Creativity Q+A with Dani Knoph Davis

“Place has become the bedrock of my work — ‘place’ meaning Michigan, where I was born and raised,” said Boyne City painter Dani Knoph Davis. “Learning about the wildlife of a place is so important, but has been swept under the rug over the last 50 years.” And so, with every brushstroke, Dani, 39, makes work that seeks to raise awareness about the wonder and awe of the other animals who live in her neck of the woods.

This interview was conducted in April 2025 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Dani Knoph Davis

Describe the medium in which you work. What is your work?

I work with watercolor, gouache, pencil, graphite, and heavy cotton watercolor paper to create illustrations of Michigan wildlife.

I’ve often wondered if people who work in illustration feel like they’re not accepted as a part of the Capital “A” Art world.

It is its own thing. I don’t know what happened historically. When you go back to the early 1900s wildlife art was a big deal. Even for my grandparents, wildlife art was a big part of the Art scene. It seemed to slip away.

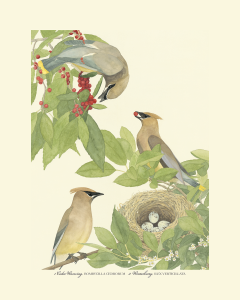

Your work is reminiscent of the style people associate with Audubon. You place your creatures in their indigenous setting, and bring in other critters that might be companions or symbiotic parts of that setting.

Symbiosis is definitely a big part of my work. I find ecology fascinating, how species relate to one another. There’s a deep truth in that. I really crave deep truths nowadays.

What “deep truths” are you craving?

Whenever the world began, life evolved — together, in harmony, in a way things made sense. In society today, I find so much confusion. I think that’s another reason why I create this kind of art: It brings me peace. And, I think other people find peace in nature art as well.

Is the natural world a more straightforward place to you?

Absolutely. One hundred percent. I hate to use the word “escape,” but in today’s world, when I go into nature, I feel like I’m trying to escape society, to find peace.

What draws you to the media in which you work?

In art school they teach you acrylics and oils right off the bat. When I graduated from art school, I found myself living in tiny spaces.To work in oil paint you need windows, and room to breathe and clean up. Watercolor, for me, was more practical. I also fell in love with the process of creating transparent layers — something that’s a lot more challenging with oil paint or acrylic. And it’s a lot easier to clean up.

Where did you attend art school?

I went to the University of Michigan’s School of Art and Design [graduated 2009 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts]. And I did an undergrad study abroad at the Glasgow School of Art [2008]. That was really meaningful.

What in particular did the Glasgow School of Art offer you as a student?

I really enjoyed their program. It was more heavily focused on studio practice. Every student had their own studio space. Then you’d have an instructor you’d meet with once or twice a week, and they’d critique and help guide you. I felt like I started to grow as an artist then; whereas the University of Michigan was more focused on taking classes. There wasn’t enough studio time.

Describe your studio.

It has a view of a lot of trees out the window. It’s elevated on a hillside. I paint during the day, so that natural light is really important. It’s always a little bit messy, especially in the summer, during art fair season. It’s a room in my house, about 14 feet x 14 feet.

Your home studio is a continuation of what you said about working in small spaces. Are you accustomed to that now, or, in your heart of hearts do you long for a warehouse-sized studio?

I would love to double or triple the size of my studio. The next house I buy, it will be a priority to have a larger studio space.

What themes/ideas are the focus of your work?

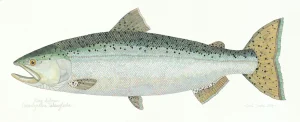

Place has become the bedrock of my work — “place” meaning Michigan, where I was born and raised. Learning about the wildlife of a place is so important, but has been swept under the rug over the last 50 years. We see small groups trying to raise awareness for species, and a lot of them do a great job. Our Department of Natural Resources and local tribes do a great job of stewarding species. But I come at that from an art angle. I want my art to help raise awareness for species in Michigan, but also remind people of the wonder and awe of wildlife. For example: When I’m at an art show, I get two or three good stories from people who walk into my booth, and they see a painting of a particular fish, and that reminds them of fishing with their grandfather; or of a turtle their sister caught when they were younger, and somebody got upset so they had to release it. For some reason, with adults, these things get buried. I want people to remember that these species are out there, and it’s their home, too.

Your work is about direct experience. How do you encounter these animals, and then reinvigorate them in your studio?

All this goes back to my childhood. My family has a generational log cabin on a lake in Gaylord. My favorite memories are being there with my family, paddling around the lake, seeing the loons, painted turtles, large-mouth bass, blue gill. These are experiences that have stuck with me my whole life. There’s always been something inside me that’s told me, These are important things. Don’t forget these things. Remember and share them. After I went to art school and I was trying to figure out what kind of artist I wanted to be, I kept going back to those experiences with wildlife in Northern Michigan. I also come from a family of hunters and fishermen. We have a lot of taxidermy in the cabin. And both of my grandparents were wildlife artists after they retired. To some degree, it feels like carrying on a legacy. I was so impacted by their work. Now, as I grow as an artist, I want to know more about Michigan species that I didn’t know about when I was growing up. It’s my own exploration I want to share with other people.

How do you begin to visualize the animals you want to paint? Are you sitting at the base of a tree waiting for a chipmunk to run over your toes?

No. But that sounds fun. In my earlier work, I’d work from my own photographs. Nowadays, I source inspiration from a program called iNaturalist. It’s a platform for people to take pictures of species and drop-pin their locations. A lot of biologists and naturalists use it in their studies. More recently, I find myself pulling multiple images and collaging them together in Photoshop to create my own compositions, which I paint from there.

What prompts the beginning of a project or composition?

It used to be I would do collections. My first collection was fish. Then I made collections of turtles and butterflies. Now I’m departing from that way of creating art. Trying to be a bit more spontaneous, and more poetic with my work.

What does the poetic part of that mean?

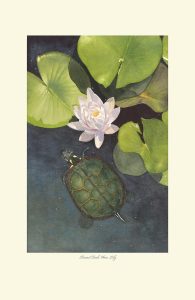

Like this recent piece I did of a painted turtle with a water lily. It feels like a poem to me, without the words. Poetry is another place we can distill and crystalize ideas. Mary Oliver is great at that.

The subject matter you’re dealing with would make it easy to migrate into the totally scientific. In your work, you’re trying to infuse the subject with life. You’re not painting taxidermied work. You’re depicting the life inside the creature.

I try to capture that essence. One thing that has disturbed me about the scientific world of biology, natural history 100 years ago, paintings were always created from death. In biology, you are always looking at the dead specimen in the bottle. I want my paintings to convey the beauty of the life of the creature.

The paintbrush. Brushes and tubes of paint.

Do you use a sketchbook? Work journal? Any kind of tool to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I use Photoshop to create my compositions. But when I have a piece in my mind, I always work compulsively on the composition, and then I go straight into painting the final piece. One and done: I’m not a sketch artist.

Why is making-by-hand important to you?

I honestly feel like it’s genetic, in my DNA. I’ve always loved physical labor, and making things by hand. Given the option of whipping cream with the whisk or a hand mixer, I will use the whisk. I love doing things by hand. I get so much gratification. I feel like I learn more. And, I feel like I’m connected to what I’m doing. I think the way most people can relate to this is: There’s a difference when you type an email versus handwriting a letter to somebody. It’s hard to put words to it, but it’s there, and we all know it. This year I started handwriting letters to one of my best friends who lives in Chicago. It has been really joyful, sharing handwritten letters with somebody.

When did you commit to working with serious intent?

After art school, I moved to Seattle, and felt like Alice in Wonderland throughout my 20s, trying to find a way forward. I felt I needed meaning [in her life], so I started going down to the locks and watching the salmon. I got fascinated by salmon, and learning about their life story. Just the fact that they’re born in a river, and the river imprints on them: After they’re gone out to sea, they know exactly where to return to where they were born. So, I created a collection of salmon paintings, and met with a gallery owner who asked to show them. Weirdly enough, I [in the process of] moving back to Michigan. I got a phone call as I was driving through the Upper Peninsula, and [the Seattle gallerist] told me the whole collection had just sold to a buyer from Oregon. That was the moment I started thinking, OK. I could do this seriously.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I don’t do social media anymore. I stepped away from it in 2019. I found it was giving me more grief than I wanted. I don’t miss it. I haven’t looked back.

Did you step back from it personally and professionally?

Yes.

So, your online presence is through your website.

Yes. And occasionally I’ll send out an e-newsletter.

Many times, in these interviews, artists will tell me how much they value Instagram, for instance. They talk about being able to show the world their work, or being able to look at other people’s work. How do you weigh in on that?

When I hear the word “world,” I cringe a little bit nowadays. Going back to the importance of place, and being in the place you are, and recognizing its importance, I find that it’s more fulfilling for me to be present in the place I am as opposed to scrolling through the world. It’s totally overwhelming for me.

How do you let the world know what you make?

The most important thing I do to connect with others around my work is to do art fairs in the summer. We have a great art fair scene in Northern Michigan. I’ve met so many wonderful people at these shows, and made so many wonderful connections with real people: artists, buyers. People have shared their wildlife stories with me, and that has become cherished and important to me.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

For me, personally: Refocusing our minds on wildlife in the place where we live. And reminding folks of the awe and wonder they’ve experienced in the natural world. At the end of the day, I selfishly want people to care more about wildlife. That’s my drive, even if it’s as simple as not cutting down the tree that blocks your view in the front yard.

It’s an overwhelming job. How do you keep despair at bay?

I pay attention to what our local conservancies are doing, and try to support their work. I try to help share the stories about all the good work our DNR and local tribes are doing — a lot of people like to criticize what those agencies aren’t doing right when in reality they’re doing a lot of innovative work to support populations and habitat for wildlife. I think we don’t give them nearly enough credit. If you go back in Michigan history and look at our state from the late 1800s to the 1920s, the habitat was devastated. Young folks don’t know that now, and a lot of people have forgotten it. Clearcut city: A lot of our woods built Chicago. Overfishing. Sturgeon were almost completely wiped out. If you look back to the 1930s when the DNR was set up, so much incredible work has been done. We can’t take that for granted.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

It’s part of the foundation. It’s the original inspiration for me. It’s an endless inspiration for me. We are so lucky to have so much conserved, preserved land up here.

Would you be doing different work if you did not live in Northern Michigan?

Probably not. I’d be doing wildlife art no matter where I lived.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

Both my grandma and my grandpa, Bill and Joan Davis. When they retired, my grandma painted landscapes in a French Impressionist style. Her painting would make my brain feel like a symphony. My grandfather was woodcarver, and [his subject was] wildlife. We have a loon he carved in our cabin that looks like a real loon. The amount of detail is incredible. They were a huge influence.

Who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on your work and practice?

Laura Yeats. Her partner ran the gallery in Seattle. She was influential, and one of the first people in my early adulthood who encouraged me, and gave me the confidence to take my art seriously.

Where or to whom do you go when you need honest feedback about your work?

My partner, John. I ask him to do this a lot — to look at my work, and make suggestions. In art school, they teach you how to critique work, and it can be brutal, but you learn how to take it and how to word things in a way that is constructive without being offensive. I wish everybody was able to convey constructive criticism. It applies to so many things in life.

Are you able to take those skills and apply them to your own work? Self-criticize?

Yes. I’m very critical of my own work, which is why I spend so much time composing the piece before I put pencil to paper.

You spoke earlier of exhibiting your work at summer art fairs. Let’s get into this some more: What is the role of the exhibition in your practice?

I love sharing my art work at art fairs because you get to meet the viewer, and [hear the viewer’s] perspective, which is something you don’t always get in a traditional gallery setting. I value that so much — on a human level. I’ve gravitated to the art fair world because of that. I’ll do traditional gallery exhibits on occasion, maybe one a year. But it’s so funny to me to drop off a painting, and then see it hung on a gallery wall, and leave it. I love connecting with people over art.

More of that direct experience stuff.

Yes. There’s been this dialogue, culturally, about the lack of third spaces. As a society, we’ve lost these places in the world where anybody can go to, and interact with other people. In Europe, their markets are a great example; or, their civic squares. The library seems like the last-standing example of these places. And, of course, we have great farmers’ markets in Michigan; but there aren’t many places now where you’re just meeting folks, and conversing, and sharing stories. There’s a certain joy and fulfillment of communing with strangers. My mom will help me at art fairs, and she ends up in these conversations with strangers about anything and everything. Next thing you know they’re talking like they’re old buddies.

How do you feed/fuel/nurture your creativity?

It’s always about getting outdoors for me. In particular, the spring, summer and fall. The winter is so quiet up here, but I love finding wildlife tracks in the snow. They [the other animals] are out there even though you don’t see them. I cross-country ski a lot. We’re on the brink of everything coming back to life. I opened the door the other day and heard Spring Peepers. It’s still so cold out, but they’re peeping.

What drives your impulse to make?

It’s like meditation for me. It’s such an intense focus that I can’t think about all the other life stuff that stresses me out.

You have a day job. What is it?

I do marketing, graphic design and some advertising for some realtors.

How does the work of your day job cross-pollinate with your studio practice?

Having a day job forces me to have a really intense schedule. I schedule my studio time every morning. I wake up, and I spend the first three hours of my day in my studio. Then, I do my day job. I run on a strict schedule, and that works for me.

Read more about Dani Knoph Davis here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.