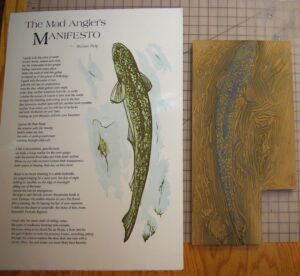

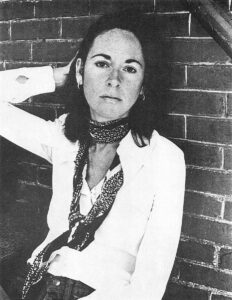

Jan Johnson Doerfer, 73, feels better when she is creating, when she can go down to the beach and watch the water, or connect with the birds, or add to a collection of sticks that are “art waiting to be made.” Creative work has been a constant thread throughout her adult life. Now, this enduring and driving passion is Jan’s primary focus.

This interview was conducted in October 2024 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Jan Johnson Doerfer

Describe the medium in which you work.

I started out primarily painting with watercolor; but then I got into working with pastel. Nowadays, I do some acrylic painting, some watercolor. Plus, I like to work with wood. I’ve got a huge collection of pieces of wood, sticks I’ve collected over the years from various places in the woods, or on the beach, wherever I find them — they are waiting to be made into art.

Is there anything particular about the wood you find in the wild that appeals to you?

I’m very inspired by nature. So, I’m always looking at natural things, whether it be wood, stones, bird feathers. I’m always looking around for interesting items when I’m out walking.

You started with watercolor, and then you began to explore and work in other media. Is there any particular reason why?

I started with watercolor because I love the transparency of it; but I think what happened, over time, was I started exploring other mediums to see what they do. I still love watercolor; but it’s very challenging. You have to put it down and get it right. You can’t erase it, or cover it over — it starts getting muddy. It’s very spontaneous. For that reason, I do like other media that give you a chance to play, to paint over it, adapt it, modify.

Did you receive any formal training in visual art?

I’m interested that you began to ferret out teachers when you needed to learn something. Talk about that.

What’s the expression? When the need arises, the teacher comes. In certain periods of my life, I’ve been very open to the belief that art was really important to me, and I needed to focus on it. At those points, I would seek out — and I can’t remember how I found some of these teachers — and find something that would stimulate me. I do need motivation, and classes are a wonderful way to do that. With classes, you have an assignment. When I’m working on my own, everything else gets in the way: I need to go to the store and get groceries, go out and do something in the garden. That’s something I’ve struggled with all my life. How do you give [your creative practice] the time and importance its due?

In 1981 you began a card shop, and your work was the centerpiece of that business.

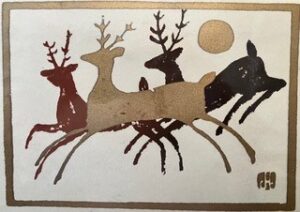

When I was doing the class in Columbus, I became interested in silk screen printing, and asked the instructor where I could learn silk screening. She set up a small seminar with another teacher [who worked in silk screen printing]. And I became very entranced with that. So, I decided I was going to get some silk screen supplies, and I was going to make some cards. I wanted to do something I could sell. I needed to make some money with my art. I was a stay-at-home mom, my husband was working, and I really wanted to do something that would make some money for me. I designed 10 different Christmas card designs … [and printed] 50 cards of each design. This was at the beginning of Autumn. I went to Columbus, to several little galleries and gift shops on the day after Thanksgiving. People laughed at me, and told me they’d bought their Christmas cards in June. But they looked at them, and I ended up selling all of them. I began to figure out how that business works. I started that in 1981. [In 1986, Jan and her family moved to Suttons Bay, and opened a card shop there called Loon Art Designs.] I ended up getting divorced in 1994; but my ex-husband and I kept the business going for two or three years after that. I was ready to move onto other things. The card company grew where I couldn’t do my own silk screening. Eventually I found a sheltered workshop [in Ohio] for people with disabilities. I taught them the whole process. Then a commercial silk screen company that had primarily done logos on hats and shirts for sport teams began producing my cards.

One of the things I find interesting about this story is that size doesn’t matter; you just needed to be making. Because of your life circumstances, you started small, with a card; but you were doing creative work. At the same time, you were learning about the business side of doing creative work. It suggests that developing a practice can start with anything and anywhere.

Creative work extends to so many other things. Cooking is creative. Gardening is creative. Decorating your home is creative. After Loon Art closed in 1985, I started writing. I decided I wanted to write and illustrate children’s books. I wrote a first draft of a young adult novel; but I never got it published. I wrote another book, I See A Bird!, and I self-published it. It started with my granddaughters, one of whom was very interested in birds, and she was only 2. I would make up poems about the birds we were seeing, and recite them to her. I decided to a kids book about birds would be interesting, so I just did it. Birds are one of my passions.

Describe your studio.

It’s a little room that’s the third bedroom in our house. It’s small; but I’ve got it set up just with the stuff I love. At times I wish I had a big studio where you can be really messy with stacks of canvases all over the place; but this works for me.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Birds are a big thing. Water. Natural things, mostly.

You exhibited two works in the GAAC’s Shrines + Altars show that are mixed media, and combine 2D and 3D. How often do your works migrate between 2D and 3D?

Three D[imension] is something that’s fairly new for me to be doing. I love it, and will be doing more of it in the future. I have this collection of sticks, and they’re in the breezeway [of her home]. My husband has asked me, so many times, What are you going to do with all these sticks? Can we get rid of them? No. We can’t. When I did the two pieces [for the Shrines + Altars exhibit], I said, See. This is why I have all these sticks. It’s art waiting to be made.

What’s your favorite tool?

A good paint brush. I love the feel of the right brush in my hand. The whole thing: the weight of it, the bristles, the way it moves paint across the surface.

What tools do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

Nothing fancy. Notebooks. Scraps of paper. Sketchbooks. At times I think why can’t I be organized about keeping this stuff together. I’ll be looking at something, and come upon doodles, or little sketches I made, which I’ve forgotten all about. One thing I use a lot now is Pinterest. When I see something I really love, I have an art folder on Pinterest, and I can save it there.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

When I started the greeting card company. The circumstances were that I was very isolated. I was living in an environment that didn’t feed my soul. I didn’t have any close friends, and I had two little children at home. I really wanted to allow my soul to expand, to be able to do what I needed to do to feel a sense of who I am. Now that I’ve retired, suddenly I have this time I’m free to use for exploring art, and creating. It’s a wonderful thing to have. So much of my life has been filled with other responsibilities. [Jan said that most of her adult work life has been spent with books — in books stores and municipal and school/college libraries.]

How hard has it been throughout the years to create the space and time and space you need to do your practice?

I’ve struggled with my feeling of commitment to taking care of others and being there for them; and what time and space I need for myself. [Both of her husbands] have been very supportive. I’m lucky in that regard. I haven’t had someone saying, What! You didn’t clean the house today! But it’s that inner sense, that I have to take care of the things I have to take care of that is the obstacle for me. As a child, I didn’t grow up in a family, with parents who said, How can we support your artistic inclinations? I wonder what would have happened if they’d said to me, Hey! You want to go take a class at the art institute this summer? I wasn’t the kind to say I want to do this. I was a nice girl. My dad was an electrical engineer, so he wasn’t geared toward art. My mom was a housewife and felt that women weren’t meant to be doing other things. I think: If only I’d had more support; but we have what we have, and manage somehow, and maybe it creates strength.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Very little. When I made the bird book I created a website. I thought I’d do a blog; but it all sort of petered out. I don’t have a social media presence.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s/creative practitioner’s role in the world?

To create beauty, or controversy, or make us think beyond the mere appearance of things. The artist is here to help us expand our vision. To go beyond the norm.

What parts of the world find their way into your work? We know that sticks do.

“Spirituality” is a broad term; but my understanding of spiritually, I want that to be incorporated into my work. Along with nature, of course. Nature is my spirituality. Over time, some of the social issues — climate change, how really horrible the future looks, how we really ought to be paying more attention — I would like to do more with that so that people will think about it a little more.

You lived for a time in Colorado, and that caused you to want to return to the Midwest to live, to be closer to water. How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s hard to narrow it down. Everything about it. The water. The quality of the water. The different colors and textures of it. The way the waves are moving. We live very close to the [Grand Traverse] bay, and I can just walk down to the beach to be able to see what the waves are doing today. and how many rocks have moved onto shore today, and what are the patterns in the sand, and what has washed up on shore. Also, the cloud formations, and the colors of the sunset at times. Driving from [her home] to Glen Arbor, and seeing the trees, and the colors of the leaves, and the hillsides, and the textures of the fields and the trees and the orchards: It’s just wonderful. We live in a really special place.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

The people and teachers I’ve encountered in the various workshops I’ve taken. The painting teacher in Columbus: She opened up my mind, and exposed me to a lot of famous artists, and different types of work, and just being able to talk about other people. I appreciate her mentoring.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

What is the role of exhibiting in your practice?

Not very much. I was thrilled to be part of the GAAC’s Shrines + Altars exhibit. I’m not interested in selling stuff anymore. I like the idea of sharing, and having people see my work. I don’t want to feel a pressure that I have to make something great.

What drives your impulse to make?

It’s innate. I just feel better when I’m creating. If I’m not creating, I get kind of depressed and feel low energy. It enlivens me.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.