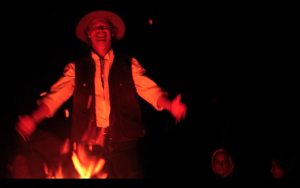

Terry Wooten, 72, is an oral poet, a bard in the truest sense. This Antrim County artist has authored more than 500 published poems, and memorized 567 poems. Until the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, Wooten regularly traveled to work with school children throughout Michigan on an array of poetry and oral history projects. And, every summer for more than three decades, he lit the fire that illuminates Stone Circle [1], an 88-boulder, three-ring circle on his property 10 miles north of Elk Rapids. Before COVID, under the summer stars, anyone who wanted could recite a poem or tell a story at these Saturday evening gatherings. Unlike the petrified stones, poetry is a living thing and a way for Wooten to talk about everything that interests him in the world. And, by the way, April is National Poetry Month. This interview took place in January 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal. GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity.

Describe the medium in which you work.

I’m an oral poet. I’m a performist poet.

Your work seems to be divided into three boxes: Your own writing practice, working with school children, and Stone Circle.

Actually there’s four boxes. I do the column [2] for the Record-Eagle, too. A lot of times I’ll take the prose of my newspaper columns, and after it’s published, maybe a year later, I’ll concentrate it, change it around into a poem. So I use some of those columns for poetry.

Sometimes when I’m working on a poem and I haven’t finished it, or there’s a line I don’t understand what to do with yet, I’ll perform the poem to kids anyway, and will make up something while performing the poem. After I’ve performed it three or four times, I’ll take the one [version] I like best … and that’s what will become the finished product. Also, you get a lot of insights into your poems when you perform them in the schools and Stone Circle. There might be a line the kids don’t understand, or seems vague to people, and I’ll realize I have to touch it up a bit … [Once, while] working in the Traverse City schools, [a sixth grader who] was born on Sept. 11, 1990 and turned 11 on 9/11 [September 11, 2001], told me the story of going to school and waiting for her mom to bring the [birthday] cupcakes … And it didn’t happen. She felt so violated. During my workshop, I teach kids to talk to write. I told her she should talk that and write it, and she did … I came home and wrote a poem in her voice, and sent a copy to the school. The teacher called me a couple days later and said, You’ve got to come back [to East Elementary]. The Record-Eagle has come to interview Jessica, and we want you there …

Describe your writing practice.

Very seldom do I get an idea for a poem writing at my desk. That’s where I write them, but I might be sitting out in the sun behind my garage … My granddaughter, Annie, we have a game she likes to play. She’ll sing a song from Frozen [3] and then I’ll do a poem, and then she competes with herself, jumping. One day she jumped so hard she fell on her butt backward, she got up and sat on the swing, wouldn’t look at me or cry, but turned around and said, I landed so hard my front baby tooth hit my shin. It’s loose. Now I have two teeth I can wiggle. The Tooth Fairy will be coming soon. She doesn’t have the [COVID] virus. No fairies do. I was sitting out behind my garage later that day and I thought what a beautiful insight into a 6-year-old, and how they’re dealing with the virus. Fairies are immortal. And so, I came into the house and wrote it down real quick; if I didn’t, it would disappear.

What draws you to poetry?

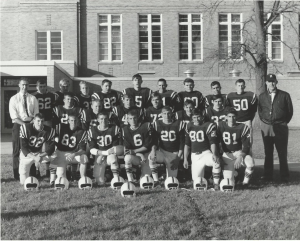

That changes as you grow. When I was a youngster — 8th, 9th grade — there was a controversy in our school about the books Catcher In The Rye [4] and Lord Of the Flies. [5] Both of those books were banned in my school. The same teacher assigned Walden [6] by Henry David Thoreau— she wasn’t even my teacher. She was in the high school. I got a copy of Walden before they banned that, too … and I read the essay “Civil Disobedience,” [7] and it really touched me — that you could disobey civilly against authority. I remember … walking down this main street in Marion, Michigan, my home town, right in front of [Marion] Hardware, thinking, I want to be a writer. I want to disobey. Civilly. [8] That was the beginning, although I procrastinated two or three more years before I really got into it. But I kept it hidden for three or four more years. I started writing about my senior year; but I was a football player, and I didn’t think that football players were supposed to write poetry. One of the messages I give high school kids is: Go ahead. If you’re a football player, write poetry.

Did you receive any formal training?

No. Other than that one teacher who assigned those books. She was a closet beatnik. Didn’t last too long in my hometown. She was too progressive. She opened me up. She insisted you write your own feelings, and I became addicted to that idea. I only lasted two years in college because my family couldn’t afford college for me. After two years, I quit Western [Michigan University], but I had this attic apartment that my boss-friend [rented] to me for $40 [a month]. I used the university library. I went through a heavy Shelley/Keats/Byron [9] phase, and then I remember when Ezra Pound [10] passed, I went up to the library to look Pound up, and was blown away by the Imagists [11] — some of the first poets besides Walt Whitman [12] who didn’t rhyme … I lived in that attic apartment for seven years in Kalamazoo and read voraciously. I was just fascinated by lines. I even keep notes in lines. [13] I’m somewhat dyslexic, so the line structure and the stanza structure makes my poems a lot more accessible for my eyes. I’m writing more now, more than I could memorize.

You immersed yourself up in the attic, and read, read, read.

Yes. It was a nice little apartment. I have fond memories of it. Sometimes I wish I could go back there and stay there for a week.

Describe your present studio workspace.

I have a wood stove. And I built the stone wall behind it. I have three, 4 ft. x 8 ft. bookshelves. I have a window looking out west, and there’s a lot of boulders out there. I’m into visual feng shui. I love the arch of them. Behind that is a white pine forest. I’m constantly watching deer walk by. Squirrels that drive me nuts. There’s a bird feeder. To the left of the wood stove is a big glass door so I can step out. I have three pear trees out there. I’m constantly watching deer, coyotes, porcupines … It’s about 16 ft. x 24 ft. [interior].

It doesn’t sound like your studio space is confined to the four walls of that room. It sounds like the outdoors is as much a part of your work space — at least in your mind.

Yes. I’m an outdoor person. I’m not well suited to be a writer. You’re not going to catch me at my desk all day long unless it’s bad weather in the winter, and I’m transcribing interviews for my Elders Project [14].

What is the work that happens in that studio space?

Very seldom do I do any memorizing in here. Most of my memorizing is done outside when I’m doing odd jobs around the farm or my home or my mother-in-law’s [15]; but once I get the idea for the poem, or a few lines, I work on my computer. I do most of my composing on the computer. I’ve taken to writing a lot of haikus during the pandemic, and usually I write them out on a piece of paper, and type them out.

What is about the pandemic that has prompted a lot of haikus?

They’re healing. A lot of people really like them because you can remember the beginning by the time you get to the end. Sometimes with a 30 or 40 line poem, you have to read it a few times; you have amnesia, and forget as you go down the poem.

They’re healing and uplifting. A lot of people are dealing with a lot of anxiety and depression. Even as I’m writing something that’s serious, I try to keep it upbeat. I love to use humor. Mark Twain [said] that one of the greatest thing we can do about the human situation [is] that we’re here, and we really don’t know why we’re here, and not going to be here someday, and one of the greatest weapons against that is you can throw your head back and laugh.

Does your workspace facilitate your work?

I do a lot of pacing when I’m writing. And this big glass door is nice. You just get up and stare out the window. I can see the Stone Circle from my room. So it gives me room to walk around in.

How is pacing part of your process?

I’m writing when I’m doing that. I’m constantly composing and memorizing. I like to observe people. And before I became really well known, my wife [Wendi] used to get this question: Now, what does your husband do? It doesn’t look like I’m doing anything. I might be standing on the street, listening to people. I hear the human voice like music. Sometimes, something will come out of someone’s mouth, like: Get a job! When I mowed over my wife’s grandmother’s flowers by accident, she said, What’s wrong with you, you’re a poet. Poets are supposed to love flowers, not mow them down. And that, of course, became the idea for a poet: “What’s Wrong With You.”

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

My themes go all over the place. The first few years, when I was young, the theme was myself, my experiences. [Other ideas came out of] the Elders Project. I would bring 8 – 10 elders from the community into the school, and I teach the kids how to interview them, and the kids will listen to the tapes, and take one story and transcribe it. You never know what the elders are going to tell you about … Sometime I run into veterans. There were two teachers in Elk Rapids and they’d both been at Iwo Jima and they didn’t know because they didn’t talk about it … When I was listening to the tape, transcribing it, one of the guys got really shaky. When I found out about this, I called him and asked if I could come over and talk to you about this? It was the beginning of a good friendship. I wrote a whole series of poems on Iwo Jima and his battle experiences. He was on the beaches for five-and-a-half days with what they called a “Beach Party Group.” It wasn’t hot dogs and potato chips. They worked with explosives … He lost his rifle in the first five minutes.

The themes that are the focus of your work could be anything.

Yes. You just don’t know what’s going to come out of someone’s mouth … I got started on the Elders Project by interviewing my wife’s oldest uncle, who was on the Baatan Death March [16]. They were always told not to ask question it. I ended up doing five or six interviews with him, and ended up writing a book called Lifelines. It healed him. He’d never gotten those words out. He’d carried those words around with him for 60 years, and it changed him; but it depressed me …

It sounds like you need to be a very present listener, or you might miss something.

I use tape recorders … I have a friend who produced a film about Stone Circle [17] but he said the first time he met me he had the sense I was very, very aware of the space around me. I guess I am. I hear voices. It doesn’t have to be a World War II veteran who experienced the Baatan Death March. It could be a little girl telling me about how fairies don’t have the virus. All conversation has that potential for a poem.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

When I write my own poems, very little pre-planning. An idea might just come to me, or something will happen that I’ll want to entertain. With Elders Project — a lot; I have to teach the kids how to interview … Then I have to transcribe the recordings. Once I get all the rough prose down I put switch things around … There’s a lot of satisfaction in taking someone else’s story and turning it into a poem of it and giving it back to them. It helps them tell their story. A lot of them can’t write … It’s healing, although it can be dangerous for me.

Do you work on more than one poem at a time?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no.

Visual artists sometimes have more than one thing on their studio wall. When they hit a block, they’ll move over to the other things, and work back and forth.

I don’t do that so much. I have things in a folder, and I’ll pick things out. I go through phases.

What’s your favorite tool?

Pencil and paper and computer. Another one of my tools is my voice. Just saying the poems, and using your ears. I’m efficient with paper [he cuts an 8 ½” X 11” sheet into quarters, and writes notes on a quarter]. I’m just writing down the initial idea, and then I’ll switch to computer.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

I was 18, 19, my freshman year in college. I was already doing things I wasn’t supposed to. I was supposed to be doing my homework, but I was writing a poem instead.

There are two rules at Stone Circle: No swearing, and poems must be recited by memory. Why by memory?

You can swear down at Stone Circle, but I don’t want the big bad swear words. It depends on the audience, too … As far as the memorization, rules are made to be broken. If a little girl or boy would come to Stone Circle with a poem he or she was going to read, and I said you can’t do that, it would cause more damage than good. I do allow some reading, sometimes.

Why is reciting poetry valued at Stone Circle?

You really get to know a poem … when you memorize them. I take a poem on a piece of paper and carry it around in my back pocket and memorize one or two lines a day. As you’re memorizing a poem, you might realize that a word isn’t working right, or you don’t like the rhythm, and I’ll change that …

Memorization has something to do with embedding the poem into your DNA.

For a while you see the words, and after a while you don’t see the words. It’s just there. It’s interesting — you mention the word DNA … I think fire and telling stories is in our DNA. When people come to Stone Circle you can’t sit around the fire and not want to hear stories. It’s there. We’re wired that way.

There’s a lot of competition for people’s attention today. We’ve moved from making our own entertainment to consuming it. How does Stone Circle stand up in the 21st Century?

It’s something about sitting around on those boulders, in a communal atmosphere and listening to those words that sound like songs and seeing the pictures in your imagination — it pulls us back to an early time. What goes on down at Stone Circle could be 40,000 years old. When we captured fire, it expanded our time. And when we expanded our time, we didn’t just curl up when it got dark. We started sharing stories. There wasn’t TV. There wasn’t radio. And with language came stories and poetry. It’s almost like a psychedelic experience: expanded consciousness. I think people, whether they realize it or not, when they’re down to Stone Circle, it’s something really old that touches them. Some people — they’re not so impressed by it. Fire is a very simple tool, but it’s very old. Consciousness and language have grown up together.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Very little. Every now and then I’ll post a poem on Facebook, just to say, Hey! I’m still out there. It’s kind of like frogs singing in a pond. There’s a January poem I post every year, and people have come to expect that. I post my [Record-Eagle] columns.

How did the column come about?

I wrote the editor of the newspaper and told him about my Elders Project, and asked for a column to expose that. That’s how I got started. I own my columns. I can’t give away the copyright to my art.

What do you believe is the writer’s/poet’s role in the world?

Percy Bysshe Shelley said writers are the unacknowleged legislators of the world. I like what Gary Snyder [18] said in his book The Real Work — that we give voice to animals and critters. They don’t have a voice. I can write and give those animals a voice. They have spiritual rights. To me, it’s the poet’s job to give voice to the birds, to the wooly worms, to the frogs — as well as the other people who don’t write and can’t share their stories.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

I write in lower Northern Michigan, so a lot of that appears as a background in my work. I think rural Michigan is my voice. I write in that vernacular, too.

Did you know any practicing poets / writers when you were growing up?

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Two people. Undoubtedly, Max Ellison [19], who recited his poems by memory. I met him Labor Day Weekend in 1980, and had 20 poems memorized by the next weekend. He blew me away. And, Glenn Ruggles, [20] an oral historian who was recording voices and writing down in interviews. There wouldn’t be an Elders Project without Glenn Ruggles …

You’ve incorporated elements of both these people’s work into your own practice: reciting by memory and recording oral histories.

Max — I’d never met anyone who recited poetry like he did, or made a living at it. I’d been writing for 25 years and still struggling, I had a little boy, and working on my wife’s [Antrim County] family farm, but within four years I was making a living as a poet. Unfortunately Max passed. Glenn opened me up to oral histories, or HERstories. It’s not just HIS story; it’s HER story, too …

What was it about connecting with Max that put a booster rocket under your poetry practice?

I just didn’t know you could make a living outside a university. And, because I didn’t have a degree, I was being shunned by university poets. Max had been working in schools for years. When he passed, everybody just picked up on me, and invited me [to teach poetry in schools]. One of the reason I dropped out of college, other than there wasn’t a lot of money, is there was a [required] class [in which] you had to teach people how to write and sing a song and get up in front of an audience. I quit the class, and here years later, I make a living as a professional speaker. Where’d this come from? Max.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

That’s easy: My wife. I get mad at her half the time. Especially my columns. She criticizes them, and at first I’ll be disgusted, but then realize she’s right. Not much with my poetry. Feedback for my poems comes from my audiences. I have an advantage over other poets. I’ve been touring for some 30 years in schools and Stone Circles, conferences, and festival. There’s built-in feedback.

Beside the feedback you receive from audiences, what is the role of the performance in your practice?

It makes the poem come to life. If you do write something down, it’s there. But if you say to them, there’s the power of the oral tradition: You pass them on … Someone asked me once why I broke with tradition by doing my poems orally. I didn’t break with tradition. It’s very old. Chaucer [21] went to Italy and discovered The Decameron tales [22]. He memorized them went back to England and wrote The Canterbury Tales. He couldn’t have done that without the oral tradition. People have passed things down for thousands of years through the oral tradition … There’s a power to the spoken word. I catch that too with my Elders Project. The people say the stories, I transcribe them down into poems, then you turn around and re-memorize them and put them back into the oral tradition. They’re more crystalized. Tightened up. When I teach kids to write, I talk about power words and nerd words. Nerd words are words like: and, really, very, almost, about. Try to get rid of as many of those as possible. Power words are: turtle, trout, belt.

Do the power words hold up better when spoken out loud?

Yes. When you write something like: That’s pretty tough. It’s not “pretty”; it’s tough! We’re sloppy like that when we talk. [When teaching kids] I compare it to making maple syrup. You’re tapping into yourself or you’re tapping into an elder. You’re getting the sap, and you boil it down during the writing process to get the poem …

Will Stone Circle return in 2021 after going on COVID hiatus in 2020?

I hope so. I was at a loss last year. Depends upon the new strains of the virus. I don’t want Stone Circle to end because of the pandemic. We did three or four small [Stone Circle gatherings] last year, but it’s not the same as when you get 100 people. A lot of our audience come from hot spots downstate. You could social distance down there, but at the same time, I blast, I push the words out in the air. It just depends on the pandemic ….. and the red shouldered hawks. If they start nesting down there, it’s going to be a real problem. Two years ago we had some Red Shouldered Hawks build their nest about the Stone Circle wood pile. They’re aggressive birds. I talked to Rebecca Lessard [23], and she said to acclimate yourself to them. Talk to them. Take a radio down there and play it. Recite poetry to them. I still got dive-bombed five times. It’s like being buzzed by a 10 pound hornet … That’s the only times we’ve been closed — for Red Shouldered Hawks and COVID 19. I’m still healthy. I’m a year older than Max when he passed, and that’s a sobering thought, but the fire still burns in me … Not bad for a football player.

Footnotes

1: Read about Stone Circle here.

2: Terry Wooten’s Traverse City Record-Eagle column is Lifelines. It is published the third Sunday of every month in the Northern Living section. He began writing the column in 2010.

3: Frozen is the 2013 animated Disney film based on the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale “The Snow Queen.”

4: Catcher In The Rye is a novel by J. D. Salinger, partially published in serial form in 1945–1946 and as a novel in 1951. It was originally intended for adults but is often read by adolescents for its themes of angst, alienation, and as a critique on superficiality in society.

5: Lord Of The Flies is a 1954 novel by Nobel Prize-winning British author William Golding. The book focuses on a group of British boys stranded on an uninhabited island and their disastrous attempt to govern themselves.

6: Walden is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings. It was first published in 1854.

7: “Civil Disobedience” was published in 1849. In it, Thoreau argues that individuals should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy an individual’s conscience, and that they have a duty to avoid acquiescing to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice.

8: Terry writes: “You’re not supposed to be able to make a living with poetry without working at a university or academy … Being a folk or peoples’ poet was my form of Civil Disobedience. The essay also came in handy when I was resisting the Vietnam War. I was drafted three times, kicked out of Fort Wayne and finally visited by an FBI agent. Turned out my draft board had broken as many laws as I had, and the FBI got me a deferment. Recently I wrote a few poems about my resistance.

9: Percy Bysshe Shelley [1792-1822], John Keats [1795-1821], George Gordon Byron [1788-1824], all English Romantic poets.

10: Ezra Pound [1885-1972] was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II.

11: Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language.

12: Walt Whitman [1819-1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism.

13: Terry writes: “Strong lines of poetry were also something I wanted to emulate. When I was trying to write Lifelines, the story of Jack Miller’s experience of the Bataan Death March and being a POW for the entire war, the story was so gruesome I had to find a more accessible form or eye friendly structure. I started breaking the poems up into stanzas and varying the lengths of the lines. This makes the poems more eye friendly and less intimidating to the reader.”

14: The Elders Project uses oral history interviews to create poetry based on the stories and lives of elders in the community. It was initiated in 2003. In 2013 it won the State History Award in Education from the Historical Society of Michigan.

15: Terry writes: “In 1975 I married into family of [Antrim County] cherry farmers. They also grew peaches and apples. A year later I started working with McLachlan Orchards. It was a big farm, and I spent a lot of time alone trimming trees, picking up rocks and roots, or thinning peaches. It wasn’t all that inspiring unless you had a poem in your pocket that you were memorizing. Early on I memorized a lot of poetry that way. Before long I started working full time performing poetry. My father-in-law and his two brothers have all passed on now, and most of the land has been sold. But there are still two barns and three other building to keep up and grass to mow. I call this “the farm,” but I never really considered myself a farmer. All the boulders for Stone Circle came from my wife’s family farm. I also help my 90-year-old mother-in-law with her house and lawn. I don’t memorize as many poems as I used to, but I have to keep polishing them up, while working on “the farm” or working around my own house. If I don’t they will fade away.”

16: The Bataan Death March was the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of 60,000–80,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war onto trains. The transfer began on April 9, 1942.

17: The Stone Circle, a 2017 documentary written, directed and produced by Patrick Pfister.

18: Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gary Snyder [b. 1930] is known as the “poet laureate of Deep Ecology.” In his 2015 book The Stone Circle Poems, Terry writes: ” Influenced by … Gary Snyder’s vision of a poet in a more primitive sense, a sort of cultural adhesive that helps hold a community together with its stories, I started building my own poetry forum, which I called Stone Circle.” [p. 20]

19: Max Ellison, Bellaire, Michigan bard and the unofficial poet laureate of Northern Michigan, died in 1985. He was 71.

20: Glenn Ruggles taught for 35 years at Walled Lake Central High School. He was a renown oral historian who summered in Grand Traverse County.

21: Geoffrey Chaucer [c. 1340s-1400] was an English poet and author. Widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages, he is best known for The Canterbury Tales.

22: The Decameron is a collection of novellas by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio [1313–1375]. The book contains 100 tales told by a group of seven young women and three young men; they shelter in a secluded villa just outside Florence in order to escape the Black Death.

23: Rebecca Lessard is a Leelanau County raptor rehabilitator and expert. She is the founder of Wings of Wonder, a raptor education center.

Learn more about Terry Wooten here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.