Creativity Q+A with Angela Saxon

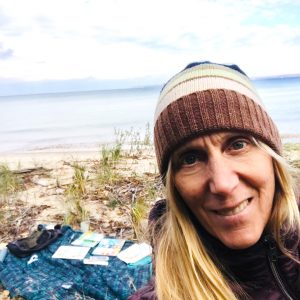

Angela Saxon, 59, is a self-described “mark maker.” That’s her calling and the basis of her creative practice, which is about seeing more, getting beyond the surface of things, and depicting layers of time in her paintings, prints and drawings. The materials she uses don’t define her. She moves fluidly between them, looking for the best combination of tools and processes to interpret the local landscape’s ephemeral essence. Year-round. This interview took place in December 2020. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and was edited for clarity. Angela lives in Leelanau County, Michigan.

Describe the medium in which you work.

I work at making visual things. I currently use acrylic paint, gouache, crayons, pencils and printing ink. That’s for now. I use scissors. That’s not to say it won’t change. I think I’m a mark maker, and that became apparent to me once I started printmaking. If you’d asked me 10 years ago, I would have said I’m an oil painter … But now, I would not say I am an acrylic painter because the media that I use is not as important to me. I’m just always looking for new ways to make marks.

What draws you to the medium in which you work?

I do a lot of plein air [1] work. Currently, gouache [2] is a perfect medium for me for plein air. It dries quickly. It’s water based; I don’t usually have to carry water with me … I paint beside lakes and rivers, so I just dip the water. But gouache, also, you can layer it the same way you can layer acrylic paint. They’re not the same; they have the same properties. I choose gouache because I want to go outside and paint, and I want it all to fit inside my backpack. I choose acrylic [paint] in my studio because it dries fast, it’s non-toxic and I can layer quickly.

You’ve cited layering a couple of time. Explain what that’s about.

The concept of time is increasingly important to me in my paintings. By applying the paint in layers — especially if they’re somewhat transparent layer visible to the viewer — you get a sense of time; not only the time it takes to make the art work, but it also helps me to describe the time of looking, which is a big part of art to me. I spend so much time outside looking, and a lot of the time I don’t even have drawing materials with me. It’s this layered look. I’m not trying to capture the way the camera captures an exact moment in time. I want to capture hours or minutes or years of looking, so layering really adds that element of time into the work. Plus, it’s literally what happens. Sometimes I intentionally put paint on a little bit thinner because I don’t want to hide that underneath layer. There’s a thought [in the underneath layer] that’s an important thought.

You’re a time-lapse painter.

Kind of. It has slowly been revealed to me through my process — I didn’t start with this intention; it has taken me a long time to figure this out … I think I was always jumping ahead to the next thing and the next thing and the next thing. A number of years ago, I had a health situation arise that forced me to slow way down … I didn’t have much energy, so I just went out and sat where I would normally be painting big canvases on location, and I just didn’t have the energy to do it. So, I just started looking. And it was: Dang! This slowing down … Now I feel great, and I can paint in whatever I want. I still spend a lot of time sitting and looking when I go out to work. I realized that was important. That slowing of time. That appreciation of time.

Slowing down is intrinsic to the creative process.

If you go to fast, you run over the idea. You get in front of the idea … If you’re already thinking three steps ahead, you miss [a developing] idea, and then it gets buried. Years ago I looked back at a snap shot of an earlier version of a painting, and I thought, Where’s that painting? I buried that painting. That was a really good idea. I wish I would have stopped there. Artists say that a lot. People ask that question, too: How do you know when to stop on a painting? I think you have to go really slow to know when to stop. My paintings spend a lot of time in process now. I start them, and if I’m not absolutely sure what the next move is, they just have to sit there and wait. It could be weeks.

You have an established reputation as a painter. Describe your migration into printmaking.

The printmaking came about out of curiosity [three years ago]. Anne Corlett, my very close friend who lives in Saugatuck, has a beautiful, big Conrad press [3] that she has had for 30 years. It sat, not used, for the duration of our friendship; I’ve known her for 35 years, and there that press was. I was curious about it. So, I started bugging her about it …… Like crazy people, she and I and [Traverse City painter] Royce Deans did a little bit of research. I figured out what kind of ink to use because I wasn’t using anything toxic at that point. I found this soy-based ink. I ordered the sampler kit, a couple brayers, some Plexiglass plates. We didn’t know what we were doing, but the three of us like to work together … Anne had taken a [printing] class 30 years ago [at the Art Institute of Chicago].

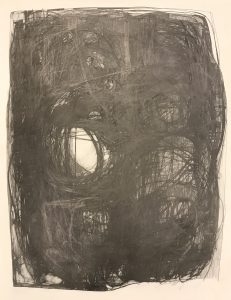

So, it was just curiosity. I always thought why on earth would you make a monotype [4]? Why wouldn’t you just paint? Why would you bother putting the ink on a plate and then transferring it to paper? You only get one [print]. It’s not like we’re doing editions? So, why is it any different than a painting? I think that was the big question I was trying to answer.

How did you answer it?

The answer has to do with time and the visible layers. When you make a monotype, the layers all go down on the plate at once. Then, you pull the print. You don’t know what you’re going to get … When you’re making a painting, you make a mark and then you step back and look at it. You make another mark, and step back and look at it. When you’re making monotypes, especially if you’re doing a one-impression monotype, it’s not as clear what you’re doing when you’re working on that plate. It’s not as easy to see what’s going to happen. There’s something about that mystery, that intrigue — it’s fascinating. And then it prints in reverse. It’s a way to look at your own creative process. Artists use mirrors to look at their work. By looking at your painting in the mirror, sometimes you can see what’s wrong with the composition because you’re looking at it in a way you don’t normally look at it.

How do your decades as a painter come into play in your monoprint-making?

I think that approaching monotype as a painter I’m a little more liberated to try things. Not saying that other printmakers don’t try things. I don’t really know the “rules.” I know how to be a painter, so I approach the monotype in a painterly way … [I] apply the ink like it’s paint, but it’s not paint. There’s been a tremendous impact on [her work] as a result. [ I ] have this whole new language of mark making [to] bring back to the world of canvas.

After you’ve pulled the monoprint, do you ever go back in with paint brush, and paint on top of it? [IMAGE monotype printing]

I don’t. But lots of times I’ll make multiple impressions. That’s one thing that’s different than painting. You can make them a lot faster. In a painting, all those ideas get buried in one painting. When you’re working in monotypes, maybe over the course of a day I might make three or four monotypes of the same idea. I was working on something prescient that foretold my descent into printmaking. I was out painting plein air one day, and I had this idea that maybe what I should do is make four paintings to equal one, as if they were on transparent layers; but they weren’t on transparent layers. They were on four pieces of paper. I put all lights on one piece, all the darks on another, I put the flowers on this one … It was like I was looking into the piece and separating the layers … It was a funny thing. I thought, Gosh. Am I a printmaker?

I don’t think you allow yourself to be confined by any one thing.

I’m not really willing to have a label. When I was in college, I was in a BFA painting program [at Indiana University 1979 – 1983], we were supposed to stay in our discipline, which is really too bad.

How did your formal training affect your development as a creative practitioner?

It forced me to think about developing bodies of work. That might be the single, most important thing I got out of [college]. They didn’t teach me a lot about how to do things. Mostly like: There you are in your studio; make something. And then, defend it. We had to talk about our work. We had rigorous critiques, to defend your body of work … that you’d been making over the semester … [The student would] stand up and talk about it [to an audience of BFA and MFA candidates], and say what you were doing and deal with the barrage of comments and criticisms that came at you. I think it taught me how to talk about work, and to try to think in a focused way about a body of work.

What’s the importance of developing a body of work?

By developing a body of work you get to take an idea or a set of ideas and explore them fully. At the time I was painting interiors of spaces, and I was interested in pattern. So by forcing myself into a size range, using the same medium, using similar subject matter … I think artists can be very excited by what they see, and it’s easy to go from A to Z and back again, and you can end up with a lot of fragmented ideas. In hindsight, I wish I’d learned more practical things. [5] When you’re young and pushed into a place to be a mature artist: good luck. It was hard. It made me so ready to be done with school ….. I was tired of being told what to do. But not really told what to do.

Describe your studio/work space.

It is a separate building adjacent to my house. It’s in a country setting. My husband Erik designed our house and my [400 square foot] studio, so it’s a building designed for this purpose and use. It has a lot of natural light, but not direct light in my painting area. The windows are up high so they don’t shine directly on my canvas. It has tall ceilings in my painting area. And, carefully designed artificial lighting; the light’s really consistent in [her studio].

And, my studio is outside as much as inside. Everything I make originates from my experience outside. All the ideas come from there. All the visuals come from there. I choose to work in my studio so I can approach those ideas in a more meditative, rational manner. I can really tease them apart and see them. When I’m outside, it’s all pretty exciting and emotional. There’s that big response, which is why I work small when I’m outside. The landscape is my studio, for sure.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

My work is really is about the landscape. For the most part. But it’s also about looking. I do work in the figure … It’s a great aspect of my practice, but it’s not a theme I naturally gravitate to.

What is it in the landscape that compels you to paint it?

When I moved here 33 years ago, I never thought I would be a landscape painter. Coming from Chicago, I had a stereotype in mind. I’m still reluctant to say I’m a landscape painter. But when I got here, the landscape overwhelmed me. This is going to sound so cliché – but the scope of [the landscape]: It makes me want to cry a lot. Maybe it’s about my interaction with the landscape. This summer I did a series of paintings about waves … I paddle board, so I’m out on the lake a lot … out on the surface of the lake looking down into the water. I was out on these really big waves and I just stopped [and thought], Maybe I’m just going to look at these waves. Have a little conversation with you guys out here.

You said, when you moved here, you came from Chicago with a stereotype about landscape painting. What was that stereotype?

I think I thought it was not modern enough. Not contemporary enough. Not cutting edge enough. I was young.

How old were you?

I was in my mid-20s. You have ideas when you’re young. You think you know stuff.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

Experiences that are similar to what I was saying about being out on the water. I tend to have an experience, or a series of experiences, but [the inspiration] can surprise me. A couple years ago, Erik and I went to Benton, Tennessee. We were camping. He was busy during the days, so I went off hiking [in the Hiwassee Ocoee State Park] with my backpack and paints. There was this beautiful creek [Gee Creek] tumbling down out of the mountains. I was absolutely overwhelmed, gobsmacked by this creek. I compulsively painted for the week we were there, then came home and made 50 paintings of this creek. I didn’t really want to paint waterfalls or moving water … I cried when we left. I had to say goodbye to the creek.

My current series is of beach grass, and I think it reflects the slowdown of this pandemic. You just have to lie down on the beach and turn your head sideways and just look because there’s nowhere to go. I just started looking carefully, and then I was lost in that world.

How much pre-planning do you do in advance of beginning a new project or composition?

Once I have the idea, I go back to the same places over and over. I’m gathering material. When I come into my studio, I have all this information, and that’s what I work from. If I could work from photographs, that would be awesome; but it doesn’t work.

Why doesn’t it work?

Because I’m capturing this idea of time, and photographs freeze something. Sometimes I shoot little videos on my phone and go back and look at them. The lens makes decisions that are different than your eye can make.

Do you work on more than one project at a time?

I do.

Do you work in a series?

I do, but sometimes little branches pop off the series. I try to stay focused but I also let myself wander a little bit. Right now, I’m working on this beach grass series … but I’m also working on — which seems totally not-related — these very large graphite drawings, which are abstract. The abstract drawings let me spin off my energy. It’s a simplified process. They’re just graphite and paper.

These things all cross-pollinate?

They do. I don’t know exactly how, but it always ends up that they do. I was struggling with creative block for two years. It’s so frustrating. I was working, but it was frustrating, and I couldn’t figure out how to get out of my own way. So I started this series of abstract drawings, 9” x 12” paper, graphite, trying to not doodle, but to work abstractly. It was really hard. I worked through many of them, and started working larger. What was revealed to me in that process was when I took the subject matter out of what I was doing I could feel the real creative me underneath there. And it just opened my paintings right up. I could see again. It was miraculous. It sounds so simple; but it was big. Maybe that’s why I hang onto the graphite drawings. They’re my life boat.

What’s your favorite tool?

I don’t have a favorite tool. I’m interested in mark making, so whatever tool I happen to need. I’ll use anything I have. It depends what mark I want to make. I don’t rule out any possibility. Sometimes I just lay my paintings flat on the ground so I can pour paint and just drag it around.

What tool do you use to make notes and record your thoughts?

I work in pencil on paper. Super simple. I tend to have more than one sketchbook, three or four. I always wish I could be tidy, and have one sketchbook and finish it and get the next one, but I’m absolutely not that person. I just grab whatever’s close.

How do you come up with a title?

Super hard! I try to offer a perspective, an entry point, for the viewer with a title, without being overly emotional or descriptive. There’s also the need for me to have it reference the painting in some way so I can remember it. It’s bad, but when I’m lazy, I’ll say, Wave Series 1, 2, 3, 27, 42 … Titles are a challenge; but when they’re right, it’s so good. I wonder if there’s any artist who says, Oh! I love to title paintings? Sometimes I call my daughter, who’s the English major, and we just talk. She’s great because she doesn’t tell me words; she helps me think about what I’m thinking.

When did you begin working with serious professional intent?

I think I’ve been a professional artist from the time when I was in my 20s. When I was in college, I defined myself as an artist. It wasn’t a hobby. I was approaching it with a very serious intent. I do think that intention really matters. About six years ago, I decided I wanted to do less design work [6] and more painting work. It’s interesting when you say that out loud to yourself. It really started to shift.

What role does social media play in your practice?

Social media [Instagram and Facebook] is a wonderful tool to connect me with other artists all around the world. There are artists whose work I would not know. I think about when I was in college and we relied upon art magazines, and someone else was deciding what art we were going to see — unless you could go to a major city; but, again, a gallery is deciding [what you see]. In that sense, [social media] is great. I love that connection with other artists. And, it’s a great way for me to share what I do.

What influence does social media have on the work you make?

I’m careful about what I post of my own work. I like sharing my ideas, but I do try to be careful not to share them before I’m ready for comment … There are points in the creative process when you’re at a delicate place. You have to be careful who you show something to, or what they say — you can’t un-hear things. It’s a tricky thing, knowing when to share and when not to.

Is this different than getting together with people to do a live critique?

In a way, it’s the same thing … I try not to share during those delicate times because the piece doesn’t have enough substance yet. I want it to be my substance. I don’t want [the work] to be influenced by other people’s comments. Even if they’re positive.

What do you believe is the creative practitioner’s role in the world?

I think we’re interpreters and translators. And, we’re scientists, too. We make something from nothing: There’s not an idea, and then we have an idea, and then we manifest something. And, much like a scientist, we try a million versions until we land on the right “vaccine.” As a visual artist, and specifically, for me as a landscape painter, I like communicating the way that I honestly experience the world, the landscape around me, wherever I am. Artists offer these perspectives that not only make other people’s visual experience richer, but expand visual language, expand visual possibilities for somebody. Maybe they’re sitting at the beach one day looking at the grass and they think about one of my paintings, maybe they’ll look at it differently and see more. And who doesn’t want to see more?

Conversely, what parts of the world find their way into your work?

I don’t believe my work has a political component to it. I come back to the word “beauty.” By acknowledging beauty [in her artwork] does it remind us to seek that balance somehow? [The graphite drawing hanging in her studio] it has layers and layers and layers on graphite on it. I’ve been drawing on that piece of paper for three weeks. And I really think it’s a lot about how we’re connected and not connected right now. A lot of the drawings I’ve been working are super pandemic-related. Another one has all these little shapes — I’ve been thinking about us all in our little pods. It’s a little bit literal for me. In a way, the drawings are exploring some darker ideas.

It can be hard to focus right now. The drawings help me ground and focus my brain in a visual way. I’ve heard a lot of artists in interviews say that, strangely 1.) The pandemic isn’t that different from my normal life. This is what I do: I stay isolated in my studio and do my work; and 2.) There are some positives. Some of the pressure has been taken off. You don’t have to paint for shows. No exhibitions to organize. That productivity piece — as in having shows and getting work to galleries — has been backed way off. In a way, it has allowed my mind to expand.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It certainly heightened my awareness of the landscape. It’s spectacularly beautiful all the time, even in the middle of winter. The pace of life here makes it easier to see that beauty, too.

The local landscape is an intrinsic component of your creative work. The local landscape is also influenced by human activity, climate change, commercial interests, and other modern-day impacts. You don’t work in a static, hermetically-sealed “natural” environment, but one that continues to change and be changed. How do you reflect upon that reality?

I feel that anyone who is awake to the world around them sees what is happening to the natural world. Up here, in the supposedly pristine north, it is a bit more hidden. Of course we see the lake change; but it’s not changed so much that we can’t swim in it due to pollution, so it’s harder to feel it personally. I grew up on a very industrial part of the lake in Gary, Indiana. With steel mills surrounding my beach. The water there is very compromised due to pollution, yet the sunsets are brilliant because of that same pollution.

I feel such big emotion when I’m outdoors. That question about politics and art making is very hard to sort. I have strong beliefs about what is right and it doesn’t involve any more degradation of the natural world. Mine is a quieter protest. A reach for awareness. We all need to open our eyes and look more, at everything: ourselves, our impact on the world and on others — right? The more we look the more we see. We say that all the time as artists, to help us learn and refine our craft. Well, everyone needs to look more.

When did you take up residence in Northern Michigan?

1987.

What brought you here?

Erik was working for a sail-making company in Chicago. We had an almost 1-year-old child, and we were living in Chicago and thought that maybe we didn’t want to raise a family in the heart of the city. I’ve been a sailor all of my life, and sailed on Lake Michigan. So, we knew this area because we’d sailed on the water all around it. A lot. I’m very connected to Lake Michigan emotionally, and would find it hard to live away from it.

What was your sense, when you moved here, of the creative atmosphere and community in Northern Michigan?

It took me a while to find the artists up here … The Traverse Area Arts Council [7] was where I landed. And, through that organization, I found my peeps. I did not know anything about Traverse City. I don’t know why I agreed to move here. Eric said, You want to move to Traverse City? and I said, Where? Erik and I used to deliver sailboats. We’d sail the Mackinaw race [8] and get paid to drive [sailboats] back to Chicago in the summer. He said, You know, it’s that place where we drive by the Holiday Inn? I didn’t do any research. I left my best friend … and all these [Chicago] artists.

What’s your current perception of the creative atmosphere in Northern Michigan?

There are so many brilliant artists who live here. The artists per square mile: It’s got to be a big number. And we all live without the support of a big city up here. You have to be very self-reliant to be an artist up here.

What big-city supports aren’t here?

Opportunities to have big museums, and lots of galleries, and art supply stores. I miss just wandering around the big art supply stores. You get ideas. I found a jar of pink tempera paint on the sale rack when I was living in Chicago, and it launched me into a year-long series — I was painting interiors — and I made so many paintings. There’s more opportunities to sell work. If you live close to a lot of galleries, you get to learn where your work fits in. It’s just a little easier. But you pay the price for living in city. The pace we have up here is much more conducive to the creative process. I think. I have great artist friends here. I feel very supported.

Would you be making different work if you didn’t live in Northern Michigan?

I think I’ve come to the understanding that my work reflects my life. If I lived somewhere else, I would be responding to that landscape, to that culture, to that society. Wouldn’t that be a fun idea? I’ve done a lot of do-it-yourself residencies … where I just go [to a different place] with my paints, and make my own paintings for a couple of weeks.

What does transplanting yourself to a new place do for you?

The more we look, the more we see. That’s the part of my brain I’m continually training. If I was someone who was interested in linguistics, the more languages I understood, maybe the more I would understand the subtle nuances between languages. As a practitioner of making visual things ….. Those waterfall paintings? Directly influenced two years later a series of wave paintings I made this summer. And I didn’t realize it until I finished the wave paintings. Oh maybe all those waterfall paintings I did, maybe I learned something there that enabled me to see water in a different way. I never wanted to paint waves. And I still don’t like to paint waves literally. But it’s the feeling of the wave, and I think I got that from the waterfall paintings. It all layers on top of each other.

You work en plein air almost year-round. Do you paint in the winter?

I draw [outside] in the winter a little bit more. I’m not going to go out in a blizzard, but a couple weeks ago, it was a beautiful weekend at the lakeshore. I’ve got my boots and [snow] pants. I’ve got a big sleeping bag that I drag around with me. I flop it on the ground and sit on top of it. I’m out of the wind, and it was great. The light is so different in November and December. The sun is so low. It’s way more dramatic. Whenever it’s all snowy like it is now, the trees jump out and say, Look at me! Look at me! I don’t think I’m going to make paintings of snowy trees. They’re really hard to sell. People aren’t too into seeing winter.

Even though you don’t make paintings about winter, it sounds like the work you make isn’t dictated by your sense of what sells and what does not.

Correct. I also think that it’s just part of the practice of being outside and observing. I’ve realized it’s as important to be outside walking around looking as it is to be sitting drawing, in my studio painting. They’re all part of the same process. So even if I’m just hiking in the winter, I’m observing color, I’m observing pattern, I’m observing texture. It all counts. My cousin, who is also a painter, said to me, What would you do if you lived in California? — because the light doesn’t change very much. And, I hadn’t really thought about that. It’s hard to imagine. The winter up here provides us — winter plus pandemic — with a fallow time to digest. I have a lot more studio time in the winter, which I really like, too. I’m not as compelled to be out in nature for eight hours a day. I can just go for one, or two, or sometimes maybe three [hours].

Did you know any practicing artists when you were growing up?

Yes, but not intimately. My great aunt bought my family a life-time membership to the Art Institute of Chicago. I grew up in Gary [Indiana], so Chicago was right there. I went to the Art Institute all the time — as a kid, with my parents, later in high school. That museum was my early influence. I don’t know why I wanted to be an artist because I truly did not know what an artist was. When I went to college, I had no idea. None. Totally naive.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

It was probably the Chicago Art Institute. My love of various artists has changed over the years.

Where and to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

I have a few close friends … We communicate daily, or every other day. We share pictures. We talk about work in development. We talk about ideas we’re thinking about. There are times you just want to show something [without receiving feedback], but that’s pretty rare. I have a deal [with a critique pod]: OK. You’ll tell me if I’m really going off the rails. I might want to; but you tell me. That’s a really valuable thing. I feel so fortunate.

What’s the role of exhibiting in your practice?

That’s interesting asking that question now. I think exhibitions are really tricky. In one sense, it’s super exciting to have a body of work assembled in one place, and get to look at it all together. It’s fantastic for me and I think for viewers. It’s something I love to do, to go to see an artist’s whole idea, and it’s all there in one place; but the practical aspect of that is challenging. Depending upon where an artist is in their creativity/productivity formula, it can put a lot of pressure on you. Some people work really well under pressure. I tend not to. I like to build a body of work and then see if I can find someone who wants to show it — as opposed to the other way around.

You’re proactive about finding exhibition opportunities.

Yes. Or, I work with a few galleries who watch what I’m doing, and might see a body of work developing, and reach out to me [for a solo show]. That happened to me with the waterfall work. I had two, concurrent shows. And I didn’t sell a thing … But because I had two shows, I forced that series to expand it and keep going. “Hey wait: I need 10 more paintings.” It’s like the toothpaste tube was empty and I kept on stomping on it. But now, a couple years later, some of that work is selling. Exhibitions are expensive to do. The gallery doesn’t pay for your costs to mount the exhibition. Yes, they host it, and they do promotion, but you still have to make all the work, ship it and aaarrrgh … It’s going to be a long time before I do a solo exhibition.

Footnotes

1: Plein air painting is painting outdoors, versus painting in a controlled, indoor environment, e.g. a studio.

2: Gouache is a quick-drying, opaque water media.

3: The Conrad Machine Co. was founded in 1945. It began manufacturing printmaking presses in 1956. It is located in Whitehall, Michigan.

4: Monotype is printmaking process. Monotypes are made by drawing or painting on a smooth, non-absorbent surface. The image is transferred onto a sheet of paper, usually using a printing press. Unlike other printmaking processes, monotypes produce a single print versus multiple editions.

5: “Practical stuff I’d like to have learned in school: What a working artist out in the world actually does (interaction with galleries, patrons, writing grants, applying to shows). More fundamental study (drawing skills, mixing colors, styles of painting). I was accepted into the BFA painting program at the end of my sophomore year and at that point was required to focus specifically into a style to produce a cohesive body of work. ? Why go on to get an MFA? If you want to teach, that would be a good idea. What does it mean to teach? None of that was discussed.”

6: Angela and her husband, Erik, are partners in the Traverse City graphic design firm Saxon Design Inc.

7: The Traverse Area Arts Council was active from the mid-1970s through early 2000.

8: The Chicago Yacht Club Race to Mackinaw is a 333-mile, annual yacht race starting in Lake Michigan off Chicago, Illinois, and ending in Lake Huron off Mackinaw Island, Michigan.

Learn more about Angela Saxon here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.