just fought through it. Eventually, she was in a wheelchair; but she wheeled herself outside, and continued to be a plein air painter. When she could not do that, she brought the outdoors indoors. She had flowers brought into her home, she painted those, and incorporated that with what was outside. That struck me. Somebody who had a lot of obstacles and worked through it.

You said you’d had such a profound experience looking directly at Wolf Kahn’s work — as opposed to looking at it on a screen. Talk about the importance of having people look at your work, directly.

It’s important to look at things directly because the screen does not show the work accurately. It does not show brush strokes — if you’re an oil painter it’s important for viewers to see how the artist has created with the brush. And size. When you’re looking at something on the screen, even though it might say something is 36” x 48”, you just can’t imagine that until you can back up and sit with it. That’s why I like benches in museums.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

I have a good friend who has bought many of my paintings. She has a good eye for what’s missing. And, she’ll tell me. That began a couple years ago. When I’m struggling with something, I send it to her, and she pinpoints it. She’s a non-artist, which, to me, is very helpful. She’s a true critic. She’s not kind. She’s objective, too.

You’ve been doing a lot of exhibiting in the last few years. Talk about the importance of exhibiting in your practice.

It’s important. It gives me an impetus for creating series of paintings. And, series of paintings let you explore a subject. The other reason is it gives you an opportunity to interact with people, like at an opening. For someone to say, Where is this at? It looks familiar; I can explain where I painted it, otherwise, you don’t interact in person. Some galleries have a following, and those people are looking for a particular kind of art, so that becomes an excellent place for the artist and the collector to meet.

You raise the not-so-glamorous issue of the practicing artist’s need to do R+D: finding your niche, where your work is a good fit. Not everybody is going to come to an exhibition because you’ve put something up on the wall. That’s the business part of having a creative practice.

The show I’m going to have [in the Botanic Gardens], they have a following. So, I did a lot of press releases. I also targeted a lot of local garden clubs. You have to do your own marketing. It takes time. But I’ve created a list, which I can plug in for future shows.

You don’t strike me as someone who paints what you think people might like to see.

Right. I paint what I like to paint. That’s why I rarely do commissions. Most of the time, that meets with what other people are interested in. I’m not commercially oriented. I’m not making a living on my art. I’m appreciative of what it takes to make a living. That’s a 24/7 job. I’m not a working artist. I’m practicing; but it’s not my bread and butter.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

I look at a lot of artists’ books. It’s amazing how expensive they are. So, luckily, with MEL Cat, I’ll go to my local library and ask them to get it for me. If I can, I find something at an estate sale. I do a lot of that. And, I went to New York City for three days. I went to the Metropolitan, to the Neuw Galerie. A month ago, I went to the Birmingham Art Center. I go to local art openings to see what other artists are doing. I have a network of artists who I talk to.

What drives your impulse to make?

I enjoy going out and painting plein air: Being outside is a big drive. I like to be outdoors as much as I can; but when the weather’s not great, I like to be in my studio. It my happy place. It’s a state of being. It’s mentally a good place.

Read more about Wendy McWhorter here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.