Leelanau County, Michigan, artist Cynthia Marks, 71, has been “making art for 50+ years, a startling and comforting thought,” she said. “I am consumed by using clay to conceptualize most any thought in a form or surface, generally drawing from my everyday life, art history, and nature.” Cynthia hand-builds vessels and pots from terra cotta and white stoneware clay, into which she carves, stamps, and draws to create highly decorative surfaces; “experimenting with different clay bodies and always searching for that huge, new thought.” And it all begins with a coil of clay. This interview was conducted in January 2023 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured left: Cynthia Marks

What is your process for making vessels?

I build using coils. I roll coils. I score and slip in-between. I often use a template to get the form. If it’s a large piece, I always use a template that I’ve made out of tag board.

The scoring of the coils is to create two, rough surfaces. You lightly score the coil, then score the preceding coil, which is affixed to a base. That allows you to get a better bond. Some potters will leave their coils showing on the outside; I do not. I’m quick at rolling coils. I find that when I build with slabs, I spend more time getting rid of the slab mark, and sometimes they come back when subjected to heat. I use coils to build about 90 percent of the time. Once in a while I’ll get on a jag and throw but I’ve tried throwing vases and doing my surface technique that I’ve adapted or invented, but people prefer hand building — as far as selling my work in galleries goes.

Does hand building give you different kinds of freedoms that throwing does not?

Yes. And, I’m better at it. I lived in an area, most of my life, where there were many potters. Goshen College was right up the road, and at the helm was Marvin Bartel, and no one could throw better than Marvin and all of his students. And some of them, especially big brawny men, stayed in the area. In the other direction, to the west, we had Bill Kremer at Notre Dame, and he had a following and a flock that stayed in South Bend [Indiana]. So there were a lot of these young, brawny men who could throw. And even when I was young, I couldn’t throw as well as they did, and I didn’t have time to perfect the skill because I was teaching [high school art] full-time and raising a family.

Were you trying to differentiate yourself from the herd of throwers?

I taught throwing for a long, long time. I taught it every semester. I had six wheels. But for my own personal work I felt more satisfied when I hand built. You can experiment more.

[NOTE: Cynthia taught visual art in the Indiana Public School system from 1975 – 2008.]

Why do you like working in clay?

I came to clay as a means of expression because it was what the schools [she attended] could afford to buy. My degree is actually in jewelry design and metal smithing. But I had also taken a good amount of hours in ceramics in undergrad, and I liked it. I was good at it, so I did it.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

I wouldn’t be where I am today. I always say it’s the power of an IU degree.

[NOTE: Cynthia attended Indiana University/Bloomington from 1970-74, receiving a Bachelors of Science/Education; and a Masters of Science/Education from Indiana University, 1976-79.]

People say, Oh, you’re so talented. And I say, No. I’m highly educated. I was so fortunate to work with and be mentored by famous people. Alma Eikerman, the head of metal smithing and jewelry design at IU, was my friend. We had a long relationship, long after I graduated. And the same with Karl Martz and John Goodheart in ceramics. They were huge in the field. I didn’t know it until later, but for a public university their art program was sixth in the nation. For a little girl from Mishawaka [Indiana], who was first generation [college student in her immediate family], it was a pretty big deal.

Describe your studio/work space.

My work space is probably why I live here. We [husband David] built our little cottage in 2015. It was just to be a weekend place. When we got tired of going back and forth after four years, I said that I can’t live here without a studio. There’s no way. So, over the course of a week, my husband and my son-in-law’s father framed out half of our basement — about 600 square feet, but it’s more than adequate. It has an easement window, so birds hop along the edge, and once in a while a frog or snake gets down in there. I go down there, and I just smile. I used to laugh. Before we remodeled, the most expensive thing in the house was my kiln. My husband insisted I couldn’t buy a used one. So I bought a brand new Skutt. Great big, beautiful Skutt.

Why did your husband insist on a brand new kiln?

He likes me to be happy. I wasn’t keen on this idea of moving here. I thought of myself as a city girl. His grandparents had a cherry farm in Arcadia, so he spent his whole life coming here every summer, and then we started vacationing [in Leelanau County].

How does your studio facilitate your work?

I think artists are very much into their tools and equipment, at least I am. I’m also old school: I have to have a book shelf because I still use books. I have a big bench and wedging board. I have an array of glazes. I have everything I need, and more. It’s the biggest room in our house.

Tell me about the books.

I have jewelry books. I have animal books. I have pattern books. I have textile history books. I tend to not look at other people’s pots. Marvin Bartel taught me that. He advised his students to look at jewelry, painting, sculpture, art history. We can borrow; we don’t need to copy someone else’s pots. And, I took that to heart. I had an extensive library when I was growing up. We used to laugh about going to the Church of Borders on Sunday mornings. I used to buy the newest, latest [ideas], boxes of books to take to my classroom, and I kept a lot of them when we moved here.

Many people use the internet in the way you use books.

I do that, too. I’ve been on the internet all week trying to get my thoughts together for my next show [a group show proposed for 2024] — as well as making my work for my spring gallery orders.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

I always start with form. It’s like putting lipstick on a pig if you put a beautiful design on a sloppy pot. There are rules. At least there were rules for the people I studied with. A pot’s top and foot should differ, they should not be the same. The fullest point should not be the top or the base. A pot needs a shoulder. A pot needs a neck. To have some interest, it should look like there’s a life inside trying to get out.

Your pots are very decorative. Talk about your approach to surface design.

I do brighter colors in the winter. When it’s cold, I want warm. And I tend to do cooler, more landscape-y colors in the summer. We do some hiking and foraging for mushrooms, and I love the palette in the spring. I generally make about 12 pots at a time. I start with pinch pots, in varied sizes, then I coil them shut. And then I have spout day. I might make 25 spouts. I do all kinds of crazy things. I roll them up and down the woodwork in my studio, or the metal shelves. I do things to get striations and texture. I’ll let them harden, and then go back down and try to figure which spout goes with which pot. And then I’ll decide: Do they need a handle? Or a little cape [IMAGE?] on the top. I do a lot of trial-and-error, and a lot of experimenting. I don’t have completed drawings of each pot before I begin.

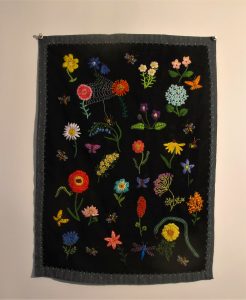

Talk about all the flowers and vegetation that you add to the surfaces of your pots.

Our whole yard is flowers. We don’t have grass. And, I’ve gardened all my life. I suppose, if we’re talking about our histories and our pasts, and our stories, and our lives, spending time in my grandmother’s garden was certainly why I do what I do. I spend a couple hours in my garden two or three days a week, and then I go down to my studio.

I might do five or six pieces from nature, and five or six pieces from art history. Those are my two loves. That’s what I’m interested in. If someone says to me, Would you make me a pot with a picture of my dog on it?, chances are good I would say, I love that you love your dog, but there are other people who can do that better.

If you focus on art history, what themes or visual references are you pulling from that for your own work?

It isn’t usually themes as much as it is individuals. I have certain artists I’ve always been drawn to. I’ve been into Paul Klee since I was 10-years-old. I’ve always loved Kandinsky, and Caravaggio. Right now, I’m sort of learning toward American artists for this next body of work. I’ve spent all my time in the past 30 or 40 years worrying about the Europeans or the Africans. We’re planning on taking a trip to the Hudson Valley. We had a great Wyeth experience a couple of years ago, and we’ve been trying to get to Chadds Ford.

What’s your favorite tool?

An expired card from the subway in London. I brought it back when I went to the Chelsea Flower Show [in 2019]. That’s my smoothing device. I have a whole bowl of different expired credit cards, and driver’s licenses, and ID. They are all different. They come in different weights and grades, and some work better for some things than others. I use a clay body that has a fair amount of grog in it. When I rake that credit card across the body of the pot, it creates a mark. I sometimes think I’m a frustrated printmaker because I love mark making, texture. Maybe that’s why I’m not so much into throwing [pots on the wheel]. I don’t like things that are smooth.

I also paddle a lot. That comes my background in metalsmithing: the hammer against the metal against the stake, which stretches it. And so, I stretch the clay. I build with a coil of clay that is the size of my index finger. As I paddle I’m stretching the clay, thinner and thinner, higher and higher. I like the sound. It’s just fun.

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

I’ve never not. I’ve said to my family — I have macular degeneration, but it’s under control — when and if I go blind, and I can’t make work, then I can’t see much point in being. I’ve never done anything but make art. What I like about being an artist and using my hands is the solitariness of it. I’m never bored.

Why do you think hand work needs to remain a vital part of human life?

My daughter and I talk about this all the time. I think about the satisfaction we get from creating. I figured out one time I saw 20,000 kids over 35 year, and so many of them are still using the [hand-making] skills I taught them. It’s a pleasure to them. It balances their families. I look at people, and I don’t know what they do all day — if you don’t sew or knit or make art or go out and take photographs. I can’t imagine how you fill your days if you’re not creating.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

I was 10-years-old. In Indiana, in the fourth grade you study Indiana history, and I made a Native American sculpture on a bottle of dish washing soap [with modeling clay, and papier mache]. I can see her today. I just always thought I could keep doing it. A lot of it might have been the teachers, who were so encouraging. But I never wanted to do anything else.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I have a network of former students I stay in touch with through Instagram and Facebook. I like [for friends and family] to see the old gal is still doing the work. Walking the walk. I don’t sell or have a website. [Conversely] I do a lot of gallery visits through social media. I use it that way.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

As an educator, I was constantly pointing out the role of art in our lives, and how much nicer it would be to have a spoon that feels good in your hand, or have a cup that’s made by an individual.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your practice, and what you make?

I don’t think it does. I’ve always said, I try to optimistically bloom where I’m planted. Wherever I am, I try to do my best, and help others, and make art. I really did not want to live here. It’s too rural for me. I do [however] like the quiet, and I like the light. I like the colors here. I’m not a big beach person. But my flowers do better here [than in Indiana].

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who was a serious, creative practitioner?

My high school art teacher. Her name was Rosa Weikel who taught at Mishawaka High School. She was a wonderful watercolor painter, and sold work in a little framing store downtown. That said to me she must be good! She painted very traditional themes. She was very quiet, and stern, and tiny. And, she paid a lot of attention to me.

Who has had the greatest, lasting influence on your work and practice?

Alma Eikermann. She was the head of metals at I.U. A phenomenal artist and teacher. She brought the idea of Danish holloware to America. She was a really colorful woman. She’d show up at the studio at 11:30 pm after having gone to the opera. She had us to her home. She owned a Chagall. I mean, God … I’d never met anyone like that.

Where or to whom do you go when you want honest feedback about what you’re making?

My daughter [Brooke Marks Swanson]. I was fortunate, when I was teaching, one of my colleagues was my best friend, and we’d critique each other. He was honest. And, my husband — he has a degree, too [in graphic design].

What role does exhibiting play in your practice?

When I began teaching, and my daughter was young, I didn’t feel like I had the time to give a piece my full attention. But when she was about 10, I entered a show in a Midwest Museum of American Art show, and they had a juried regional annually. I’d enter, and almost always got in, but I didn’t win awards. I kept at it, and started winning awards. It felt good. It gave my life validity — i.e. she knows what she’s doing. I enjoyed the process. And I enjoy working thematically. If [a gallery] gives me a theme, a title, an idea, man … I’m off and running. That’s half the problem solved. I know what I have to make. I like being a conceptual artists. When I started working, that [idea] was just beginning, in the ‘60s. I was raised on formalism — all we worried about was craftsmanship. It wasn’t very often we thought how your day was going and could we work it out in some clay? I love the idea of 50 different people use a theme [to direct their making]. How exciting.

How do you feed and nurture your creativity?

We travel quite a bit. And we always go to museums. We plan trips around shows, museums.

What drives your impulse to make?

This sounds trite: I like to keep busy. I just love making things. I wouldn’t matter if someone said, We’re going to take away all your clay. Clay is no longer being made. I would probably go back to collage. Or, I could paint. I love making jewelry. I just like art.

For me, it wasn’t challenging at all. My [students] knew I had a theme — that I wouldn’t ask them to do anything I wouldn’t do myself. I had this marvelous classroom, with this great big counter in the back, and I’d always have something going. Especially in the beginning [of her teaching career], I’d always do the project first. That’s where I made my entries for the juried regionals. One of our banks held a Christmas card contest, I’d make a Christmas card for the competition. I walk every morning with a [former] art teacher. I was working in the back of my classroom, and a principal I didn’t enjoy came in, and I jumped when he got up beside me, and told him I hadn’t heard him. And he said, Oh, a bomb could have gone off here and you wouldn’t have noticed. I looked him right in the eye, and I said, Well, for an art teacher, I think that’s a compliment. I was engaged in what I was doing, and I was making art. There were some art teachers, over time, that never make another art piece after they graduated. I always did. I continued making art throughout my entire career. I always felt like I was an artist who taught.

Cynthia Marks is represented by Sleeping Bear Gallery, Empire, Michigan; and Higher Art Gallery, Traverse City, Michigan.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.