Creativity Q+A with Mike Cotter

Blankets. Pieces of mirror. A chair that isn’t a chair. Traverse City artist Mike Cotter, 79, has spent a long time thinking about low materials as high art. He went back to art school after moving permanently to Traverse City in 2008, and reignited a dormant studio practice that got sidelined. This is what he thinks about that — including some thoughts from Andy Warhol and Piet Mondrian.

This interview was conducted in March 2024 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Mike Cotter in his studio.

Describe the medium in which you work. What is your work?

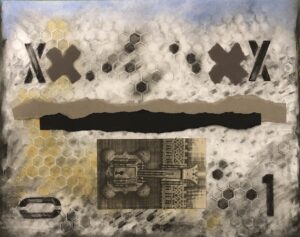

Multimedia at this time. Probably wall-oriented assemblage. Collages and drawing.

When you say “wall-oriented assemblage,” do you mean 2D?

Some people would say it’s 2D — you can’t walk behind it. But there’s texture on the surface, something sticking out from it.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

Throughout my career I’ve always been fascinated and inspired by non-art materials.

For instance?

At one time I was into linoleum a lot. Another time I used camp blankets stretched over frames, then went back in a worked in mirrors and rope and string on those pieces.

What is about these kinds of materials that interests you?

I like the idea of making what was called, in art school, “high art” from non-traditional materials. Some people might say that’s more like crafting; but I don’t see it as crafting.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

I got a BFA in 1968 from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in painting. I got an MFA in 1970 from Yale University in painting, but I did mostly sculpture; but it wasn’t traditional sculpture. A lot of pieces were furniture-oriented; but they couldn’t be used as furniture.

When you got your MFA, did you plunge into a studio practice? Or, other?

That was 1970: Let’s tune in and drop out. I went from New Haven to San Francisco. When I first moved there I had a studio space in the living room of a flat that I used. I was in some shows, but not a lot. In 1973 I moved to New York, and I did have a loft in New York. Then I moved to Brooklyn. I was doing work that was more like what’s in the [GAAC’s] HAPPY show [January 12 – March 21, 2024].

Was there a point at which you felt as though you needed to get a “regular job”?

In California, it only cost $28-a-month to live in the commune, so I didn’t need a lot of money; but I was working as a pizza delivery guy. When I moved to New York, I did get a job with the Department of Social Services. I guided senior citizens with their art in a couple different senior centers in Brooklyn. When I left New York in 1977 I’d just gotten accepted to be represented by the Holly Solomon Gallery in New York. That was a big deal; but I’d made the decision to move back to Chicago, so for 30 years I dropped out of [his art practice]. When I first moved back to Chicago, I had a studio for a year. I did one more piece, a drawing that got into the Chicago and Vicinity show at the Art Institute. I think Jasper Johns was the juror of the show, and I thought that was pretty cool. For 30 years, I worked in the corporate world — I had a corporate travel agency. When I retired, my biggest client hired me to be their director of operations, and I did that for 10 years. I always wanted to do more art, rather than buy art, so I went back to Northwestern Michigan College [in Traverse City, Michigan] for two years, and took drawing classes [2009-2010].

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner? What did you carry from school into your practice?

I think it honed and trained and educated the artist’s eye. I used all kinds of things I learned. They gave you a tool box to use.

Describe your studio space.

It’s a room in the house, on the lower level, and I share it with Irene [his wife, a fellow student at the School of the Art Institute ,who he met in 1964]. We don’t have conflicts as far as who’s using it at what time. We don’t ever work at the same time. We respect one another’s need for creative space. There’s one window, and it looks out onto a window well. So, there’s light.

How do you like having a studio in your home — as opposed to having a place you need to travel to?

It’s fine. It’s a space where you can close the door. You don’t have to neaten-it-up. At times, when you’re at home, and you’re working and want to give it a break — and think, What am I going to make for dinner — it can be distracting. You have your library, your garden, cooking. But if I go in and close the door, I’m pretty in-the-moment with the work.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Sometimes I tend to be more attracted to something that’s not non-representational, but are objects that are abstracted from the real world — like when I did all the furniture pieces that were not furniture. Some people look at my work and say, Oh, it’s all so different; but I see connections between things.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

Well lately, it’s [the GAAC’s] themed shows. Again, I think it goes back to interest in materials. [Speaking hypothetically], I love how these hooks in the screen door work. I’m going to do something that’s related to that. To not just stay with the thing as it is. Piet Mondrian, wrote, and I love this quote: The interior of things shows through the surface. Thus as we look at the surface, the inner image is formed in our soul. It is this inner image that should be represented. For the natural surface of things is beautiful; but the imitation of it is without life. Things give us everything; but the representation of things gives us nothing. I like other artists’ work that has soul to it. It has to evoke a feeling in your soul.

So, springboard off of that: If you come across an object you like, is it accurate to say it could be the starting place for looking for its soul? Versus just representing the physical form of the object?

Or, give it a soul. I look at a fellow Art Institute guy, Claes Oldenburg, and the objects he made — the lipsticks, the hamburger, the clothespin. It wasn’t just a clothespin. There was other meaning to that.

What’s your favorite tool?

My eyes. If you don’t have the eye to see, to create, you don’t have anything. But more traditionally, I would say vine charcoal. I love the grittiness, and the softness, and being able to manipulate it with your hand or an eraser.

Do you use a sketchbook?

As an art student, I was joined at the hip with my sketchbook, and filled many of them. Write notes, put leaves in them. Now, I use the sketchbook in the studio to work out ideas for a final piece.

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

Because I like doing it, and I’m pretty good at it. It’s probably generational — as opposed to a lot of work being made now.

Talk more about what you mean by “generational”?

I like touching and reading a book rather than an E-book. There’s something about smelling the book and touching the pages and leafing back and forth in a book as opposed to [reading from] a flat screen with a light behind it. That relates to doing work by hand. Like I said, there’s something about vine charcoal: There’s something about the texture, and the feel, and getting your hands dirty. In all of that, it adds to the soul of a piece.

Why does working with our hands remain valuable and vital to modern life? Or, not?

I think it slows you down to be more human.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

What role does social media play in your practice?

Not much.

What’s its influence on the work you make?

Very little. The only time I’m connected to social media is through what a gallery or museum would do to promote a show I’m in.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

The artist acts as vehicle to viewers, to open up a dialogue between people. Say two people walk into [a gallery] and look at one of my pieces. They may not know one another; but they could be standing next to one another and a comment might start them discussing it. Anything that opens up a dialogue among people is a good thing. I think there’s very little dialogue between people [today]. If you’re able to create any, that’s a good thing. Just look at today: You don’t have telephone calls, you have texts. That’s not bad; but it’s all one way.

There’s a lack of direct engagement with another human being.

Right. You can think it. And you’re not confronted.

What part or parts of the world find their way into your work?

It can be anything from color to cobblestones. Andy Warhol said, The world fascinates me. I have that quote up on my studio wall. I’m interested in most all of it.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your work?

Living here gives my brain room to breathe — as opposed to suburban Chicago, or the city of Chicago. Some people can work in chaos. I wouldn’t say my studio space is neat; but if I don’t have things where they should be, my brain won’t work properly. The environment here — it’s so physically beautiful. I could see where it’d be very easy to not do any work.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

My father was a very creative person. In the town where I grew up [Evanston, Illinois], there was only one art supply store, and it was run by this artist — Walter Burt Adams. He was kind of a Hopper-esque Regionalist. In fact, I own two of his paintings now. His day job was running an art supply store; but he’d go out and do plein air painting all around the city of Evanston [Illinois]. He was very rough, and curmudgeonly. He didn’t have phone in the store. He didn’t have a car. He was unique. [And] in my mind, he was a serious artist.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I would say, number one, would be my teacher and mentor at the School of the Art Institute: Ray Yoshida. Ray was the key influencer of the Chicago Imagists. They all kneeled before him: the Hairy Who, Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson. He was an amazing artist himself. All of the stuff from his house and studio is relocated into the [John Michael Kohler Arts Center]. Ray was probably the most influential as it regards how I would look at the world. In the classical sense, two artists [also influenced Mike]: Henri Matisse, and Marsden Hartley. When I was at Yale, the person who had the most influence on me was Lucas Samaras [who Mike invited to speak at Yale]. We just clicked. At one time, he did this mirrored room [now at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo]. You walk in, and everything is covered in mirrors — the chairs, the furniture. At times, I would go and visit his apartment in New York.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My wife, Irene [they have been married 40 years]. I still have a close friend from the Art Institute, Gloria Brush, who was the head of the art school at the University of Minnesota at Duluth. She’s a photographer. Someone I met in California, Ford Wheeler , and he’s a Hollywood production designer. Locally, I would say Howard and Nancy Crisp.

You’ve just named five people. What do they have in common? Why do you turn to them for feedback?

First of all, I like what they do as artists. If you don’t have respect for someone else’s work, you can’t expect them to tell you anything of value about your work. You trust them because they’re friends.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

Does the validation come from the fact that an institution says, This guy made the grade.

You don’t have to sell it. It would be nice if it sold; but again, it’s about people coming in and having a dialogue about the work. The artist doesn’t always hear it.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

It goes back to the artist’s eye. You have to not only see your surroundings, but look at them. There was this woman north of Chicago who ran this mid-century modern gallery, old stuff she sold from the 1950s and 60s. When I’d visit the gallery, we’d talk about art. She said, To have an artist’s eye is a gift and a curse at the same time.

An artist’s “eye” doesn’t allow your brain to say, Oh! There’s a tree! It says, Oh! There’s a tree. And now I’m going to look at the pattern in the bark, and the colors and values. It’s a full-body experience.

It can be exhausting; but I’m always so grateful I’m an artist. I can’t imagine not. It’s a gift.

What drives your impulse to make?

Whether it’s working to be in a show or exhibit, it’s innate. It’s there. You want to fulfill that desire to create. I can’t imagine not doing it. It’s not just my work. It’s a way of being. Whether it’s making a beautiful meal for someone, or knowing how you’re going to plant a garden. There are many ways that an artist lives. A true artist is not in the studio alone. It’s not just what they make, their work, and then the rest of their life is not creative.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.