Creativity Q+A with Matt Schlomer

Matt Schlomer, 51, is finishing his 11th year of teaching at Interlochen Academy of Art. He is a conductor, and he is a teacher of saxophone — and, he is the founder of Sound Garden, an out-of-the-box approach to bringing musical performance to people wherever they happen to be. It’s a way of planting musical seeds in unexpected dirt.

This interview was conducted in May 2023 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

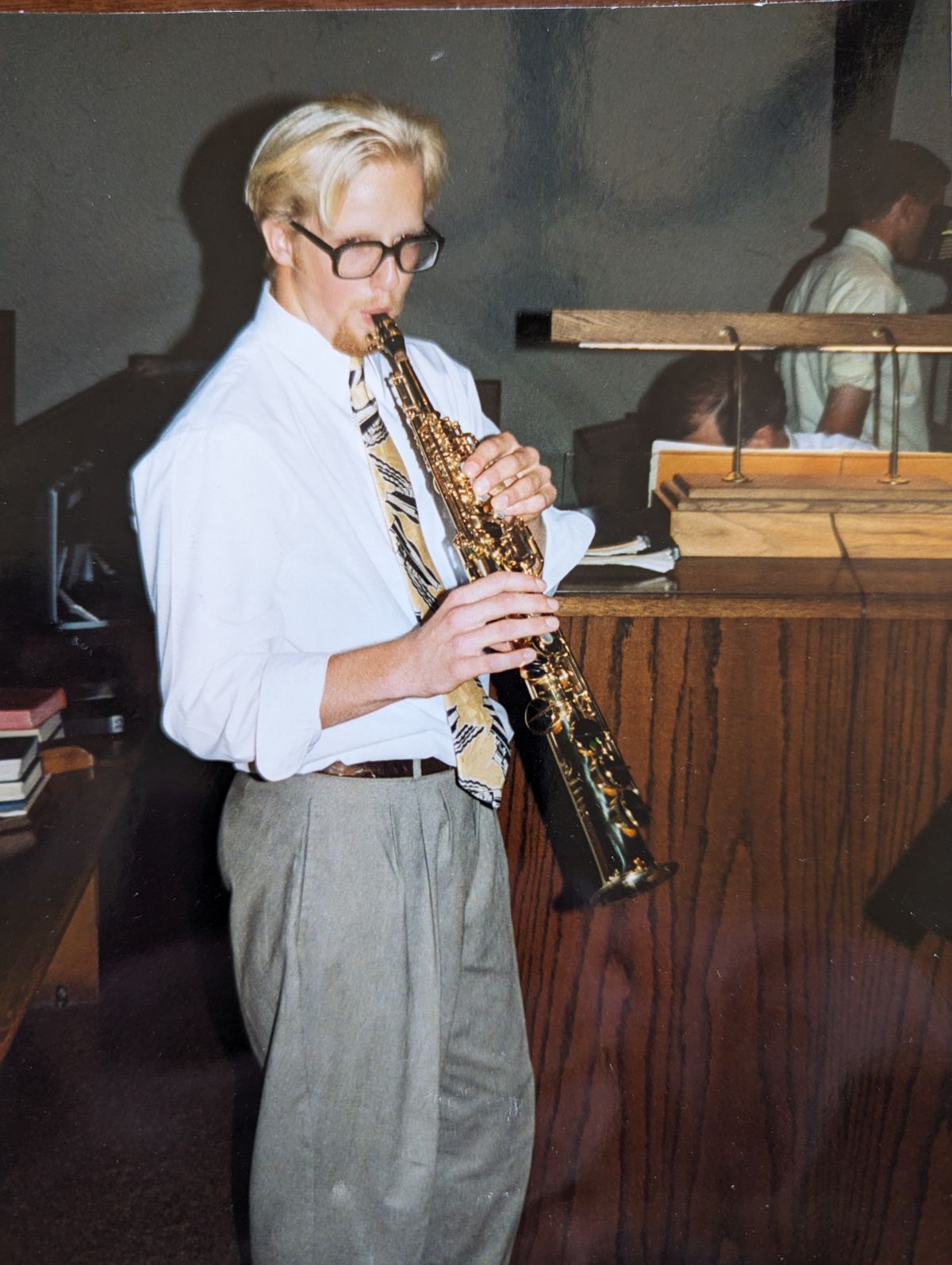

Pictured left: Matt Schlomer circa 1996.

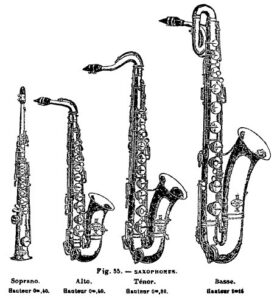

What draws you to the saxophone?

I’m probably 80 or 90 percent a conductor now. My main, musical outlet is one of silence rather than saxophone, even though I still teach saxophone. My thought about silence is that conducting is an odd way to be a musician in that you make no audible sounds. You are physically silent though your inner life is thrumming with musical ideas desperate to get out.

I’m probably 80 or 90 percent a conductor now. My main, musical outlet is one of silence rather than saxophone, even though I still teach saxophone. My thought about silence is that conducting is an odd way to be a musician in that you make no audible sounds. You are physically silent though your inner life is thrumming with musical ideas desperate to get out.

Did you start by playing the saxophone — and that led you to conducting?

Yes. But my mom got me playing piano in third grade.

Because she saw great, musical potential in you?

It was the era when, if you were going to be the all-American family, people had a piano in their living room. Everybody took piano — that was part of the deal.

What did you learn about the saxophone — through your own practice and playing it — that took you by surprise.

What did you learn about the saxophone — through your own practice and playing it — that took you by surprise.

I think what surprised me, looking back, is how it takes you over when you’re playing. It’s so all-encompassing that you almost disappear. As I look back, I think I was more naturally a visual artist. Because the visual arts were easy, I think I didn’t put as much stock in the fact that I could just do it. So, music and the saxophone were this extra challenge that fascinated me, and the pursuit, the trying to tame the thing, overtook the pursuit of the visual arts.

Do the two art forms complement one another?

They do, but in the later part of the pursuit. During what I call the skills-acquisition phase of the evolution of a musician — the high school/college undergraduate [period] — not so much. But when I went to conducting, I [came to] think of it as a sonic painting.

You compose and arrange music. Can you differentiate the two? What creative opportunities do composing and arranging present?

Arranging is more like a coloring book in that you have these outlines, and you have this autonomy to make coloristic choices, but the main form of the work is already done. Composition is more like a blank sheet of paper or canvas where you really have to put your own parameters on it to keep you going in a direction that will turn into something specific. If an idea is borne in your head, you can’t get it out until it’s realized, if it’s there you have to put it out or it haunts you. I’ve found the more ideas haunt you, the more there’s something to them.

You work with large ensembles when you’re conducting. Talk about that.

As a conductor, you don’t have an instrument until you have people to make the sounds. It’s a bizarre dichotomy. Your internal art making has to be overly vivid — the more details you can create in your imagination, the more likely it is you can get them to happen in reality; but in reality, I’m sending out aural images without making any sound. That’s part of the magic. In some bizarre way, there’s some synergy that happens, where it does transfer [from conductor to musicians]. It’s an ironic way to make art.

NOTE: Watch a short video of Matt conducting here.

Are you describing standing before the musicians, and there’s this Martian mind meld between what you’re hearing in your head, and what they’re playing?

Yes. It does sound Jedi mind trick-y, but it’s true and real, and it does happen. The best way to describe it [is to liken it to those] moments when you’re in a gathering, and somebody will enter, and the whole room changes. I do these challenges — we call them “Duels.” I’ll challenge the [musicians], and say, “You have to watch me, and I dare you to play as loud as you can”; or, as soft as they can. I lay down the challenge, and then I’ll overly focus on creating these sounds that are either super quiet or loud, and send this idea of energy and intent. They can’t play it loud. Or, soft. It’s impossible for them to do.

How does your day job cross-pollinate with your own practice?

Music has existed throughout time because of benefactors. In the last 150 years, right now, we’re in the era where music’s greatest benefactor is educational systems. Of course, there are orchestras, and they have their own benefactors. But we’re in a time when there are more full-time musicians, and the reason for that is the education system. For musicians, our personal lives and output, and our paid life all seamlessly mix together. It’s a blurred existence.

If we do creative work, it’s hard to know where it begins and ends. Creativity isn’t some isolated phenomena. It invades other aspects of our entire lives.

It’s my “hobby.” It’s my passion. It’s my career. It’s my way of thinking. There’s a fun mind game we play. If you were stranded on a deserted island, and you didn’t have your instrument, would you still be a musician? That [question] asks you to think about what your relationship to music is.

You have collaborated with a wide range of creative people. What is a collaboration?

It’s a really popular word now. What I would love collaborations to be, but I find rare, is there could be an open dialogue between two creators, and our differences and ideas bang up against each other. We learn a new perspective, and take that opportunity to take that perspective into ourselves and really try to understand it, try to adjust our own perspective until something more complex and beautiful happens. What I often see happening — and sometimes there’s not enough time, or people don’t get to know one another — is people who say, I’m going to put some dance to this, and you’re going to do music, and they call that a “collaboration.” The result rarely becomes a cohesive, powerful, new experience.

In your collaborative projects, people come together, and there’s dialog, and conversation — versus people showing up with their pieces and parts, and saying, A ha! We have a new thing!

And, in my mind, there shouldn’t be an expectation that I show up with my art form — [for example] I’m the musician, so I’m the expert, so you have no right to say anything about it. That’s distasteful to me. There are so many different perspectives. A non-musician can listen to music, and I will learn something about what they hear. Those perspectives inevitably enhance the whole work.

Nobody has the market cornered on a good idea, do they? Why do you do collaborative projects?

In my mind, everybody wins because everybody grows. Everybody has an opportunity to broaden their artist palette by hearing people talk about their own processes. It always feels like a more powerful experience as a result.

Does the Sound Garden Project fall under the collaborative umbrella?

I suppose it’s collaborative in that the big question I’m asking with the project is: How do we interact with audiences in a more authentic way? And interact with people who aren’t looking for us, which classical music hasn’t done.

[NOTE: The Sound Garden Project was founded by Schlomer in 2020 through the support of Interlochen Public Radio. He continues to facilitate the project. Over the last three years, he has put together different groupings of conservatory musicians – from soloists to quintets – who, for two-to-eight weeks in the summer, perform in pop-up and formal concerts at unorthodox, public settings. In 2022 and 2023, the GAAC hosted Sound Garden Project as part of its Manitou Music Series. The PULSE Saxophone Quartet were the GAAC’s Musicians-in-Residents in June. The quartet performed on a pontoon boat in Glen Lake, the GAAC’s Front Porch, Cottage Book Shop, on the Lake Michigan beach, the Glen Arbor Township playground, Glen Lake Community Library, and other places.]

Explain what the Sound Garden project is, and your role in it.

The tag line of the Sound Garden project is: Planting music in unexpected places. The goal of the project is to have an opportunity to hear live performers in a classical music tradition, up close, and experience a sampling of the music so audiences have a first-hand knowledge of what that is like. In practice, we never dummy down the art. What we do is try to meet people in places where they have free time. We try to think where people have time in their lives these days to even have space for something new, and then we try to invade that space, to give people the opportunity to hear that music, and then make sure we create a platform for them to trust their experience.

One of the plagues of classical music is we’ve bred this idea that if you don’t know enough, you won’t get it. I don’t think that’s true. Last year, one of the favorite Sound Garden concerts we did was in [Empire, Michigan] at Grocer’s Daughter Chocolates. They gave us three different samples of chocolate, and we’d approach [customers] and ask them if we could play music for them. They say, Oh, I don’t know classical music. Then we’d say, We have some chocolates for you to sample for free, and then we’ll just play a minute-long piece and ask you a few questions afterward. And, they’d do it. The same people who said they don’t like it, some of them had the strongest answers [about the music and its relationship to the chocolates]. They’d talk about the form of the piece, and the musical elements that made it blossom. There are so many moments like that.

You’re taking classical music out of the context in which most people understand it: a performance space, where you buy a ticket, you find a seat, and you listen. The Sound Garden Project throws all the out the window. With Sound Garden, there is no ticket buying, you go to places where people aren’t there to listen to music, and yet you find ways to have people engage with the music. Why do it?

The tag line — Planting music in unexpected places — insinuates that it’s a seed, and that how anyone’s interest in anything will grow. Sound Garden performances are more like a sampling room. This summer, someone will have their first wine tasting in the Traverse City area. Someone at the winery will tell them how the wine is made. And, from those little samples they’re going to have more interest in wine. Our hope is that people will think what they hear is cool and try some things. One of the barriers we face is the perception that the context in which we play is this high, religious experience where you have to take a large amount of your evening, you have to buy a ticket, you have to go to this hall where you get shut in, and then you sit down and you lose control of what’s happening to you. In this day and age, we don’t do that. That’s an environment, where if you’re going to try something out and you’re not sure if you’re going to like it, you’re already you don’t feel good.

You’re the driving force behind the Sound Garden Project. What was the thing that caused you to think, We’ve got to change the way music is presented to the public.

It’s a lingering question. I’ve wondered about this for a long time, and suddenly there was a canvas to put it on. There’s also a musician side of this. The way that we’re trained does not encourage this kind of thing. We do a detox session with each new [Sound Garden] group that comes into the Sound Garden Project. Not because the conservatories are doing something wrong, but [in the conservatory] there’s a deep-skills acquisition phase, and it’s a crucible of scrutiny. We have musicians who are really accomplished, and people would be thrilled to hear what they could do, but they’re living in this mindset where they think, I’ve got to do all these things, and win competitions before anyone will want to hear me.

Musicians will say, especially with this generation, I want to change the world with my art. But for them to sit down, up close with somebody, to have their instrument in their hand at a gas station or Grocer’s Daughter, to interact with people and give them something meaningful and beautiful that they actually believe in, is such a wildly intimate experience that they’re not prepared to do. They say they want to do it, but they don’t have a context to figure out what that would look like. So, that’s turned out to be a really exciting [part of the Sound Garden Project], and for the musicians. [Sound Garden] gives them a context to put their money where their mouth is, so to speak.

There are some problems from the musician side, too. When musicians come out onto this lit stage, and they can’t see the audience — they’re blinded — and it’s a total atmosphere for judgement from the very beginning. They come out and start playing and supposedly sharing something deep, and they don’t know with whom they’re sharing it. It sanitizes everything. There’s no human element in it. They don’t even meet the audience afterward: They clap. They go off.

What do you believe is the creative practitioner’s role in the world?

I think it’s to help us all to wonder, to keep curiosity alive. I don’t believe that our mission is one of political commentary. There are people who feel motivated, and are rightly informed to do so.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your practice?

It’s just beautiful. I’ve found that an incredible way to re-center. When I’m out in Northern Michigan, I’m able to wonder bigger. When I go for a run in the woods, all of a sudden the ideas are flowing like crazy. What’s magical is there are really great places for us to gather; but then, also places for us to scatter. That’s a special feature.

Did you know anyone when you were growing up who had a serious, creative practice?

I didn’t. South Dakota was a little confining. I was a little bit of an oddity. I was in the art room all the time, so they let me go into the art class in the high school because I was eating everything up. When I was a freshman, and we went to Milwaukee, it was scary. We went from a town of 1,200 to 1.4 million; but it turned out to be perfect. All of a sudden everything opened up. I’m thankful. South Dakota was a safe place to wonder, and to be a kid. And when I needed more stimulation, and to find kindred spirits, that opportunity came when we moved to Milwaukee: concerts, and museums, and Chicago was really close.

Who has had the greatest, and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

I don’t know if there was one person. There’s my conducting mentor, Scott Teeple. There are people like Mary Brennan, she was a professor emerita when I was at the University of Wisconsin getting my minor in dance. She gave me hours of time, where we would discuss the intersection of music and movement, and what I was experiencing, and my questions. It was an incredible gift that she gave to me. I had a philosophy teacher in high school who was amazing — someone with that magic ability to take a teenager who has brain damage, which we all do at that age, and make me feel like he was taking me seriously.

To whom do you go when you want honest feedback about your work?

For a conductor, that’s a rare thing. It’s challenging. I have another mentor, Alan McMurry, who will be honest with me. Scott Teeple will, too; but we’re both right in the busy-ness of our careers, so there’s not much time for there’s not much time for that.

How do you fuel and nurture your creativity?

Exercise. Running. Hiking. Kayaking. The connection between the body, mind and spirit is so true. And the older I get, the more I have to tend to that. You can’t take it for granted. Also, having new experiences. I like to travel. Collaborations help a lot.

What drives your impulse to make music?

With music, it’s about listening. You can’t make as good of a sound by yourself. That act of joining sound is always better if you’re outside of yourself and putting it with the song of others. Getting to do that, and showing that to younger people that that exists is the thing we’re all looking for.

Learn more about Matt Scholmer here. And, here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.