Creativity Q+A with Mercedes Bowyer

Mercedes Bowyer, 44, has had a seat on both sides of the arts table. For more than a decade, she lead the Oliver Arts Center, a community arts center in Frankfort, Michigan. After leaving the Oliver, she found herself making the art. A series of life changes pointed her back to an old familiar practice: needlepoint. And in the course of doing it, she discovered a path forward for her inner creative.

This interview was conducted in June 2024 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Mercedes Bowyer

How did you come to needlepoint?

I used to spend my summers with my grandparents down in Florida. As a way to give me something to do so I wouldn’t constantly ask to go to the beach, my grandmother taught me knitting and needlepoint. She prepped a little canvas, and taught me the basic basketweave stitch. For knitting, I think I got as far as knitting a sweater for my Barbie, and that was the last of that. That didn’t stick. I was in middle school, and I did not keep up with the needlepoint. Fast forward to 2020, right before the Pandemic, I decided to quit smoking. Anytime I craved a cigarette I would sit down and work on a jigsaw puzzle, and I did all the puzzles in the house. I found I still needed something to occupy my hands, my time. My grandmother [Jane Moore Black] had made me a work bag, and I still had that [needlepoint] project. I pulled that out, and tried to re-teach myself the basic stitch, and finished that project. That’s how it started. The Pandemic came at a time when I could explore needlepoint further, and I could sit and focus on it.

When you came back to needlepoint, you had an epiphany — that you could create your own canvases, and they would be more satisfying to work on than the ones you could purchase.

As I think about it further, the canvas my grandmother gave me she drew [the imagery] freehand that was very Mondrian. She graduated from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. She had a career in fashion design. She was a very creative person. So, that’s what I came back to: an original piece drawn by my grandmother. It was the middle of the Pandemic, and there are no local needlepoint stores near me. My husband ordered me a small kit. It was a really pretty, abstracted image of a flower. The threads were part of the kit. It didn’t tell you what stitch to use because it was a beginner kit: You were supposed to use one stitch. It was a painted canvas — sort of like paint-by-numbers — so you knew exactly where to sew the blue thread, exactly where to put the yellow thread. Halfway through, where I was supposed to put the white thread, I decided to deviate and use a sparkly white thread. It hit me, before I even finished the piece, I didn’t find it challenging. I didn’t like them telling me where to put the blue thread.

So, I thought, I could do these, but I could do them in my own colors. I could do my own stitch; but why am I spending money on this [pre-fab] painted canvas that some other artist painted if I’m not going to follow their direction, and what they intended for the piece? That’s when I started getting into my own designs. They were very linear, with lots of rows and grids, just trying out new stitches. I was scrolling through social media one day, and saw this pretty image of Sleeping Bear Dunes, and thought that it would be cool if I could recreate that in thread. And, yes: Shame on me. I took the image off of Google. I could not find who owned the image, and I thought that this was going to be just for me. This might not even work. That was the first time I adapted a photo to an original piece. After that, I was so guilt-ridden because I didn’t know who the photographer was, I started to use only my own photos, and my husband’s photos, or photos that I could identify the maker.

At this point, we should clarify that you were still the executive director of the Oliver Art Center. So, you probably had a keen sense of how important it is to credit creative work.

Yes. That’s true. There were many voices in my head going, “Now, now, now.”

When you decided to move from taking someone else’s image and adapting it to your canvas, what was the bridge for you using your original work?

In the early pieces, I tried to do my research and find existing, named needlepoint stitches that would mimic what was in the photograph. So, if I was doing water, I would try to find a stitch that mimicked waves. Since then, a lot of the visual effects I try to achieve, there aren’t existing stitches. Now, more likely, I’m taking an existing stitch, and editing the stitch to fit my needs.

Talk about the imagery you have been migrating toward as you get deeper into your practice.

It started with the Pandemic. We weren’t going anywhere except, maybe, a few drives during the day to get out of the house. A lot of the imagery is hyperlocal: Point Betsie, and the Frankfort lighthouses; and Pierce Stocking Drive — the usual haunts around the area. I did surprise a friend. I stitched her a log cabin, and I really enjoyed the process of [depicting] the architecture, recreating the building, the sidewalk, the log planks. I find myself drawn to buildings, and the built environment that’s nestled in Northern Michigan.

You’re taking you own photographs, and transferring them to the canvas.

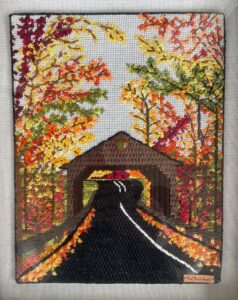

When I got serious about it, I invested in a light box [which enables her to be able to] trace the main elements directly onto the canvas. So, if I’m doing the Pierce Stocking Bridge, I do the outline of the covered bridge, the outline of the road, but the rest of it I fill in from there. It’s not like I’m doing a full, painted canvas like you’d seen in retail stores.

How much latitude do you allow yourself to interpret what may, or may not, be there in the image you’re using?

I give myself quite a bit. I’ll use the Pierce Stocking Bridge as an example. The picture I took was after a rain storm, so you could clearly see that part of the wood on the bridge was wet. I decided to depict the change the colors in the piece from summer to fall.

What made you think needlepoint could be a creative practice?

I was enjoying the process of it. In a way, I was connecting with my grandmother. She needlepointed well into her 90s. I did get a little worried when I was halfway through that painted canvas and realized I didn’t like this. So, I thought, I enjoy the practice of this. I don’t like being told what to do. So, how can I flip this around and make it something I like to do? I was so drawn and connected to the practice that I just needed to find my own way for it to make me happy.

What is the difference between embroidery and needlepoint?

The main difference between needlepoint and embroidery is what the stitches are applied to — usually with needlepoint, it is canvas [not like painters use, though].

Talk about the training you’ve gotten in needlework outside of what your grandmother taught you.

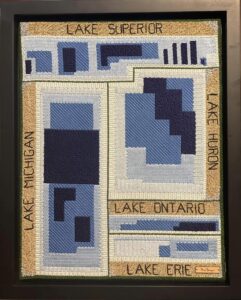

I did complete the American Needlepoint Guild’s Master Needle Artist. It’s a two-year program, and the application was more strenuous than the actual program. I was asked questions about composition, color theory — basics that people would be taught in art school, that I never learned. I had to do some really quick learning in order to answer the questions on the test. Once that test was accepted, I spent a year writing a thesis. And in the second year, I had to do an original composition based on that thesis. It had to go in front of a committee for review. Come September, when they have their annual conference [in Missouri], I’ll receive my certificate and pin.

What was your thesis?

The role of needlework samplers in early American women’s education. It blew my mind as I was doing the research. You’d think that samplers were used to perfect your skills; but the reason you created a sampler and your parents hung it in their living room was so that potential suitors could see that you’d make a good wife.

There was a lot of moralizing expressed in samplers.

Right. A lot of the topics of those samplers were bible verses, statements about social mores of that day. Some of it was education. [The maker] would stitch numbers and the alphabet. Sometimes buildings were incorporated to represent the family home. There are [historic examples of] samplers done by children age 5; but your don’t see much work done past age 14 — at that point, most women were married. They stopped doing needlework for pleasure, and started using needlework to mark their household linens or repair clothing.

How did your training affect your creative practice?

One major takeaway was all the information on color theory: hue, saturation, complementary color. I only use DMC [brand] six-strand floss. Mostly, that’s because it’s the most available in a rural region. You can get it at a fine art store. Heck. I can get it at Walmart. DMC makes thousands of colors. I was working on a piece, and I could not find the right red I wanted: brick red. In doing all the color theory research I did, that’s how I started to mix my thread colors. For example, out of the six strands, I’d pull two out and and put in a different shade of red to get the look I wanted. It was either that, or I was going to have to begin dying my own thread, and I didn’t want to get into that.

Describe your studio/work space.

Primarily where I work is in the living room. I hunted around and found a really cool mid-century sewing table. It sits next to a chair with a really strong light. That where a majority of my current projects live. My home office space is also my work space [where she keeps thread, canvas, and other tools].

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

Currently, my focus is Northern Michigan sites. That’s everything from the State Hospital [now the Village at Grand Traverse Commons] to the Grand Hotel on Mackinaw Island. I like to have a connection to places — my husband can send me all the photos he’s taken; but if I don’t have a connection to it, I don’t feel I have much buy-in, which is another reason I don’t do commissions.

What kind of pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

Typically, once I’ve selected my subject matter, I try to make sure I have multiple images — even if it’s different than the image I’m going to recreate. I prep the canvas — I have to cut it down — and then I usually bind the sides with masking tape because when you cut the canvas it gets sharp, and will snag your threads. I trace the image onto the canvas. And I swear by stretcher bars. I can’t just freehand sew it. I have the full booklet of DMC threads, so I can look at the picture and determine which threads I want to use. Because I live an hour away from the nearest thread store, I have to pre-plan. I’m finishing up a piece right now, and my mind’s already on my next one [thinking about] what colors am I going to need, how am I going to do this — it’s usually one right after another.

What’s your favorite tool?

I have two. One is my stand. I promised myself if I juried into a show I’d entered, I was going to let myself buy this floor stand. It’s about $400. It’s not cheap. But it’s well worth it. I use it with almost every piece I create. It holds the stretcher bars so that my hands are free for stitching. Some of the intricate stitches require two hands. Or, if I’m getting really detailed, I use my second favorite tool, which is a set of dental tools. The hooks and picks the dentist uses, I use to move threads out of the way.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? What tool do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I have blank journal that’s gridded paper, that matches a needlepoint canvas. I subscribe to a few magazines, and if I see and interesting stitch I’ll cut that out and put that in the journal, and make a few notes about how I could use it. If stumble across a stitch I’ve edited, and used in a piece, I’ll record what I did so if I want to duplicate what I did, I have a record of it. I don’t do a lot of lettering, but to work that out on the grid is an important process. My thesis piece I did an abstracted view of the different depths of the Great Lakes. I really had to map out the stitches I was going to use on that one. It was a tight grid. It was worked out well in advance on graph paper.

Let’s talk about the 800 lb. gorilla in the closet. Needlepoint is a creative form that goes back to the Egyptians. Contemporary needlepoint, however, is generally thought of as a hobby activity, sometimes disparagingly.

I attended an opening last week, and a woman was commenting on my work, and she said, “Wouldn’t that look great on a tote bag.” I thought: “It’s not a patch. It’s a piece of art, and you want to sew it on a tote bag?”

How do you talk to people when they say things like that? How have you evolved what you want to say to people?

At first, I didn’t put any thought into it. When I’m entering a show and am asked on the application what the medium is, I put “needlepoint.” That’s what it is. But, then, I was getting a lot of rejections. My husband said, “Do you think people think you’re stitching a painted [commercially-produced] canvas?” They’re not seeing it as original work, and that set me back a little bit. I just assumed people would know it was original work. Right now, I go back and forth about what I call it. For a long time, I’ve stuck with “fiber art.” Maybe I should re-think this and go back to “original needlepoint.” But when I talk to people about it, in the instance I mentioned, it was in passing, and I kind of nodded, and joked that, for the cost of it, “You can do whatever you want.” That’s why, whenever I get asked to speak about my work, my practice is to just engage in conversation about it. I try to get people to understand that, yes, I use needlepoint canvas and thread; but that’s pretty much where [the similarity between Mercedes’s work and commerically-produced needlepoint projects] ends. Some stitches will appear familiar. Others I’ll make up. And, I think that’s what frustrates some of the forum I’m a member of online. I keep on trying to get into shows, so I can put the work out there, and word’s getting out, and people are understanding that “needlepoint” is one descriptor; but it talks about a wide range of what people are doing.

What role does social media play in your practice?

It should probably play a large role. I have my personal Facebook page, and decided to create an Instagram page where I share all my needlepoint. But then I discovered as I expanded what I was doing into the Master Needle Artist program, and I was doing more talks, the need for a website reared its ugly head. I don’t spend as much time updating my website as I should. Sometimes I’ll do three Instagram posts in a week; sometimes you won’t hear from me for three months. I’ve reached a large audience through Instagram. I tagged this international podcast, and they reached out and we did an interview. I could be using it better; but I also have a day job, and a family, and find sitting down to take an Instagram tutorial akin to pulling out my toenails. I’d rather disappear from social media.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

It’s twofold. What I do, I do for my personal satisfaction, to see if I can do. The piece I’m working on right now is of the Tahquamenon Falls in the Upper Peninsula. I wanted to see if I could replicate the foam in the water at the base of the falls. What drives me is, “I wonder if I can do that, and how well can I do that?” I’m not one of those people who believes they’re putting it out there for the betterment of mankind, or to make the world more beautiful. I’m driven by what I want to see out there.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

Definitely, my grandmother [a fashion designer for a Chicago department store]. She created my paper doll. She hand painted it in my likeness, and created a template for making her clothes. At the same time, my grandfather was an architect. I remember conversations with him — he spent one afternoon talking about keystones, and their role in architecture, and all the different kinds of keystones you’d find in a building. I never really thought about that as a creative practice until I started depicting buildings. One of the other things was my education. I grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and we had a program where we spent six weeks, once a week, going to the Saint Louis Art Museum. We’d be met by a docent, and given a tour of a different branch of the museum, and we would do a project. I vividly remember those projects, and being in that museum. That’s always been around me as I was growing up.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

My grandmother. I saw her [doing needlepoint], and she did it well into her 90s and was very proud of it.

What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

In some aspects, that’s the end game: I want to have a piece for the [Oliver Center’s] annual members show, or the annual fiber show; but I don’t think that dictates what I do: I don’t do a lot of themed shows just because I don’t have anything that fits the theme. I see exhibiting as the endgame when I’m working on a piece: Where can it show? Who can see it? It’s another tool for me to get the work out there. I don’t care about awards. I don’t care if it sells. I don’t do it for that. I do it to try and spread the word that this is art, too.

How do you feed and nurture your creativity?

I do it every day. Just doing the work. I subscribed to a bunch of periodicals when I got started. I wanted to see what was out there, and what other people were doing. I enjoy going to other exhibits and finding other artists [working in needlepoint] and try to connect with them. I’m always on the lookout for fiber shows — whether it’s basketwork or quilting, I’m drawn to it.

What drives your impulse to make?

I’m not sure what does; but I have the impulse daily. Some days I’d really love to call [into work] sick because I’ve hit my stride on one part of the canvas, and I want to see it to the end. And, there are other days it’s the last thing I want to do. The piece I’m working on now, I’m not liking how it’s turning out. Just not happy with it, and want to get it done. I’m not one to do more than one project at a time. If I start one and get tired off it, I just work through the block and get it done. That’s my drive with this one. Overall, I just want to see if I can do it, test myself. The last piece, I did a lot of color mixing. I wanted to mimic sun rise, reflection on water, figures. I’d never done figures before.

You have a day job — as Donor Engagement Director for the Grand Traverse Regional Community Foundation. How do you juggle the demands of working your day job, and your studio practice? How do you make the two talk nicely to one another?

One pays for my ability to do the other. I view my creative practice as my break, my after-work decompression: I don’t come home and have a drink at 5 o’clock; I come home and I stitch. If I’m overwhelmed and not having a great day, I sit down and I stitch. That’s how they work well together. One involves a lot of head space, a lot of people-ing. As an introvert, it’s draining. I’m one of those introverts who can fake it, and be good with people; but it exhausts me. I find that the creative practice recharges me.

Read more about Mercedes here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.