Creativity Q+A with Lynne Rae Perkins

As part of the GAAC’s Everyday Objects exhibition, we spoke with Leelanau County author + illustrator Lynne Rae Perkins. Lynne, 66, is the author of 14 books for children, including the young adult novel Criss Cross, for which she received the 2006 Newberry Medal for excellence in children’s literature. In May, her 14th was published, a delightful picture book entitled The Museum of Everything. This interview took place in June 2021. It was conducted by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

The Museum of Everything is about the mundane — a rock, a puddle, a bush, a skirt made from a bush. It’s about everyday objects that are of interest to one little girl — the story’s narrator — who thinks they’re all museum-worthy. Talk about this.

I think that in some cases, the objects might start out as everyday objects; but her imagination transforms them into something more transcendent. A Spirea bush is something you might see everyday; but a skirt that looks like a Spirea bush would look pretty spectacular. As with the idea that a rock in a puddle might be a boulder in a pond on an island in a lake, on an island in an ocean. A museum is a place for special objects; but I think a museum is also a place for thoughts. That’s what makes the objects [in the story] rise above the ordinary.

I think that in some cases, the objects might start out as everyday objects; but her imagination transforms them into something more transcendent. A Spirea bush is something you might see everyday; but a skirt that looks like a Spirea bush would look pretty spectacular. As with the idea that a rock in a puddle might be a boulder in a pond on an island in a lake, on an island in an ocean. A museum is a place for special objects; but I think a museum is also a place for thoughts. That’s what makes the objects [in the story] rise above the ordinary.

In 1936 Ralph Waldo Emerson published the essay Nature, and said this: “The invariable mark of wisdom is to see the miraculous in the common.” The common things you’ve singled out in this book all have something a little marvelous inherent to them. Can you talk a little about your interest in common objects?

I think that, for starters, I’ve always been a day dreamer. I learned to read early. My sister taught me to read before I went to school. When I went to school I always finished my work before everyone else, and I had a lot of time to sit and stare at the room and daydream. I would fixate on something. I drew a little picture to illustrate this. Pens used to come with a metal clip that wasn’t part of the pen — so you could put it onto your pocket. I can remember looking at this, and thinking it reminded me of the little craft George Jetson used to ride around in. Looking at it for the longest time and imagining it as a space craft — in a similar way as the book’s narrator looks at objects in her world.

At Christmastime, my family put those electric candlelabras in the windows. There was one in our bedroom that was left on for a while after my sister and I went to bed. And because we had two layers of curtains — there was a sheer layer, and then a thicker one — the light shined up through the curtains, and made this picture on the ceiling that looked like a landscape. I felt like I could see a river with the near shore and the far shore. I liked looking and imagining it was a landscape. I would fall asleep to that.

Looking isn’t always something turning into something else. When I went to art school at Penn State University in the late 1970s, I would spend hours looking at something — a still life or figure — while drawing. I think drawing things in that prolonged and focused way becomes a habit you take with you out into the rest of life.

Museums, by definition, are filled to the rafters with things. But museums keep chaos at bay by organizing their things into manageable bites. Conversely, the world is full of things — but without the benefit of any museum-like organization. It can get overwhelming. Your narrator opens The Museum of Everything with this thought: “When the world gets too big and too loud and too busy, I like to look at little pieces of it, one at a time.” This child is wise.

I think this is something instinctive we do, in a lot of ways, although it might not look like we’re doing it. When somebody’s looking at their phone, or when a child is playing video games, or if people are dancing for hours at a time, or if we’re reading or housecleaning or making art, we’re keeping out a lot of things, and just focusing on this one thing. [The book’s narrator] has her windowsill full of favorite things. I have a windowsill in my studio that has stones and shells — who doesn’t go to the beach and pick up their favorite stones and then find a place for them. Why do we do that?

I think your narrator’s thought is good counsel for young readers — about how to manage an overwhelming world, which is part of being a kid. There’s a lot of stuff coming at you.

That’s true. I was telling a friend, when I’d come up with that line for the beginning of the book, she said that I was giving kids a tool. I hadn’t thought about it that way.

The museum that your narrator talks about has many different locations, and not all of them are represented by buildings with four walls. Tell us about one of these: the Sky Museum.

This part of the book started with an idea I had years ago. Many of us have had the experience of flying in a plane on a cloudy day — when you rise above the clouds, and all of a sudden everything is sun lit and beautiful and golden. I remember having the thought that it was like a page of a book you could turn over. At the time I did this scribbly sketch of what the other pages of the book would be — I was a printmaking student so I made a lithograph that was really unsatisfactory; but I kept it because I liked the idea. I wanted to visit that idea again, and do it better. So I started trying to do that. I think that’s where the idea of the Sky Museum came from. It was tricky. I had to make the book shape, which is many pieces of foam core board cut in the curvy shape of an open book. Then, I used wool to make the clouds. Then for the fleecy, lacy page … I used interfacing, from the fabric store, with little pieces of fleece laid onto it. The blue page is paper, and then the next page is velvet with little rhinestones on it, and then there are lights.

The illustrations in this book aren’t just paintings and drawings. You’ve given the story a rich, textual, visual life through sewing, collage, sculpture, and by creating dioramas. How do these media tell the story differently than painted or drawn illustrations?

I got to go to Moscow in 2006, and we went to a National History Museum there. This museum of history went back to ancient times. We were looking at a piece of jewelry that was thousands of years old. Another artist I was with said that the impulse to make something beautiful has been there from the beginning of human life. I think this desire to make something beautiful starts in childhood. My hope is that when someone looks at these things, part of their mind is engaged in wondering how they were made; that makes them connect with the idea behind it, and they connect with it in a different way.

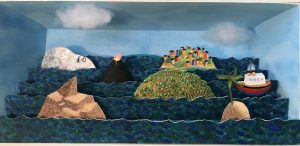

Talk about how you created the island diorama?

Talk about how you created the island diorama?

I can tell you where it started. A few years ago I was a visiting artist on a tiny island off the coast of Massachusetts called Cuttyhunk Island. It’s 3/4 of a mile wide and a mile and a half long. It was an interesting sensation spending a week on an island so small … If you stood on this hump in the middle you could see every edge of the island. When I came home I tried to make a watercolor of the island. I was starting to like how the water was coming out, but the island didn’t feel quite the way I wanted it to, so I decided to embroider the island. I’d been there in November. There weren’t a lot of trees on the island — I think they’d been logged hundreds of years ago — but a lot of bushes and grasses in fall colors. I started embroidering the island — before this book even began.

I’d been on the island as a visiting artist. The 12 year-round residents of the island had had a community read of my book Secret Sisters of the Salty Sea. The students at the school had made dioramas of different scenes in the book, so I decided to make a diorama for my island … I’m not sure how to answer the question about how a diorama tells the story differently. I think they’re just fun to look at.

Inherent to this story is the message about slowing down and looking. We have so many things to look at these days, and not a lot of encouragement to slow down and be still. That seems to be one of the book’s central themes.

That’s true. Sometimes, when I watch a Disney or a Pixar movie, I think they’re so marvelous — why would anybody, why would any child choose to look at a book instead of these amazing movie? And yet, I think there’s something absolutely vital about slowing down, about being quiet, about making things and going deeper. I don’t find it boring at all. One of the premises of making books is if you feel something, other people will feel it also. Making this book is an act of faith. That kids will respond to that sensation.

Learn more about Lynne Rae Perkins here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curated Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibition. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.

The Everyday Objects exhibition runs through October 28, 2021. Read more here.